Trayvon Martin and the myth of racist America

In the US, everyone with a cause to champion and an emotion to release is latching on to the teenager's murder.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The killing of black, 17-year-old Florida high-school student Trayvon Martin by self-appointed neighbourhood-watch captain George Zimmerman was a tragedy. The local police’s poor handling of the situation is a scandal. Throughout America, people have been in a state of shock over the murder and there has been a widespread outpouring of support for the Martin family, demands for justice and a vote of ‘no confidence’ against the police chief heading up the shambolic investigation. This reaction shows how much American society has moved on from previous eras of racial discrimination. Even so, some are arguing that Martin’s murder reveals American society to be as deeply racist as ever.

Addressing a congregation of hundreds at a Baptist church about 20 miles from the site of the shooting, civil-rights campaigner Reverend Jesse Jackson compared Martin’s killing to the murders of Emmett Till and Medgar Evers. Till, a 14-year-old black boy, was murdered in Mississippi in 1955 for allegedly whistling at a white woman. Evers, a 38-year-old civil-rights activist, was murdered by a white supremacist in 1963, also in Mississippi. In his speech, Jackson even evoked the murder of Martin Luther King, called Trayvon Martin a ‘martyr’ and expressed hopes that his death would motivate black Americans to organise against racism and inequality.

In other words, Jackson, and the many other activists and commentators who have compared Martin to Till in the weeks since his murder, are suggesting that racism is still a violent force in the States, that segregation-era attitudes live on. But is Florida in 2012 really comparable to Mississippi in the Fifties and Sixties? Is racial profiling – a term invoked repeatedly in the weeks since Martin’s death – today’s answer to the Jim Crow laws? Or is there something else behind the rush to frame this shameful event as a symptom of deep-seated bigotry? After all, the suggestion that the murder is an expression of endemic racism doesn’t ring true in light of the groundswell of support for the Martins and the near-universal condemnation of Zimmerman as a prejudiced vigilante.

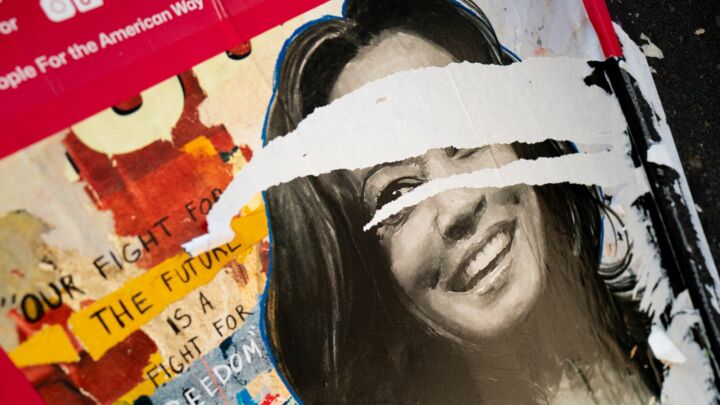

In fact, in the past few weeks, taking a stand against the killing has served as a kind of catharsis for many. From participants in solidarity demos to school pupils holding vigils and politicians addressing Congress, thousands have donned hooded sweatshirts – just like Martin did on the night he was killed – and waved placards saying ‘We Are All Trayvon Martin’. Others have latched on to the tragic murder to win approval for various causes. In such cases, although the concern for Martin and his family might be genuine, there is also a great deal of opportunism at play.

Jackson, for instance, expressed hopes that the killing will inspire ‘Trayvon Martin voter-registration rallies’. Gun-law reform proponents have said the case calls for a review of firearm legislation and, in particular, Florida’s ‘stand your ground’ provision. This rule allows a person to use deadly force in self-defence when there is reasonable belief of a threat, even if there is a chance to escape. Elsewhere, demonstrators participating in marches have waved placards that combine slogans demanding ‘Justice for Trayvon’ with slogans of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Others have drawn parallels between Martin’s killing in Florida and stop-and-frisk practices in New York, arguing that both are tied to racial profiling and so, they say, the New York Police Department now have an even greater responsibility to end the controversial practice. Also in New York, City Council speaker Christine C Quinn timed a protest against the handling of Martin’s killing to coincide with a vote on a new wage bill, which she sponsored. Before going in to vote Quinn, flanked by two dozen other council members, addressed a press scrum on the steps of City Hall. The council members wore hoodies and held bags of Skittles, just like Martin on the night of his death. Quinn is planning to run for mayor of New York City.

The clamour to identify with Martin, to state publicly that you are on his side and to demand an investigation into the killing, shows just how unacceptable racism is today in America. And so it is curious that so many are still drawing parallels between today and the era of state-sanctioned and socially accepted discrimination and violence against blacks.

No doubt, there are still racists around, as evidenced by offensive posts about Martin online, including on the white supremacist website Stormfront. There is also a great deal of prejudice out there, as shown by attempts by right-wing bloggers to present Martin as a menace. But there is, thankfully, far less state-sanctioned discrimination against black people. Racism is not endemic. To claim, as several anti-racists have, that Zimmerman’s killing of Martin was a modern-day lynching is pure hyperbole. Beyond a few hate-spewing cranks, you’d be hard pressed to find anyone who openly defends attacking black people because they are black. Today, the US has a president who can say of a boy like Trayvon Martin that, if he had a son, he would look like him.

The case far from fits a simple narrative of white racism. Zimmerman is a dark-haired, dark-skinned, half-Latino man who reportedly has mentored black children. He has, however, been repeatedly described in the media as ‘white-Hispanic’, prompting conservative pundits to accuse the mainstream press of shoehorning the story into a narrative of white-on-black violence.

Neither does the case fit easily into familiar claims of institutional racism. Zimmerman was not part of the police force. He was more, it seems, akin to a vigilante, acting alone and out of as-yet unknown motives, though he has claimed that Martin attacked him and that he was acting in self-defence. The police, however, should be held to account for failing to launch an immediate investigation and for not following standard procedure; for instance, Zimmerman did not take an alcohol or drug test on the night of the shooting.

No doubt, the politicians, activists and participants in the marches mean it when they say they are horrified by the killing and want to see justice done for Martin. But it also seems that there is a desire to phrase this unfortunate incident in the familiar terms of black victimisation. This urge to compare it to a period which is universally recognised as a dark blotch on the history of the United States oddly gives people a sense of comfort and righteousness. Here is something we can all agree is wrong, something we can all stand up against, something we can rally around and condemn collectively. And so Martin is being turned into a martyr for disparate causes – from voter registration drives to election campaigns, from anti-capitalist protests to anti-gun activism – in order to lend them moral credence.

Martin was unlucky to cross paths with a seemingly paranoid neighbourhood-watch captain, but at least it is comforting that his murder has shocked the nation. It shows that the killing of black people is anathema to, and not typical of, contemporary American society.

Nathalie Rothschild is an international correspondent for spiked. Visit her personal website here. Follow her on Twitter @n_rothschild.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.