The culture war over ‘Foxy Knoxy’ continues

The trials of Amanda Knox have become an excuse to attack the Italian national character.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

For the family of Meredith Kercher, the 21-year-old British student murdered in Perugia in November 2007, a final, truthful explanation for what happened, and who was responsible, seems as distant as ever.

Yes, Raffaele Sollecito and, most prominent of all, Amanda Knox, were last week found guilty once again of Kercher’s murder (alongside Rudy Guede, the one defendant against whom there is compelling evidence, who was convicted in 2008). But this is far from conclusive. After all, Knox and Sollecito were first found guilty in 2009, before their convictions were overturned on appeal in 2011. These acquittals were themselves overturned by the Supreme Court of Italy in Rome last year, and Knox and Sollecito’s case was sent back to appellate level to be tried again. So while this latest court review of the case has reinstated the original verdicts, it does not mean it’s over. Knox and Sollecito will appeal, and it looks as if the case will eventually end up being retried in Italy’s Supreme Court at some point in the next two years.

But the profoundly inconclusive, clarity-resistant nature of this case isn’t just due to the slow, inquisitorial nature of Italy’s justice system, where the process of judgement can pass through multiple layers of judicial seniority before something resembling finality is achieved. It also lies in the very causes of the case’s spectacularly high profile. In other words, finality, clarity, justice even, seem so elusive because the case has long since ceased to about what happened in that Perugian cottage over six years ago. It is now almost entirely about one person: Amanda Knox.

Or more accurately, it is almost entirely about what the warring international factions think of Knox. Guilt or innocence is no longer a question of due process, of evidence gathered and presented; rather, it now seems to be attributed according to which journalist’s vision, which biographer’s character portrait, people find most convincing. The bias is bewildering. You can read one report of the case in one newspaper and are left convinced that Knox is a wrong ’un; read another and you find yourself convinced that Knox has been wronged. And that is why the whole thing lacks any sense of potential closure. Because whatever the eventual decision of Italy’s Supreme Court, this battle between those who think Knox is innocent and those who think she’s guilty will never really end. They have too much invested in the case, and much of it unrelated to the actual murder.

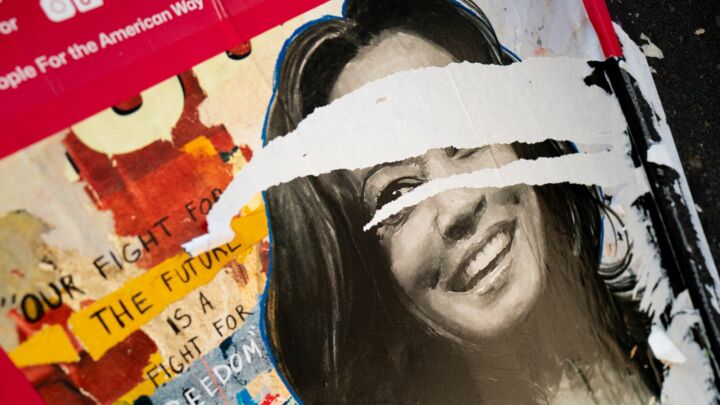

Almost from the moment Knox, alongside her then boyfriend Sollecito, was implicated back in November 2007, this battle to portray a particular image of Knox had begun. Initially, it was Knox’s sex and sexuality that was under the media microscope. She was presented as the epitome of hedonistic, morally lax, liberal America, condemned, it seemed, for having had the unfeminine temerity to have had sex with more than one man. Indeed, it has since emerged that the Italian police tricked Knox into talking about her sexual past, before turning the admission into something approximating evidence for the prosecution. More infamously, this was also the moment the soubriquet ‘Foxy Knoxy’, used first by the British journalist Nick Pisa, entered the popular imagination, and cemented her reputation as some sort of sinister temptress. That this nickname referred to Knox’s footballing skills rather than her seduction technique hardly mattered. It was enough that it seemed true.

