Voting for Obama: a badge of superiority?

Some of the celebration of Obama’s victory suggests America has entered an era of racial etiquette more than racial equality.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Today, the front page of the British tabloid the Daily Mirror has a photograph of Obama above the headline: ‘The Day The World Really Changed.’ It is testament to the overuse, even the exhaustion, of the phrase ‘the day the world changed’ when the word ‘really’ has to be added for extra emphasis. In our era of historical incontinence, when everything from bloody terrorist attacks to financial crises is treated as an epoch-defining event after which nothing will be the same, we struggle to find the right language to describe things that appear truly historic. It makes you wonder what the newspaper headlines will be if there’s ever another world war or a people’s revolution: ‘The Day The World Really, Really Changed, I Mean Seriously.’

Of course, the thing that appears historic to us today – the election of a black man to the White House – is significant and should not be underestimated. You would need to have a heart of stone not to be moved by the story of the 106-year-old black woman, Ann Nixon Cooper, who was born at a time when black people and women could not vote yet who this week cast her ballot for Obama; or the sight of Jesse Jackson, former acquaintance of Martin Luther King, shedding a tear as he listened to Obama’s victory speech. Obama’s election shows that much has changed for the better in the US. At the same time, however, it strikes me that Obama’s victory, and the way it is being celebrated as historic in public debate, shows that America has entered an era of racial etiquette more than of racial equality.

The key part of Martin Luther King’s speech in Washington in 1963, when more than 300,000 blacks and whites marched on DC ‘for jobs and freedom’, was his description of a future in which black people ‘will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character’. It was a clear, eloquent argument against racism. Yet today, Obama is judged both by the content of his character (in lieu of any clear political programme, he is championed for being charismatic, warm, well-spoken) and by the colour of his skin. Indeed, some white liberal commentators have openly said that part of the reason why they voted for Obama is because he is black – which seems to me the very opposite, or at least a serious warping over time, of what King and others in American history tried to achieve.

The irony of Obama standing on a post-racial ticket, and trying to avoid playing the ‘race card’, is that many of his supporters – especially, though not exclusively, well-to-do white opinion-formers – have said that actually his race is key. Salon, the influential online magazine, published an article titled ‘It’s OK to vote for Obama because he’s black’, arguing that for many white voters ‘Obama’s blackness is his indispensable asset’. It encouraged voters to embrace the fact that voting for Obama is at least in part a ‘symbolic gesture’ and might also feel ‘racially redemptive’ (1).

In the Guardian, white American journalist Michael Tomasky declared in the run-up to the election that, while it’s not ‘politically correct to say so’, many ‘African-Americans and white liberals [believe that Obama’s race] is a positive factor’. Tomasky said ‘the fact that Obama could become the first black president is one of the things we very much like about the man’. He argued: ‘[T]he fact that Obama is a black man is an important factor… There is no earthly reason that it should not be.’ (2) Others argued that white liberals should enjoy the fact that the Obama bandwagon became a ‘cult of racial healing, of racial transcendence’, where ‘for many whites, voting for Obama is a kind of appeal to one’s better self, and the better self of the country’ (3).

Even when the positive endorsements of Obama’s race have not been so explicitly stated (Tomasky advises white liberals to ‘keep between ourselves’ the pro-race argument for supporting Obama), post-election public debate has been shot through with both spoken and unspoken judgements about who is prepared to ‘vote black’ and who is not. The frequently hyperbolic descriptions of Obama’s victory as ‘staggering, indescribable’ (4) suggest that observers are trying to outdo each other in publicly displaying their sophisticated acceptance of the idea of a black president. (Ian Buruma has noted an element of snobbery in European Obamamania, where Europeans seem to ‘feel superior to Americans’ and ‘pat themselves on the back for their lack of racial prejudice’.) At the same time, those who ‘failed’ (in a democracy, surely it should be ‘refused’?) to vote for Obama are looked upon as somehow problematic, possibly even racist. The Guardian refers to them as ‘old white men who don’t believe an African-American could do the job [of president]’ (5). Imperceptibly, implicitly, the question of whether one is prepared to vote for a black man has become an issue of acceptable behaviour and morality.

Not surprisingly, some black commentators have reacted against what Salon positively described as ‘the race-driven enthusiasm for Obama’ (6). Some blacks instinctively recognise that there is little progressive in white people voting for Obama as a way of ‘appealing to one’s better self’. In a scintillating assault on guilt-ridden white liberals, the mixed-race commentator David Ehrenstein argued last year that Obama had been turned into a ‘Magic Negro’ (the name for those black characters in fiction and films who simply ‘appear one day to help the white protagonist’), whose role had become to ‘assuage white guilt’ and to become for white liberals a force of ‘curative black benevolence’ (7).

