A new Cold War?

Tensions may be rising, but Russia is not to blame.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Earlier this month, James Clapper, US national intelligence chief, announced that US intelligence agencies would be conducting a major review of alleged Russian funding of opposition parties in Europe. Russia, a senior unnamed British government official claims, is trying to destroy European unity on several political, social and military matters.

Now, it may well be the case that Russia has given money to Front National or Golden Dawn or UKIP or Jeremy Corbyn for all we know. After all, funding other nations’ opposition parties has always been bread-and-butter work for foreign powers, including the US secret service – it funnelled money into the so-called Colour Revolutions and armed groups in Ukraine and the Middle East. I’ve no doubt Russia does it, too.

However, the idea that Putin is behind the current refugee crisis and the longer-term political problems in the Eurozone is simply ludicrous. Not even the flimsiest understanding of the history of the past decade could support such a proposition. From the financial crisis to the crushing of the Greek economy to Angela Merkel’s unilateral decision to allow a million refugees into Germany, these developments can’t be put down to the actions of Russia.

Perhaps Russia is also behind the EU’s current headache, Poland’s governing Law and Justice Party, which is currently subject to an unprecedented inquiry into whether new Polish laws break EU law.

The only problem is the Law and Justice Party is one of the most rabidly anti-Moscow parties out there. Perhaps Cameron has also been receiving Moscow gold in exchange for pushing the UK towards a Brexit? I doubt it. It’s a fantasy that we are in some kind of Cold War situation, with Moscow funnelling gold into various groups with the aim of toppling the EU and creating discord. If only it were that simple. Thanks, Putin, but save your money for the crashing Russian economy. The EU is managing to disintegrate entirely on its own.

These overblown claims are part of a trend. It has become common for politicians and the media to discredit Putin with tales of corruption and murder. The Litvinenko farce and Clapper’s comments show that the Western propaganda mill is once again cranking into action. Why is this happening?

For several years now, military and political tensions between Russia and the West have been growing. The Ukraine crisis, rather than being the cause of worsening tensions, actually represents the emergence of these tensions. But these tensions are not the result of Russian revanchism or aggression. Much of the blame lies with Western foreign policy.

Over the past 20 years, several developments have worried Moscow – particularly the rise of Western military intervention. The intervention in Kosovo in 1999 was a decisive moment: NATO acted outside of its mandate, becoming a kind of free-floating Western military force. The invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan were also catastrophic: the US, UK and other allies destroyed two countries without fully understanding what they were doing. The intervention in Libya, although originally supported by Russia, soon tipped over into incoherent regime change, the consequences of which are still unfolding. If anyone is to blame for overturning the postwar international order, it is the West.

NATO has expanded relentlessly, first taking in the Baltic republics, then Albania and Croatia in 2009. Bosnia, Macedonia, Montenegro and Georgia are now in the waiting room. A strategic alliance should be just that: strategic. Would the West seriously want to go to war over any of these states? Within Montenegro itself there have been serious protests against joining NATO. Of course, for the likes of the BBC, this fact is presented as yet more evidence of Russian subversion. The fact that, in 1999, Montenegro, then part of former Yugoslavia, was bombed by NATO can’t possibly be of any relevance.

In Ukraine, the EU more or less staged a coup by going to Kiev and ordering the elected Ukrainian government to go. This precipitated the most dangerous crisis in Europe since the Cold War. This was not a deliberate attempt to stoke war, but a kind of accidental foreign policy in which the complex and genuine political and social disagreements within Ukraine itself were ignored (despite decades of excellent British and European scholarship on post-Communist Ukraine). The EU’s moral grandstanding over Ukraine was a catastrophic mistake.

There has been a relentless rise in NATO and Russian military exercises, and a frightening increase in the number of near-misses. The European security order (to the extent that it exists) is currently under threat from US plans to return troops to a number of former Warsaw Pact states. President Obama has just announced that his new budget will include a request to quadruple US military spending in Europe, with plans for heavy weapons and troops to be stationed along Russia’s borders. Turkey’s frankly deranged decision to shoot down a Russian jet in December, in the hope of sabotaging US and Russian talks over Syria, shows us just how unstable things are at the moment. Turkey is, of course, a member of NATO and therefore governed by Article 5, the principle of collective defence.

So is this a new Cold War? Not quite. While there are rising military tensions, there are many factors at play that were not present in the Cold War. For example, there is disagreement within the EU about Russian sanctions and the increase in the US military presence in Europe. This isn’t anything to do with Russian plotting – these are genuine political disagreements. Unless, of course, one happens to think that politicians such as Bavarian premier Horst Seehofer, long-term opponent of Russian sanctions, is in the Kremlin’s pay.

A very important difference today is the lack of public discussion about the rise in military tensions, and the potential for the crisis to escalate. Would anyone in the UK seriously want to go to war with Russia because Turkey chooses to take potshots at Russian planes? Would anyone in the UK want to go to war with Russia over Ukraine? It’s time for an open discussion about foreign policy. Do we want a new Cold War, with all the misery, expenditure and ever-present threat of a nuclear holocaust?

The idea that we have divergent interests from Russia simply cannot be sustained. At least in principle there were different ways of organising society at stake during the Cold War. This is not the case today. We have no divergence in interests with Russia; in fact, we have common interests – tackling ISIS, ensuring European security, maintaining oil prices, and so on. Russia doesn’t want to invade Lithuania or Poland or Latvia. Russia does not want to invade Ukraine. Russia does, however, have legitimate interests, and we need to take these seriously. We need to accept that Russia is a real country with real interests, just like our own, and not the pantomime villain the media are presenting it as at the moment.

Tara McCormack is a lecturer in international politics at the University of Leicester. She is author of Critique, Security and Power: The Political Limits to Critical and Emancipatory Approaches to Security, published by Routledge. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

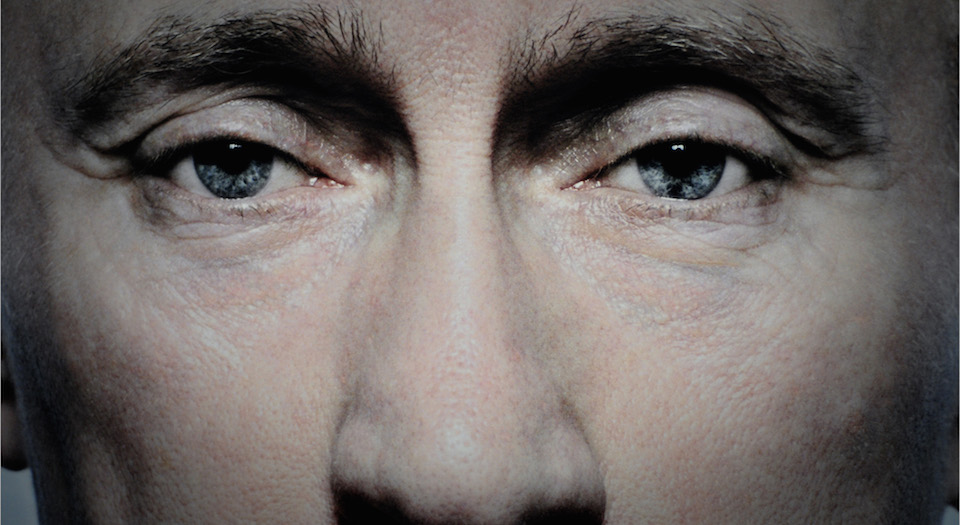

Picture by Firdaus Omar.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.