How Hillary became Empress of Ireland

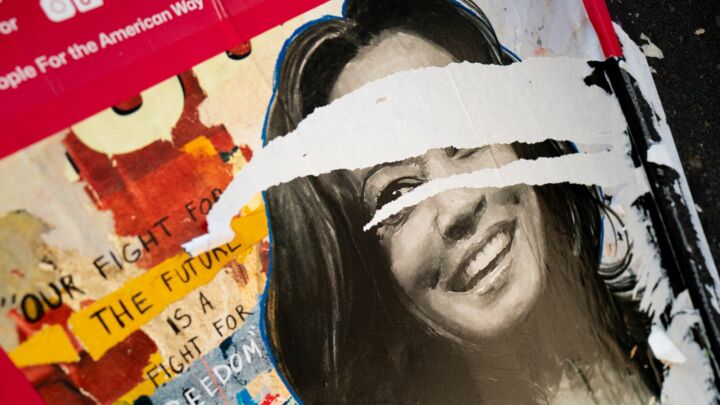

Hillary Clinton’s head-knocking visit to the Six Counties confirms that Washington has successfully conquered both Ireland and Britain.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Normally when an American secretary of state visits a foreign country to have stern words with its leaders or to knock some heads together, there is at least a flicker of controversy. Not so with Hillary Clinton’s visit to Northern Ireland. The British and international press are fawning over her apparent determination to deliver peace to that troubled island, hoping that she will complete her husband Bill’s ‘good works’ of the 1990s. ‘The Clinton approach to Ireland has been vindicated’, sang the UK Independent, claiming that Bill and then Hillary have shown that the Irish question is ‘not insoluble’ after all (1).

The gushing praise for Hillary Clinton’s visit shows how unquestioning commentators remain when it comes to America’s role in ‘delivering peace’ to Ireland. They continually overlook some basic facts about Washington’s Irish ventures of the past 15 years. They overlook the cynicism and opportunism that underpinned America’s interventions in Northern Ireland in the mid-1990s. They misunderstand the centrality of the Clintons’ Irish interventions to the rehabilitation of American foreign policy in the post-Cold War world, and to the reorganisation of Washington’s relationship with London and by extension with Europe. And they overlook how the transformation of Ireland into a political satellite for the Washington elite has further removed the democratic and political initiative from the Irish people themselves. Just like British imperialists before them, the new American rulers of Ireland are acting in their own interests rather than those of the Irish people.

Clinton has arrived in Ireland to give yet another injection into the arm of the ‘peace process’, the political initiative – if one can call it that – which has governed Northern Irish affairs since the early 1990s, through the IRA ceasefires of 1994 and 1997, and into the era of the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 and the forever-stalling Northern Ireland Assembly. Where the agreement was effectively strongarmed into existence by Bill’s interventions in Northern Ireland between 1993 and 1999, it is now being rescued by Hillary. She has held talks with Irish PM Brian Cowen and is today chairing talks between Sinn Fein and the Democratic Unionist Party on policing and justice. It is also no coincidence that the Irish National Liberation Army, a socialist republican armed group that was active between 1974 and 1998, announced 24 hours before Clinton’s arrival that it would follow in the footsteps of the larger Provisional Irish Republican Army and decommission its weapons: such a ‘breakthrough’ will have been carefully organised behind the scenes to bolster Hillary Clinton’s and Washington’s claims to be peacemakers in Ireland (2).

Hillary Clinton’s ability to dominate Ireland, to make grand public pronouncements on what Northern Ireland’s politicians ought to do next and why dissident republican groups should disarm, confirms Washington’s successful transformation of Ireland into an outpost for flexing its foreign-policy muscle. Where Washington has over the past 15 years run into big trouble in Somalia, Bosnia, Eastern Europe, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq, it has met with no resistance in its subordination of the Irish political agenda to Washington’s will. And its interest in Ireland has not been driven by a desire for peace, far less, as some republicans fantasise, by a secret American desire to bring about a united Ireland. Rather it has sprung from Washington’s determination to exploit the end of the Cold War in order to transform its relationship with its former imperial partner, Britain, and from the Bill Clinton administration’s desire to offset domestic and foreign failures by pursuing what it described as the ‘win-win scenario’ of ‘pushing for peace’ in Ireland, which posed few risks in terms of ‘US lives and financial expenditure’ (3).

