Regulating sex: the fear of intimacy

Students’ feelings of vulnerability are driving the regulation of sex on campus.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

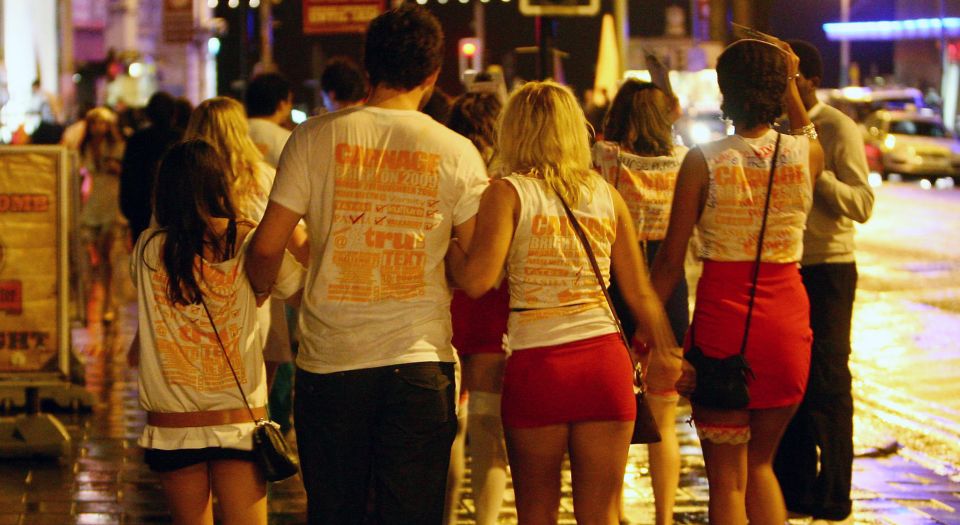

The long summer vacation used to be a time for university students to go inter-railing through European cities and discover the meaning of life, and each other, through sharing bottles of cheap wine. This year, the UK’s National Union of Students (NUS) is spending August promoting its recently published Lad Culture Audit Report. This is the latest in a series of reports designed to lend credibility to the NUS’s ongoing crusade against all things laddish. Despite the use of ‘audit’ and ‘research’, there is little objectivity in the report’s assumption that higher education fosters ‘rape-supportive attitudes, sexual harassment and violence’.

The report calls for ‘a new national framework to aid those affected by sexual violence and harassment’. This is a demand for a UK version of the US’s ‘Title IX’ regulation, a prohibition against sex-based discrimination in education which also rules on how colleges deal with allegations of sexual harassment and sexual assault. Currently, about half of UK universities have specific policies relating to sexual harassment – the authors of the Lad Culture Audit consider this to be symptomatic of ‘the problem’. They are further outraged by the fact that just 32 per cent of universities run official NUS-led sexual-consent workshops, and that only six per cent of institutions cover consent as part of the curriculum.

Throughout the report there is a sense of exasperation at this lack of consistency. That some institutions may not consider lad culture to be a huge problem, or may not have formal classes or policies in place to dictate to students how they should conduct their sex lives, clearly baffles and infuriates the authors. Special outrage is reserved for those universities that have ‘advised victims to try to resolve matters “informally” first, forcing them to take responsibility for difficult situations instead of seeking help from the institution’. The report’s unquestioning use of the victim label tells us why the authors find the idea of students, as adults, talking issues through with one another so baffling. The call throughout the report is for more explicit and formal regulation of how students behave towards each other.

Perhaps the NUS would like UK universities to emulate Goucher College in the US. This tiny liberal-arts college has a 33-page-long policy document called ‘Policy on Sexual Misconduct, Relationship Violence and Stalking’. Composed as a requirement of Title IX, it details the provision of educational programmes on sexual misconduct, relationship violence and stalking for all students, with the aim of preventing dating violence, domestic violence, sexual assault and stalking. The policy emphasises the importance of consent and offers the following definition: ‘Each participant is expected to obtain or give verbal consent to each act of sexual activity. In order for consent to be valid, all parties must be capable of making a rational, reasonable decision about the sexual act, and must have a shared understanding of the nature of the act to which they are consenting.’

