The assault on Assange is an assault on liberty

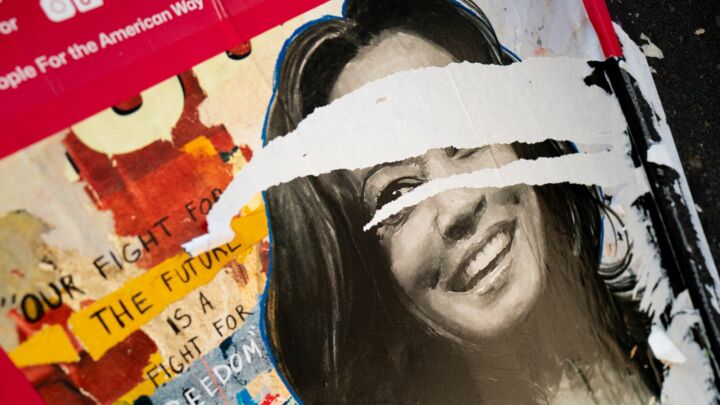

A desire to prosecute Assange has become a rare point of consensus in America’s hyperpartisan political scene.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Julian Assange is not Wikileaks; in other words, whether you regard him as a hero, villain, victim or egotistical malcontent, Wikileaks itself remains difficult to characterise. If it can be blamed for deterring diplomacy, derided for titillating us with diplomatic gossip, or dispensed with faint praise (by activist and writer Todd Gitlin) as the ‘Facebook of whistleblowing’, it can also be heralded for providing additional proof (if any were needed) of the gross hypocrisies and moral cowardice of the post-9/11 American security state.

Consider these side-by-side articles in the New York Times, describing just a few leaked cables: In 2006 and 2007, US diplomats successfully pressured German officials not to honour arrest warrants against CIA operatives who kidnapped and tortured an innocent German citizen, Khaled el-Masri. Two years later, the US was pressuring China to stop persecuting its dissidents.

This highly selective approach to human rights is as much a hallmark of the Obama administration as the Bush administration. Another leaked cable (described by Mother Jones) exposed the Obama administration’s efforts to stop the Spanish government from prosecuting high-ranking architects of torture under President Bush. No accountability for torture has been a guiding principle for each of our post-9/11 presidents. When El-Masri sued the US for his illegal detention and torture, the government invoked a state secrets doctrine and won dismissal of his claims. It also offered a state secrets defence in a lawsuit filed by Maher Arar, a Canadian/Syrian citizen who was kidnapped and tortured for 10 months before being released without charges. The Canadian government apologised to Arar and awarded him $10million in damages; the US government, under Bush and Obama, immunised itself behind a screen of state secrets. So which is more villainous: Wikileaks for releasing secret cables or the Bush and Obama administrations for pleading ‘state secrets’ to avoid accountability for summarily torturing innocent men? Or is that not a relevant question?

Has Wikileaks done more harm than the government it seeks to embarrass? It’s difficult to quantify the threat allegedly posed to American and international security by Wikileaks, but the threats to free speech and a free press posed by reactions to its recent data dump are quickly becoming clear. That Julian Assange is an enemy of the state and Wikileaks an exercise in anarchism (at best) or terrorism, not journalism, are rare points of bi-partisan agreement in the hyper-partisan American scene (and Assange is reportedly the subject of a federal grand jury investigation). Democrats and Republicans alike have urged indicting Assange under the 1917 Espionage Act, which includes provisions criminalising disclosures of classified information. Whether or not this law would or should allow for prosecution of media outlets (other than Wikileaks) that have received and published classified cables (but were not responsible for the original leak) is a subject of debate. But independent senator and former Democratic vice-presidential candidate Joe Lieberman, for one, is undeterred by concerns about a free press: he denounced the New York Times for publishing some of the leaked cables, accusing it of ‘at least an act of bad citizenship… whether they have committed a crime, I think that bears very intensive inquiry by the Justice Department’.

But the New York Times and other major publications are not alone in their potential vulnerability to Espionage Act prosecutions: an expansive interpretation of the Act could make it a crime for you to download the leaked cables or ‘post a link to Wikileaks on your Facebook page’, Louis Klarevas observed at theatlantic.com. Of course, this doesn’t mean that the Obama administration is about to indict anyone, much less everyone, who has downloaded and emailed copies of cables printed in the New York Times or elsewhere; but it does mean that federal prosecutors could conceivably claim the power to do so and use it to target people they’re anxious to prosecute for other reasons. As Harvey Silverglate warns in his latest book, Three Felonies a Day, one great danger of a vague, expansive criminal code is that it enables prosecutors to focus on people whom they want to prosecute rather than focusing on crimes that merit prosecution.

So it’s worth noting that the Obama administration insists that the leaked documents remain classified, even though they’re being published on the web. In a memo that managed to be both nonsensical and ominous, the administration warned unauthorised federal employees and contractors not to access any of the publicly available, yet classified documents. Officials at Boston University Law School and Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs passed on similar warnings to their respective students, out of concern that accessing leaked documents might harm their career prospects. (The dean at Columbia subsequently repudiated the suggestion that students should avoid exercising their rights to ‘discuss and debate’ public information.)