President Bill Clinton first got involved in Northern Ireland in the mid-1990s because he considered it, in the words of Timothy J Lynch, author of Turf War: The Clinton Administration and Northern Ireland, a ‘suitable (if not ideal) test case of his international strategy’. American governments had previously colluded with London in accepting its domination of Ireland; ‘United States officials had an “empathetically interdependent” understanding of US-UK relations’, says Lynch: ‘Northern Ireland was London’s business’. But Clinton changed everything. He infuriated John Major’s Tory government, and ignored the advice of the FBI and the CIA, by granting an American visa to Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams in 1994, the ‘first and most visible manifestation of the new American attitude towards the Irish conflict’. Irish republicans were delighted with this move, not appreciating that Clinton was motivated, not by anything remotely resembling Irish republican sympathy, but by a cynical desire to ‘send a signal to London’ that, in the words of his national security staff director Nancy Soderberg, ‘President Clinton [intends to] irreversibly change the US role in Northern Ireland’ (4). The controversial Adams visa was followed by proposals from Washington to send a ‘peace envoy’ to Ireland, and Clinton’s appointment, in 1995, of former US senator George Mitchell as chairman of the All-Party Talks that generated the Good Friday Agreement. America, alongside Canada, also took responsibility for the decommissioning of paramilitary weapons in Northern Ireland (5).

That Washington was able to play such a key role in political and military matters in Northern Ireland – to the agitation of the Tory government and then to the relief of the New Labour government, which considered Bill Clinton a useful ‘partner in peace’ – reflected the changed realities of the post-Cold War era. It had nothing to do with ‘democratising’ Britain’s undemocratic arrangements in Northern Ireland; rather, through the issue of Ireland, Washington was effectively demoting Britain, with whom it had had a ‘special relationship’ during most of the Cold War era. If the ‘special relationship’ was somewhat torn and tattered towards the end of the Cold War in the late 1980s and early 1990s, then it was completely rewritten and redefined on the back of the Irish peace process from 1994 onwards. As Lynch argues, ‘The demise of the bipolar order [of the Cold War] meant the United States was less reliant on its relationship with Britain, inviting American intervention into a previously sacrosanct British sphere’ (6).

In The Making of US Foreign Policy, John Dumbrell and David Barrett argue that the Clinton administration viewed intervention in Northern Ireland as a way of signalling that there would be a ‘new, post-Cold War Europe’ in which American intervention would take different forms. ‘The ending of the Cold War made it easier for Washington to ignore London’s sensibilities’, they argue; or in the words of Irish-American writer Niall O’Dowd, ‘We were taking on 45 years of Anglo-American relations’ (7). Dumbrell and Barrett also point out that Mitchell – who is now the US peace envoy to the Middle East – told American business leaders in the mid-1990s that ‘investment in a peaceful Northern Ireland can constitute a valuable bridgehead into the European Union market’ (8). If this is too conspiratorial an explanation for America’s interventions in Northern Ireland in the mid-1990s (a kind of mad Irish variant of the ‘it’s all about oil!’ argument), Mitchell’s promotion of Ireland to businessmen does still rather capture that his and Clinton’s interest in Ireland was far from selfless and peace-based.

The Tories’ anger at Washington was shortlived. From 1995 onwards, and in particular from the election of New Labour in 1997, officials in London began to accept that America was the organ-grinder in Ireland. This acquiescence itself reflected Britain’s increasingly second-rate position in the post-Cold War world, to such an extent that it no longer held complete authority over what it defined as a part of its own state. As Dumbrell and Barrett argue, ‘London’s post-1994 adoption of a slightly more positive attitude towards American involvement seemed to embody an acceptance of the new, post-Cold War power relations’ (9). Yet if the Clinton administration’s intervention in Ireland was a way of redefining American power in relation to Britain and Europe after the end of the Cold War, it was also a desperate attempt by Clinton officials to offset their own crisis of legitimacy by adopting a ‘low-risk international initiative’.

As Lynch complains, ‘Clinton’s initial shift in US Northern Ireland policy – the Adams visa of January 1994 – is rarely put into the context of failing foreign policy’. And yet that visa was granted, against the wishes of both the CIA and the British government, just as there was a ‘general collapse in Clinton’s international strategy’. The early months of the Clinton administration were defined by failures and bloody interventions in Bosnia, Somalia and Haiti, and by a collapse of faith amongst the American public in Clinton’s promise of ‘domestic renewal’ (10). The search was on, says Lynch, for a ‘painless, no-lose foreign policy’ that might reinvigorate the Clinton administration’s sense of domestic prestige and international purpose. For this reason, the Clintonites latched on to ‘low-risk Northern Ireland’ as a way of both demonstrating their international power and restating their commitment to core American values.

As President Clinton himself said: ‘Why did the people of Northern Ireland, after the English and the Irish and the Protestants and the Catholics had been fighting for 800 years, want the United States to help bring peace to Northern Ireland? Why? Because they know we stand for freedom and democracy and fairness and opportunity, and we know this is the greatest country on Earth.’ (11) For Washington, this was not about delivering peace to Ireland, far less democracy and justice (things that cannot, by their very definition, be delivered to a country from without). Rather it was an attempt to project a new vision of the American mission at a time of a profound crisis of legitimacy and authority in Washington, at a time when Washington officials were still reeling from the demise of Cold War institutions and the emergence of a new, ill-defined, still-fluid world order. Northern Ireland was ‘an issue chosen by the Clinton administration (rather than forced on it by strategic necessity) in order to promote its reputation and secure its historical [standing]’, says Lynch (12).