However, this is not really about ‘white guilt’ in the old-fashioned sense; if it was, we might expect liberal commentators to feel shamefaced, and to really ‘keep between themselves’ their pro-race voting habits rather than advertising them in newspaper columns and in TV debates. Rather, while millions of Americans will have voted for Obama for a vast array of reasons, the celebration of Obama’s blackness by the cultural elite, whether it is done explicitly or implicitly, shows the extent to which race has become an issue of etiquette; how, in a different way to the past, race is still bound up with questions of morality and decency; and most importantly, how having supposedly sophisticated views on race is now, ironically, worn as a badge of superiority over the ‘lower classes’ whose views are markedly less sophisticated.

In America and elsewhere in the West, the issue of race and racism has changed dramatically over the past 50 years. One of the most important developments has been the shift from understanding racism as an idea, an ideological belief and practice of the elite, to viewing it as an all-pervasive problem of ‘wrong attitudes’ and ‘wrong forms of speech’ amongst the public in general. This can be seen in the subtle but important shift, around the mid-twentieth century, from discussions about race to discussions about ‘race relations’; from the ideological view of race as a scientific category distinguishing one group of people from another, to the notion that the relations between races had to be managed, ideally by a supposedly enlightened elite. As Frank Furedi argued in The Silent War: Imperialism and the Changing Perception of Race, this shift sprung from the discrediting of the elite ideology of race around the period of the Second World War: ‘In the postwar period, there was a gradual shift from the focus on race consciousness to one that portrayed racism as a problem for which everyone bore responsibility. The logic of this representation was at once to implicate everyone and no one in particular.’ In the 1950s, this transformation of the issue of race was ‘systematically developed into a powerful theory of race relations’, says Furedi (8).

This historic turn, where the question of race changes yet race remains a major issue in public debate, has had a detrimental impact on trust and relations in society. In their perceptive book, Black Anxiety, White Guilt and the Politics of Status Frustration, the American authors T Alexander Smith and Lenahan O’Connell explore the impact that the ‘personalisation’ of the race issue has had on contemporary morality and debate. They argue that racism has in recent decades been ‘redefined as a state of mind’, so that ‘no longer is a racist merely the individual who denies another individual his or her fundamental or contractual rights in the social, economic and legal realms of daily existence’, but rather is the individual who ‘harbours certain thoughts that express themselves in unintentional assumptions, gestures, attitudes or behaviours that are felt to threaten the self-respect of a member of another race’ (9).

In such circumstances, argue Smith and O’Connell, racism becomes less about the top-down denial of ‘legal rights’ to blacks and more about the ‘moral failure’ on the part of individuals to behave and speak in the correct fashion; this has given rise to what they refer to as an all-powerful ‘Sensitivity Imperative’, the self-policing of one’s speech and behaviour, which can seriously harm interpersonal relations and public debate (10). Indeed, in her book Race Experts: How Racial Etiquette, Sensitivity Training and New Age Therapy Hijacked the Civil Rights Revolution, Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn explores the external policing, too – in workplaces, on campus, in public life – of individuals’ attitudes to ‘other races’ (11). Thus, the issue of race has become one of etiquette, of behaving in the acceptable way, of distancing oneself from the ‘moral failure’ of backward attitudes by making a contrived display of elite sophistication in all matters racial. As Smith and O’Connell put it, in recent years we have seen the rise of a ‘race etiquette’ where ‘racially attuned whites’ have developed keen ‘intellectual, moral and linguistic skills for sending appropriate signals of sensitivity’ (12).

This is what underpins much of the cultural elite’s pro-Obama, pro-black sentiment: it is less a commitment to true equality, certainly of the character-over-colour variety promoted by King and others, and more a public performance of moral sentience and goodness. It is the exercising of good etiquette, and crucially a way of distancing oneself from those parts of America – ‘old white men’, ‘rednecks’, the ‘bitter brigade’ – whose refusal to endorse Obama is re-presented as a moral failure in racial etiquette terms. It really is, as Salon put it, an ‘appeal to one’s better self’. It has very little to do with genuine racial equality. Indeed, it is striking that in the Guardian, Tomasky put himself in the camp of ‘African-Americans and white liberals’ in contrast to the other camp: ‘young black men and old white men’. This is clearly not about race, per se, but about the aloof, elite sections of society who behave correctly (middle-class ‘African-Americans and white liberals’) looking down upon those who do not (inner-city ‘young black men’ or redneck ‘old white men’).

