The (new) paranoid style in American politics

Claims that Trump is ‘Putin’s Puppet’ sound like left-wing McCarthyism.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

In 1961, the historian Richard Hofstadter wrote an essay for Harper’s Magazine called ‘The paranoid style in American politics’. Written in the wake of McCarthy – the demagogic Republican senator who saw Soviet shills everywhere – it’s a fascinating reflection on the conspiratorial strain in US politics, which, Hofstadter argued, was as old as the nation itself. He traced it through the anti-Masonic movement of the late 18th century, the anti-Catholic movement of the 1830s, and the populist agrarian-left of the late 19th century – all vocal fringes that were convinced America was beset by cliques of evil actors, plotting its downfall. This ‘sense of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy’, he wrote, set the stage for the McCarthyite era.

With the US election looming, Hofstadter’s essay is as pertinent today as it was then – but not in the way you might think. Yes, Donald Trump’s more vociferous online fanboys are wont to push heavily footnoted theories about Hillary Clinton being terminally ill and/or plotting a ‘socialist dictatorship’; but even respectable critics of Donald Trump are tapping into the paranoid style. And the parallels with the Fifties are striking. McCarthy acolyte Robert H Welch once accused President Eisenhower of being ‘a dedicated, conscious agent of the Communist conspiracy’. Today, the conspiracy theory du jour is that Trump is ‘Putin’s Puppet’, a useful idiot in hock to the Kremlin and being used as a weapon against Western civilisation.

Where once the right had sleepless nights over Communist (mostly Russian) agents, so today liberals think Vlad lurks behind Trump’s every move. And this comes straight from the top of the Democratic establishment. This week, in response to FBI director James Comey’s unprecedented decision to reopen the investigation into Clinton’s email server just 11 days before the election, Senate minority leader Harry Reid wrote to Comey to accuse him of a ‘disturbing double standard’. He alleged that the FBI is sitting on ‘explosive information about close ties and coordination between Donald Trump, his top advisers, and the Russian government’. This comes after a stream of news investigations claiming Trump has a private server connected with a shady Russian bank called Alfa.

The facts, of course, are a lot fuzzier. As the New York Times reports, the FBI investigated Trump’s links with Russia over the summer, as part of a broader investigation into Russia’s hacking of Democratic Party computer systems; it found ‘no conclusive or direct link between Trump and the Russian government’. The hacking into Democratic emails, the FBI concluded, ‘was aimed at disrupting the presidential election rather than electing Mr Trump’. Even lengthy investigative pieces in Slate and Mother Jones, based on interviews with hackers and anonymous intelligence officers, could offer nothing more than a ‘suggestive body of evidence’, and suggestive nudges and winks, as proof that Trump was in league with Alfa or the Kremlin.

These exhaustive articles hint to one of the central facets of the paranoid style: dot-connecting pedantry. As Hofstadter put it, paranoid literature has an ‘almost touching concern with factuality’. ‘McCarthy’s 96-page pamphlet, McCarthyism’, he noted, ‘contains no less than 313 footnote references, and [Robert H] Welch’s incredible assault on Eisenhower, The Politician, has 100 pages of bibliography and notes’. Even where clearcut proof evaded him, McCarthy would still hold up his constellation of factoids as too compelling to ignore. In his 1951 indictment of then secretary of state George C Marshall, McCarthy, Hofstadter wrote, insisted ‘there was a “baffling pattern” of Marshall’s interventions in the war, which always conduced to the wellbeing of the Kremlin’ (my italics).

Long before claims about Trump’s ‘hotline’ broke, liberal hacks were compiling evidence about his myriad links with Russia. In a piece for Slate titled ‘Putin’s Puppet’, Franklin Foer explored Trump’s ‘slavish devotion’ to Putin (who he has never met) and catalogued his advisers’ connections with Russian oligarchs. Paul Manafort, Trump’s former campaign chairman, worked with ‘clients close to the Kremlin’ and worked for Victor Yanukovich – the now ousted president of Ukraine. Michael Flynn, Trump’s defence adviser, was said to have ‘sat two chairs away from Putin at the 10th anniversary gala celebrating Russia Today’. ‘In the end, we only have circumstantial evidence about the Russian efforts to shape the election’, Foer concedes, ‘but the pattern is troubling’ (my italics).

As ever, the simplest explanation evades the paranoid mind. As Jacob Heilbrunn notes in the Spectator, ‘there is a long history of American capitalists… who enjoyed intimate relations with the Kremlin, never allowing moral scruples to get in the way of business’. Perhaps, he adds, the reason Trump is so given to ‘pro-Putin twaddle’ – ‘I think he’s done really a great job of outsmarting our country’, quoth The Donald – is that he actually believes it. But commonsense is cast out in favour of hysteria. ‘The paranoid spokesman’, as Hofstadter put it, ‘traffics in the birth and death of whole worlds, whole political orders’. ‘Vladimir Putin has a plan for destroying the West – and that plan looks a lot like Donald Trump’, concludes Foer.

We shouldn’t call this a new McCarthyism: five minutes on Infowars will show you that Team Trump are actually the real tin-foil-hat brigade. But the fact that prominent liberal sheets and serving Democratic politicians are promoting the idea that Trump is a witting – or witless – agent of the Kremlin shows that the paranoid style has gone mainstream. As Hofstadter noted, conspiratorial thinking has never been consigned to the right; in recent years, the dregs of the left have filled column inches with claims about cabals of bankers, press magnates and fossil-fuel corporations shaping society from the shadows. But in a time when even the centre-left longs for Cold War certainty, the echo of McCarthy still sounds.

Tom Slater is deputy editor at spiked. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

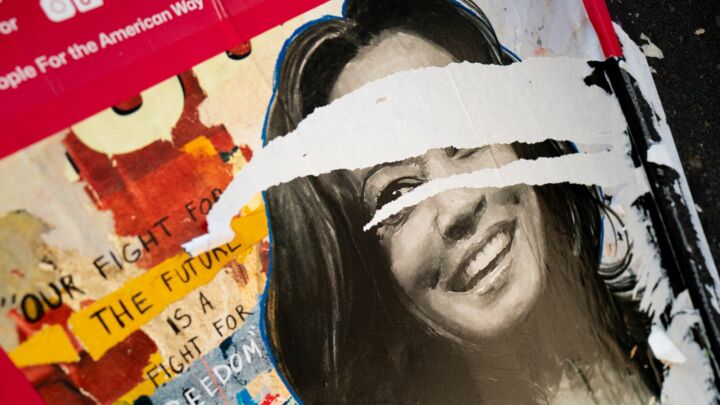

Picture by: Getty Images.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.