From November 2007 onwards, Knox’s behaviour, rather than actual evidence, was relentlessly publicised and scrutinised. Her failure to show what was deemed the correct emotional response to Kercher’s murder, first in those now-infamous pictures of her hugging and kissing Sollecito outside the house where her friend had been butchered, and then in her much-reported cartwheeling insouciance at the police station, was transformed into an indication of both her guilt, and her sociopathic character. Prosecutor Giuliano Mignini’s assertion that Knox and Sollecito had killed Kercher as part of some Satanic sex ritual merely iced the cake of Knox’s demonisation. Just to reinforce this impression of Knox, lawyer Carlo Pacelli declared during her appeal that ‘She was a diabolical, Satanic, demonic she-devil. She was muddy on the outside and dirty on the inside. She has two souls, the clean one you see before you and the other.’

The prosecutors never really seemed to be trying Knox herself exactly. Their conviction in her guilt continues to seem overdetermined, as if there’s something else at work. Indeed, at some semi-conscious level, the prosecutors’ target seems to be as much a particular set of values, a national character even, as it is Knox the individual. She has been made to represent the liberal American dream turned seedy; her partying and her perceived promiscuity are deemed to illustrate America’s lack of a moral compass, its decadence. And the fact that in the course of police cross-examination, Knox fingered Congolese pub owner Diya ‘Patrick’ Lumumba as the culprit even bought white America’s perceived racism into play – it was the idea of America’s racism, remember, that fuelled the student-ish demonstrations against Knox’s acquittal in 2011. There was a lot on trial, and much of it unrelated to the rather mundane figure of Knox herself.

Yet, if the initial prosecuting focus on Knox was flecked with misogyny and anti-Americanism, the largely US-based defence of Knox has been no less brimming with prejudice and national caricature. The ostensible target has been Italy’s entire justice system. One account in Rolling Stone’s defence of Knox described it as ‘carnivalesque’ with ‘the lawyers and defendants constantly interrupting the proceedings with groans and catcalls and wild gesticulations, while the press in the gallery yammers away like the kids in the back of the classroom’. In New York magazine, a columnist responded to the reinstatement of guilty verdicts by calling Italian law ‘totally insane’, while another writing in the Atlantic said that Knox’s conviction was an ‘illogical clumsy disaster’ from the outset. As Andrea Vogt, a journalist long convinced of Knox’s guilt, felt the need to point out, the American dismissal of the most recent verdict ‘makes a mockery of the Italian magistrates who professionally managed this appeal, and who regularly risk their lives prosecuting the mafia in that very same courtroom’.

But beneath the sudden critical interest in Italy’s justice system – something that was notably absent during the trial of Italy’s former president Silvio Berlusconi – there lurks an attack on Italy just as nationally stereotyped as that of those oddly convinced of Knox’s guilt. For this coterie of opinion, Knox was not the devilish protagonist; she was the angel-eyed victim. The victim, that is, of Italy’s recidivism, its Catholic backwardness, its retreat into pre-rational mysticism and misogyny – all manifest in the seemingly impenetrable proceedings of Italy’s justice system.

So while one US commentator slammed the ‘non-existent motive’ of a Satanic sex game attributed to Knox, he also felt the need to point out why Italian prosecutors and jurors still bought it: because it ‘played to medieval superstitions’. In the Guardian, another pundit noted the persistence of the ancient in the Italian present, likening the trial of Knox to a fifteenth-century witch-hunt. In this view, Mignini and his fellow prosecutors were simply drawing on ‘the open strain of irrationality and misogyny that exists as an undercurrent in many headline-grabbing criminal cases [in Italy]’. In a piece written this weekend, the same pundit slammed what she saw as the ‘rank species of misogyny’ at work in the conviction of Knox. And in the Los Angeles Times, leading pro-Knox journalist Nina Burleigh was unequivocal: ‘In person, in prison and in the media, Knox was subjected to all manner of outlandish, misogynistic behaviour.’ Given Knox supporters’ disdain for Italy, its justice system, and what seems to have been conjured up as its nasty, woman-hating culture, it really doesn’t matter what the court eventually decides: the verdict will be corrupt.

Knox is now more than simply the main attraction in an increasingly turbid murder trial. She is now a vehicle for opposing prejudices and national caricatures. This has long since ceased to be a criminal trial; it has become an intractable culture war in which the prospect of justice seems further away now than ever.

Tim Black is deputy editor of spiked.

Picture: Mark Lennihan/AP/Press Association Images

Correction: the original article stated that it was prosecutor Mignini who described Knox as ‘a diabolical, Satanic, demonic she-devil’. It was actually Patrick Lumumba’s defence lawyer.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.