The racial divide today is less between white society and black people than between a new elite caste of sophisticated race-managers and ‘the rest’. And much of the loudest public support for Obama, that which emanates from the cultural elite, has been based on expressing this race etiquette rather than on trying to realise the goal of racial equality.

It is rich in the extreme for well-to-do liberals to pose as racially aware in contrast to working-class American voters. Throughout American history, there has been a great deal of racism and violence, yes, but there have also been instances of inspiring solidarity between blacks and whites at the bottom of the ladder against those at the top. In his 1994 book Towards the Abolition of Whiteness, David R Roediger told the story of a white union leader who in 1907 was accused of ‘conspiring with niggers’ to carry out an illegal strike. The union man said in his defence: ‘You made me work with niggers, eat with niggers, sleep with niggers, drink out of the same water bucket with niggers, and finally got me to the point where if one of them blubbers something about more pay, I say: “Come on nigger, let’s go after the white bastards”.’ (13) It’s not PC; there is no speech etiquette; it would certainly never be published in the Guardian, and would probably be labelled as hate speech today. But I far prefer that white union man’s solidarity with ‘niggers’ over today’s ostentatious backing of a black man as a way of demonstrating one’s moral superiority over the lower orders.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked. Visit his website here. His satire on the green movement – Can I Recycle My Granny and 39 Other Eco-Dilemmas – is published by Hodder & Stoughton. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Obama and the fall of ‘the silent majority’, by Frank Furedi

A victory for passion over cynicism, by Brendan O’Neill

Three cheers for the 140million voters, by Sean Collins

‘Hit the road, Jack’, by Guy Rundle

Paranoid British fantasists for Obama, by Mick Hume

McCain and Obama: products of therapy politics, by Sean Collins

Republican rallies: the myth of the crazed mob, by Sean Collins

Turning Sarah Palin into a 21st century witch, by Frank Furedi

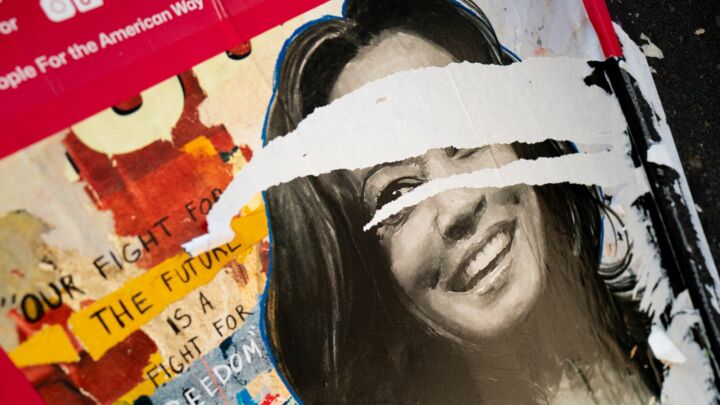

Please kill this Obama ‘assination porn’, by Brendan O’Neill

Obama’s Democrats: as conventional as ever, by Guy Rundle

The rise of Obama, the fall of Brown, by Mick Hume

Who is Barack Obama?, by Sean Collins

Why they’re scared of Obamamania, by Brendan O’Neill

Read more at spiked issue: America under Obama.

(1) It’s OK to vote for Obama because he’s black, Salon, 26 February 2008

(2) Colour blind, Guardian, 13 March 2008

(3) It’s OK to vote for Obama because he’s black, Salon, 26 February 2008

(4) Snowmail, Channel 4 News, 5 November 2008

(5) Colour blind, Guardian, 13 March 2008

(6) It’s OK to vote for Obama because he’s black, Salon, 26 February 2008

(7)

Obama the ‘Magic Negro’, Los Angeles Times, 19 March 2007

(8) The Silent War: Imperialism and the Changing Perception of Race, Frank Furedi, Pluto Press, 1998

(9) Black Anxiety, White Guilt and the Politics of Status Frustration, T Alexander Smith and Lenahan O’Connell, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997

(10) Black Anxiety, White Guilt and the Politics of Status Frustration, T Alexander Smith and Lenahan O’Connell, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997

(11) Race Experts: How Racial Etiquette, Sensitivity Training and New Age Therapy Hijacked the Civil Rights Revolution, Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn, WW Norton & Company, 2001

(12) Black Anxiety, White Guilt and the Politics of Status Frustration, T Alexander Smith and Lenahan O’Connell, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997

(13) Towards the Abolition of Whiteness, David R Roediger, Verso, 1994

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.