Museums: ticking the trust box

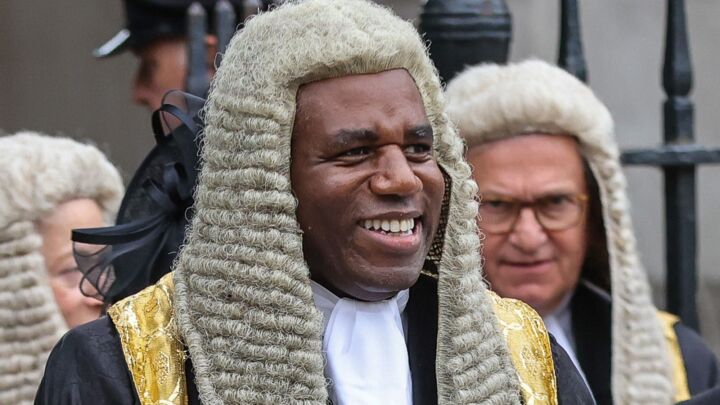

Lord Evans, chairman of the strategic agency for museums and galleries, has attacked culture-by-target. But his alternative is more insidious.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

There was liberationary talk from Lord Evans, chairman of Re:source, the strategic agency for museums and galleries, at the New Statesman Arts Lecture on 27 June 2001 (1).

In the cultural sector, he said, ‘The [government] demand for accountability has spawned a stifling undergrowth of targets, measures and inspection’. His solution? ‘We need to break free from the smothering embrace of this culture of accountability to find a new basis for the relationship between central government and cultural institutions.’

What’s this – a return to the arms-length principle? Are cultural bodies to be given the freedom to allocate funds according to cultural criteria, rather than government priorities?

If only. Evans’ problem with funding by target, it seems, is not that government agendas have no place in culture, but that it is inefficient and ineffective. He cited one Department for Culture, Media and Sport report that named 1,200 indicators of quality in the cultural sector; he lamented all the time wasted by Whitehall staff looking over the shoulders of culture people, and all the time culture people waste form-filling and box-ticking.

If only government could ‘trust’ the cultural sector, said Evans, then there would be no need for these bureaucratic specifications and controls. ‘It is because those at the centre don’t seem to trust people on the ground that we have a proliferation of targets.’

Behind this language of trust lies a more insidious attempt to control the arts – not by force or by prescription, but by persuading people in the cultural sector to internalise the government agenda. Only if they buy into government policy (and really, really mean it), will the cultural sector be given its freedom.

Public bodies need to ‘earn the trust of central government, customers and taxpayers’. Then, and only then, should they ‘be rewarded by gaining greater freedom from detailed interference’ (my emphasis). ‘Self-governance’ comes at a price.

‘We [in the cultural sector] must renew ourselves from within’, said Evans. ‘We…should adopt our own code of corporate governance to show that our boards meet the highest standards set in the private sector.’ Using the John Lewis department store as a guiding example, Evans argued that cultural bodies should devise for themselves suitable pledges and guarantees to make to customers and funders, rather than have them imposed.

And what for those in the cultural sector who think that a museum should not be run like John Lewis? What for those who think that the value of art and artefacts goes deeper than customer figures and satisfaction ratings?

Quite simply, they cannot be trusted.

(1) ‘The Economy of the Imagination’, New Statesman Arts Lecture, 27 June 2001

Read on:

spiked-proposals: Museums and galleries, by Tiffany Jenkins

You’ve read 3 free articles this month.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.