This 33-page policy, which spells out in minute detail what the college’s 2,173 students can and cannot get up to in their bedrooms, makes for strange reading. Its declaration that consent cannot be given by people who have consumed alcohol or drugs, and they must therefore abstain until sober, suggests college administrators have lost all touch with reality. The problem the policy amply demonstrates is that when you start regulating the sex lives of students, there is no obvious place to stop. The Goucher policy goes on to prohibit ‘unwelcome flirtation, advances, inappropriate social invitations, or unwanted requests for sexual favours’.

What underpins both the NUS report and US Title IX policies is an assumption that students cannot be trusted to negotiate sexual relationships themselves. They are driven by a tangible sense of fear that allowing relationships to be unregulated by policy documents and consent classes will unleash violence and harassment. Uncontrolled sex and relationships are portrayed as dangerous and abusive. Passion, emotion, desire, instinct, abandon, especially when fuelled by alcohol, are to be reined in at all times. It is this fear of unregulated behaviour that lies behind demands for sexual-consent classes and policies.

If we go back a couple of generations, student sex was far more tightly regulated than it is today. Social, religious and cultural norms, driven in part by a very real fear of unwanted pregnancy and the stigma surrounding it, were enforced by authoritative adults in the guise of net-curtain-twitching neighbours at home and tutors acting in loco parentis on campus. Universities had single-sex accommodation and enforced curfews. Later on, the increased availability of contraception and the relaxing of such stifling social conventions were experienced as progressive and liberating. In 1970, the legal lowering of the age of majority in the UK from 21 to 18 reflected a recognition that students, as adults, were free to make their own mistakes in sex and relationships, as in every other part of their lives.

Of course, legal changes did not immediately alter social attitudes, and some regulation of young people by the enforcement of cultural expectations has continued. In particular, there was a general assumption of sex being linked to intimacy and emotion, even if not always conducted in the context of a relationship. But for many of today’s students, sex has been separated from emotional intimacy. School children are taught to be suspicious of strangers, that other children may be bullies, that it is best to avoid ‘exclusive’ friendships, and that sexual relationships can be violent and abusive. All too often, children learn to avoid making themselves vulnerable by emotionally investing in other people.

This fear of intimacy comes at a time when there are few social or cultural stigmas surrounding sex. Far from the moral disapproval of yesteryear, parents of today’s teens are advised in newspaper columns and on internet-discussion boards to allow boyfriend/girlfriend sleepovers in order to ensure openness and safety. Modern parents are supposed to leave a jar of condoms in the bathroom, turn the music up and chill out.

But this seemingly more liberal attitude keeps sex at the emotional level of the sleepover party. Today, the ‘safety’ sought by protective parents is only in part to do with avoiding becoming a premature grandparent. Instead, it is driven by a fear that their child might be pressurised into doing something he or she feels uncomfortable with – that he or she may be abused or emotionally harmed. Our conception of sex has been divested of intimacy and separated from feelings stronger than friendship. As a result, it breeds permanent suspicion. Young people are told not to trust each other, and not to trust their own ability to cope if things go wrong.

The students now calling for new regulations, classes and policies to regulate their sex lives are reacting to the moral relativism of the adult world. Rather than celebrating sexual liberation, they experience a fear of uncontrolled behaviour, particularly behaviour that takes place in private and may lead, in moments of intimacy, to emotional vulnerability. New codes of conduct, rapidly being written at universities up and down the country, are, in reality, little to do with sex, and even less to do with rape. They are about regulating behaviour and setting formal restrictions on how people relate to each other. Students today, unable to trust themselves or each other, clamour for rules. Universities are rushing to play catch-up and, in the form of these insane regulations, are providing students with the safety they appear to crave.

Joanna Williams is education editor at spiked. She is also a lecturer in higher education at the University of Kent and the author of Consuming Higher Education: Why Learning Can’t Be Bought. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.