From ‘Hillary hate’ to ‘Hillary hurrahism’

The Clintons did more than most to turn politics into a personality contest. So why is Hillary so shocked to be judged by what she wears and how she cries?

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

As the dust settles from the New Hampshire presidential primary, America’s women voters find themselves in the spotlight. The polls show that female voters made a big impact in the early days of the US presidential primaries. In both the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary, Democratic voters were notably female. A thumping 57 per cent of voters in both Democratic contests were women.

Women not only turned out in record numbers to vote Democrat; their pattern of voting also determined the outcomes of these early contests. In Iowa, women favoured Barack Obama, with 35 per cent of all women voting for him, as opposed to 30 per cent voting for Clinton and 23 per cent for Edwards. Five days later, more women voted for Hillary Clinton (46 per cent to Obama’s 34 per cent), shifting that election decisively in her favour (1).

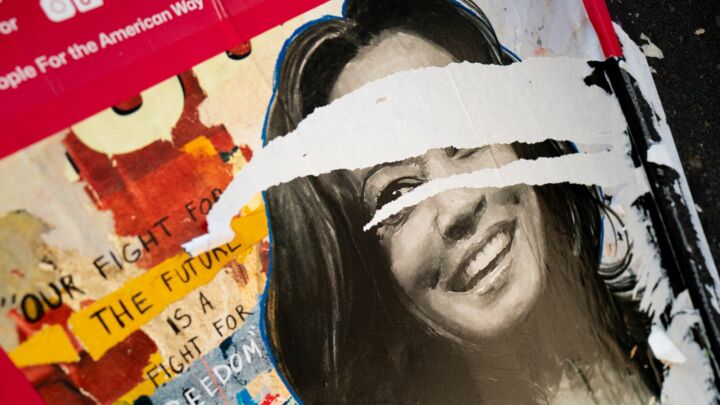

In the week following the New Hampshire vote, speculation was rife as to why women voters ‘came home to Hillary’. For the chat show hosts and others in the media the answer was obvious. It all came down to Clinton’s tears in a coffee shop the day before the vote. The now famed 90 seconds of video, where Hillary is asked ‘How do you do it?’, is credited with transforming the contest. The story goes that those teary eyes and her faltering voice suddenly made women realise that Clinton was not an ice maiden after all, but a warm woman with the same emotions as the rest of us (2). The next day, women came out in droves to support her.

Hillary Clinton’s ‘teary’ moment

It is an endearing explanation. Even Clinton lent credibility to the notion when she said in her victory speech that she ‘found her voice’ in New Hampshire. The trouble is, American women are not that silly. Clearly, if the polls are to be believed, something did happen in the closing days of the New Hampshire primary. All the polls predicted that Hillary would be toast. And a large number of voters – 38 per cent in the Democratic primary – did apparently pick their candidate in the last days and hours of the campaign. But the notion that women suddenly saw a new Hillary Clinton after 90 seconds of video footage in a coffee shop does not really fit with what is happening in this campaign.

Voters, especially women voters, are very familiar with Hillary Clinton. Talking to women about this election, I have found that many women have already thought long and hard about how they feel about her as a candidate and as a woman with a genuine chance of becoming president. Women are paying attention in this election probably in part due to her candidacy. But that said, women relate to Clinton’s candidacy in a more complex manner than many in the press imagine. Some women do support her ‘as a woman’, but many more express a sense of guilt and almost shame that they do not support or like her as much as they feel they ought to.

The sense of guilt that many women associate with Clinton’s candidacy is novel. Normally, if voters do not like a candidate, they find an alternative candidate or resign themselves to voting for them as the lesser of two evils. But with the Clinton candidacy, there is a sense that her candidacy ought at least to be more significant, more historic, even if in reality it fails to inspire.

Such angst springs from the fact that America is a very feminised place. Popular culture is permeated with a sense of female solidarity. Female camaraderie is not a particularly political sentiment. It is certainly unrecognisable from the old-fashioned feminist notions of ‘sisterhood’ – something that was always more imaginary than real – of women uniting in a struggle for women’s rights and emancipation. Today’s sentiment is vague and hard to put a finger on but we all know it when we see it. It is about empathy and encouragement rather than emancipation. It is widely accepted, even taken for granted, by everyone everywhere. And it is a sentiment that exists across the political spectrum. From Oprah to the Disney Channel, from the pop charts to Hollywood, ‘girl power’ is very much part of the norm.