You can only hope they have the nerve to do so. The technology that enabled Wikileaks also enables the surveillance of people who follow it or download the documents it leaks. If diplomats can no longer rely on the privacy of their communications, neither can the rest of us.

I’m not suggesting that we should expect prosecutions of ordinary Wikileaks users, but I would not be at all surprised if young lawyers or international relations graduates seeking jobs in the government found themselves blacklisted for somehow ‘associating’ with Wikileaks. Historically, the treatment of alleged subversives or people found to have consorted with ‘subversives’, however fleetingly, is not reassuring, nor is the history of the 1917 Espionage Act.

A century ago, it was used to prosecute Emma Goldman and Eugene Debs for criticising the US government during wartime and opposing the draft. Goldman was deported and Debs subjected to a 10-year prison sentence, upheld by the Supreme Court. Goldman was arrested shortly after delivering a speech at an anti-draft demonstration in which she attacked the power of the president ‘to tell the people that they shall take their sons and husbands and brothers and lovers and shall conscript them in order to ship them across the seas for the conquest of militarism and the support of wealth and power in the United States’. Debs was convicted of obstructing the draft by announcing his opposition to the war and telling his audience, ‘you need to know that you are fit for something better than slavery and cannon fodder’.

These prosecutions and initial enactment of the Espionage Act, followed by the Sedition Act in 1991 (which included a ban on ‘disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language’ about the US government), occurred when the Supreme Court was just beginning to consider whether and when the First Amendment barred the government from criminalising speech. Gradually, the court acknowledged that the Bill of Rights imposed limits on state and federal power, but, thanks to early- and mid-twentieth-century red scares, people were successfully prosecuted under statutes prohibiting subversive advocacy through the 1950s. Not until 1969 did the court hold that mere advocacy was protected speech: in Brandenburg v Ohio, the court announced a relatively narrow definition of actionable incitement, as speech that’s intended to incite imminent acts of violence and is likely to succeed.

But this essential First Amendment freedom, slowly and painfully established in the twentieth century, did not long survive the twenty-first. This past year, in Holder v Humanitarian Law Project, the Supreme Court upheld a vague and arbitrary federal statute criminalising political advocacy when the executive branch declares, without evidence or due process, that it constitutes material support for terrorism. The prohibited speech at issue in Holder was advice about peaceful conflict resolution offered by a human rights group. If the Espionage Act is invoked against Wikileaks or if Congress amends the Act to ease and broaden its application in the digital age, today’s Supreme Court seems unlikely to protest anymore than the Court of 1919 protested the conviction of Eugene Debs for telling men they were not cannon fodder.

Civil liberties groups and some prominent bloggers have denounced the campaign to shut down information and debate by government officials and the private corporations that have stopped hosting Wikileaks. The private sector’s willingness to partner with the state has been a particularly bitter dose of reality testing for some. ‘Your free-speech rights are only as strong as the weakest intermediary’, a lawyer at the Electronic Frontier Foundation told the New York Times. That has long been true. Offline, authors and journalists without the support of publishers have had little if any chance of effectively disseminating their work. But the romance of the internet was an imagined promise of freedom from corporate as well as state control.

Hackers are rebelling, naturally; John Perry Barlow, co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, calls their guerrilla attacks in defence of Wikileaks ‘kind of the shot heard round the world’. Perhaps; but this revolution seems less likely to end in a resounding defeat of the state. Right and left, America is giving up on liberty. That is one lesson, or reminder, offered by the Wikileaks debacle (a lesson that seems to have resonated more in the European than the mainstream American press). I have heard only one prominent elected official – quirky, libertarian congressman Ron Paul – question the rush to censor Wikileaks and indict Julian Assange.

The silence of conservative politicians – putative advocates of small government – is not surprising. Right-wing protests of big government are essentially tax protests (unaccompanied by willingness to accept a reduction of benefits or services the protesters enjoy). The silence of liberal politicians is a bit more telling; it confirms that they’ve been effectively co-opted by Obama’s continuation of the repressive Bush/Cheney war on terror, which liberals once assailed. Congressional liberals reared up in revolt this month against the president’s ineptly negotiated agreement with Republicans to extend tax cuts for the super rich, but they have generally ignored the administration’s reflexively repressive reaction to Wikileaks; so, it seems, have many of their constituents.

Liberal Democrats have dared to speak out against the tax deal partly because a majority of the public (and probably a bigger majority of their liberal constituents) has opposed extending upper income-tax cuts. (The success of Republicans in forging the tax deal they sought is just one more example of minority rule, facilitated partly by the incompetence or cowardice of the president and the Democratic Senate majority.) But a fearful public has strongly supported whatever measures the government asserts are necessary to prevent terrorism – from the summary detainment and torture of terror suspects to virtual strip searches and highly intrusive frisking of air travellers. This may or may not be the government people deserve, but it is one that many of them have demanded.

Wendy Kaminer is a lawyer, writer and free speech activist. Her latest book is Worst Instincts: Cowardice, Conformity, and the ACLU. (Buy this book from Amazon (UK).)

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.