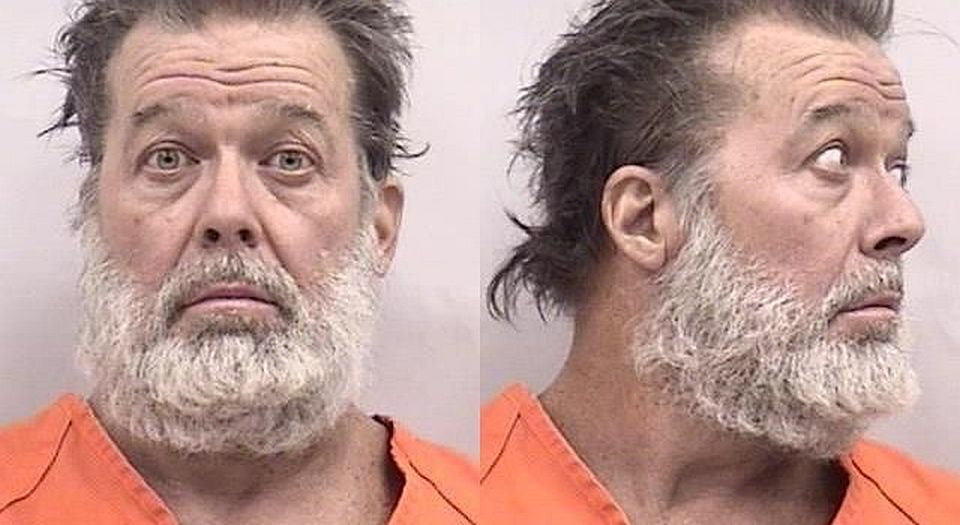

Planned Parenthood shooting: did words incite it?

No, words don't directly cause violence. But they do have great power.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Is the inflammatory rhetoric of some pro-life advocates responsible for murderous assaults on Planned Parenthood clinics? Are websites that promote jihad responsible for terrorism? Does pornography cause violence against women? ‘No’, is the free-speech advocate’s response to these and similar questions about presumptively harmful speech, and I agree that violence can’t simply be blamed on language that allegedly encourages or excuses it.

Legal questions about the limits of free speech linked to violence are relatively easy to answer. In 1969, the US Supreme Court enunciated a narrow, workable standard protecting distasteful political advocacy up to the point when it directly and intentionally incites ‘imminent lawless action’, in a context in which such action is ‘likely to occur’.

Epistemological questions about the relationship between speech and action, however, are not resolved by standards like this, much less by yes or no answers to questions about causation. Words are not incantations. They don’t cast spells. But they do have power. If I didn’t believe in the capacity of language to provoke, persuade and otherwise influence people, I wouldn’t be a writer, or, at least, I wouldn’t bother publishing my writing.

Yes, primary responsibility for murder rests with the murderer, whether he kills people out of anger, ideology, vengeance, sociopathic tendencies, or all of the above. But to deny that an armed assailant on a Planned Parenthood clinic may have been partly influenced by exhortations to stop the ‘holocaust’ of unborn babies, or that a shooter who randomly murders nine people at a black church may have been partly inspired by white-supremacist rhetoric, is to deny human nature, as well as the persuasive power of language, for better and worse.

After all, free-speech advocates oppose restricting allegedly hateful speech or generalised advocacy of violence partly because we believe that free speech has normative value, regardless of content (people have a right to harbour hatred and biases), but also because we know that what some consider bad speech can’t be regulated without also regulating what others consider good speech. One person’s hate speech is another person’s dissent. And virtually all of us, free-speech champions and censors alike, support the freedom of ‘good’ speech, partly because we agree that speech has the power to shape beliefs and actions, as well as the ability to reason.

So, without contradicting myself, I can oppose the regulation of speech that may arguably contribute to violence, or a culture amenable to violence, and still express a desire for advocates to ‘tone down’ inflammatory rhetoric. I can defend Donald Trump’s right to suggest that Muslim-Americans should be registered, and that protesters at his rallies deserve to be ‘roughed up’, and still assail the demagogic way in which he exercises his right.

The trouble is that criticising the content of speech invariably generates demands to restrict it. The distinction between opposing what someone says and opposing his right to say it is often lost in the political arena, especially, but not exclusively, during presidential campaign season. This is not a call to refrain from criticising the harsh, intemperate rhetoric of so much political discourse. But it is a reason for all of us to consider the possible effects of our criticisms, along with the possible effects of the rhetoric we criticise. All speech, stupid and smart, ‘good’ and ‘bad’, can have both intended and unintended consequences.

Wendy Kaminer is an author, lawyer, and civil libertarian.

Picture by: Handout/Getty

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.