In the days leading up to the New Hampshire primary vote, the Democratic race shifted significantly. After Obama’s victory in Iowa, Hillary Clinton, the assumed Democrat frontrunner, was stopped dead in her tracks. Up to this point, Clinton had been able to assume the mantle of the anointed successor. In all the debates, and in her dealings with the press, she feigned to be above the fray and let the also-rans squabble among themselves. Then suddenly, she found herself as the underdog. Not only was she just another Democratic candidate, she was in fact grappling for her political survival. A defeat in New Hampshire would have meant the total derailment of the Clinton campaign for presidency.

Clinton herself did very little to stop the haemorrhaging of her support in New Hampshire. She was competent in the Saturday debate but her fumbling attempts to portray Obama as a hopeless idealist and herself as the one who could turn words into action were awkward to say the least. And her unfavourable comparison of the civil rights icon Martin Luther King with President Lyndon B Johnson was politically inane.

But while Hillary struggled to find a convincing voice, something else did start to work in her favour. As her efforts failed, the pack mentality of the media began to kick in. Clinton was fair game and the criticism of her campaign let rip: she was too aloof, too unfeeling, too distant. She was asked in the Saturday debate why people do not like her and she was visibly hurt by the question. When she lost her poise in the now famous coffee shop incident, the same 90-second loop of video was played over and over again on every news outlet from dawn ’til dusk. Every moment of it was scrutinised. Did she actually shed a tear? Was it pre-planned? Was it fake? Then she was heckled at one of her final rallies by shock jocks screaming ‘iron my shirts’.

The ‘iron my shirts’ heckler in New Hampshire

Not for the first time, Clinton insiders charged the media with conducting a ‘Hillary hate’ campaign – criticising her in a far more personal and offensive manner than they would treat a male politician. Clinton does have her detractors, but the Clinton camp is rich to criticise the press for the manner of their attack. The Clintonites have done more than most to downplay the role of politics in recent years. Bill Clinton himself was the president who made empathy and personality his trump card. And when his wife characterises Obama as the ‘dreamer’ and herself as the ‘doer’, she herself reduces the contest to a clash of character and personality.

In that respect, the press is simply following Clinton’s lead. When the election is reduced to how people present themselves and their character, rather than their policies, then it is no shock that the media judges them on whether they cry, how they speak, how womanly or how black they are. The so-called hate campaign against Clinton is the logical response to the politics of personality that dominate this contest.

The net effect of this almost self-induced media onslaught against Hillary was that in the days and hours before the New Hampshire vote, Clinton appeared vulnerable and more than a little put-upon. Ironically for all her complaints about the ‘hate campaign’ against her, it was probably this rather than her tears that shifted her fortunes in New Hampshire. It is not that women suddenly saw a new side of Hillary. It was rather that some women in New Hampshire decided they had seen enough.

A young colleague in my own newsroom in Washington DC summed up the mood of the moment. In her early twenties, she is not a Clinton supporter and for all I know she may never consider voting for her again. But when she played me the audio of the heckler shouting ‘iron my shirts’, she turned to me and said: ‘When I heard that I thought “You go, girl” and had I been in New Hampshire I would have gone out and cast my vote for her.’ If the media are carrying out a campaign of ‘Hillary hate’, then the reaction against that campaign might be described as ‘Hillary hurrahism’ – a cheering of Hillary the victim rather than a groundswell of robust support for her political outlook. Both of these responses from Hillary are, in many ways, of her own making.

For those of us who have been around a bit, Hillary’s comeback in New Hampshire should not have come as such a shock. Hillary has been here before. At the height of her husband’s scandal with White House intern Monica Lewinsky, Mrs Clinton also looked more than a little vulnerable and more than a little put-upon. At that moment, her popularity among women shot through the roof. Women felt sorry for her and they weren’t going to kick her when she was down. Once the race was about Obama’s ascendency and Clinton’s collapse, it became a two-horse race and many of John Edwards’ supporters chose to pick sides.

Probably that nagging guilt coupled with a healthy disdain for the media saved the day for Clinton. Certainly a large number of women voted for Hillary this time around. But it is not the kind of support that can be relied upon in the future. Women will probably continue to play a significant part in shaping the outcome of the Democratic primaries, but there is no certainty that they will continue to back Clinton in such large numbers. In such apolitical times, women will be fickle voters. Contempt for the media, a bit of sympathy and guilt-tinged female solidarity will not necessarily translate into lasting or robust support in future fights.

Helen Searls is a writer based in Washington, DC.

Mick Hume asked what Hope for real Change in America?. Sean Collins got to grips with Obama-mania. John Browne looked at why an outsider like Mike Huckabee could win the Republican race in Iowa. Daniel Ben-Ami believed cynicism has replaced genuine political debate. Or read more at spiked issues USA and White House 2008.

(1) Exit polls, MSNBC

(2) Hillary Clinton tears up during campaign stop, YouTube

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.