The Clintonites also used the Irish issue to redefine Washington’s foreign policy, to shift it away from the calculated, strategy-based, realpolitik agenda of the clearer Cold War period towards something supposedly more ‘humanitarian’, emotion-based and instinctive. It is really through the Irish interventions that Washington first started talking openly about the role of emotion and feeling, as well as pity and sympathy, in driving its foreign-policy interests. Nancy Soderberg said Ireland confirmed what the Clintonites were starting to believe: that ‘emotion had a proper role in the formulation of foreign policy’. The Irish ambassador to the US in the 1990s explained Clinton’s interest in Ireland as springing from his ‘instinctual urge to side with the underdog’; where previous American leaders tended to ‘gravitate to power and dominance’, he said, Clinton’s Irish venture showed that he was ‘very sensitive to the concerns of those on the wrong side of the tracks’ (13). Here, Washington’s Irish venture played a key role in the development of new forms of American foreign policy, based more on ‘instinctual urges’ and a desire to rescue and protect the ‘underdogs’ rather than anything so old-fashioned as the pursuit of ‘power and dominance’. After the Irish venture, Clintonites began to argue more explicitly that, in both state-building and military missions, ‘values [must come] before interests’ (14). And as we have seen everywhere from Kosovo to Afghanistan to Iraq, a foreign policy built on the unrooted, unwieldy emotions of pity, and on a desire to advertise the selfless Washingtonian values of ‘fairness and opportunity’, can prove as disastrous as the old power-driven wars of old.

Some will say, ‘So what if London was elbowed aside by Washington?’ After all, London’s division of Ireland and governance of Northern Ireland was hardly democratic to begin with. Certainly this is why many Irish republicans have welcomed the Clinton family’s adoption of Ireland as a pet issue: because they know that it sidelines the British government whom they have traditionally opposed. But there is nothing to celebrate in the usurpation of British power in Ireland by American power. So long as the agenda in Ireland is driven, not by what the people of Ireland want, but rather by what Washington needs – whether it is to restate its ‘values’ or to reprimand its former partners in London or to give birth to new forms of underdog-siding foreign policy – then Ireland will remain beholden to external power interests rather than being shaped by internal democratic will. Hillary has arrived in Ireland to ‘breathe life’ back into the stalling, directionless institutions of the peace process – not realising that those institutions are stalling and directionless precisely because they were carved according to the needs of her husband and his elite rather than emerging from the democratic wishes of the Irish people.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked. His satire on the green movement – Can I Recycle My Granny and 39 Other Eco-Dilemmas – is published by Hodder & Stoughton. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Previously on spiked

Brendan O’Neill saw Hillary Clinton as a man in a woman’s world. Helen Searls explained how the tone of the presidential race turned from ‘Hillary hate’ to ‘Hillary hurrahism’. Sean Collins examined the identity wars between Clinton and Obama. Guy Rundle predicted that Hillary might split the Democrats in two. Or read more at spiked issue USA.

(1) The Clinton approach to Ireland has been vindicated, Independent, 12 October 2009

(2) Reaction to INLA renouncing violence, BBC News, 11 October 2009

(3) Turf War: The Clinton Administration and Northern Ireland,Timothy J Lynch, Ashgate, 2004

(4) Turf War: The Clinton Administration and Northern Ireland,Timothy J Lynch, Ashgate, 2004

(5) Northern Ireland: Key Issues: Decommissioning, Northern Ireland Office, 2009

(6) Turf War: The Clinton Administration and Northern Ireland, Timothy J Lynch, Ashgate, 2004

(7) The Making of US Foreign Policy, John Dumbrell and David Barrett, Manchester University Press, 1997

(8) The Making of US Foreign Policy, John Dumbrell and David Barrett, Manchester University Press, 1997

(9) The Making of US Foreign Policy, John Dumbrell and David Barrett, Manchester University Press, 1997

(10) Turf War: The Clinton Administration and Northern Ireland, Timothy J Lynch, Ashgate, 2004

(11) Turf War: The Clinton Administration and Northern Ireland, Timothy J Lynch, Ashgate, 2004

(12) Turf War: The Clinton Administration and Northern Ireland, Timothy J Lynch, Ashgate, 2004

(13) Turf War: The Clinton Administration and Northern Ireland, Timothy J Lynch, Ashgate, 2004

(14) Turf War: The Clinton Administration and Northern Ireland, Timothy J Lynch, Ashgate, 2004

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.