The paucity of economic thinking

None of the parties is offering the radical change we need.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Since the EU referendum last year, there has been much doom-mongering from many politicians about the potential impact of Brexit on the economy. So, you would think that a plan to turbocharge the economy, and snap it out of stagnation, would be front and centre of every manifesto for the upcoming General Election?

Think again. Of the main political parties, only Labour and the Tories lead with the economy. Both, however, kick off with taxes, rather than how to stimulate growth.

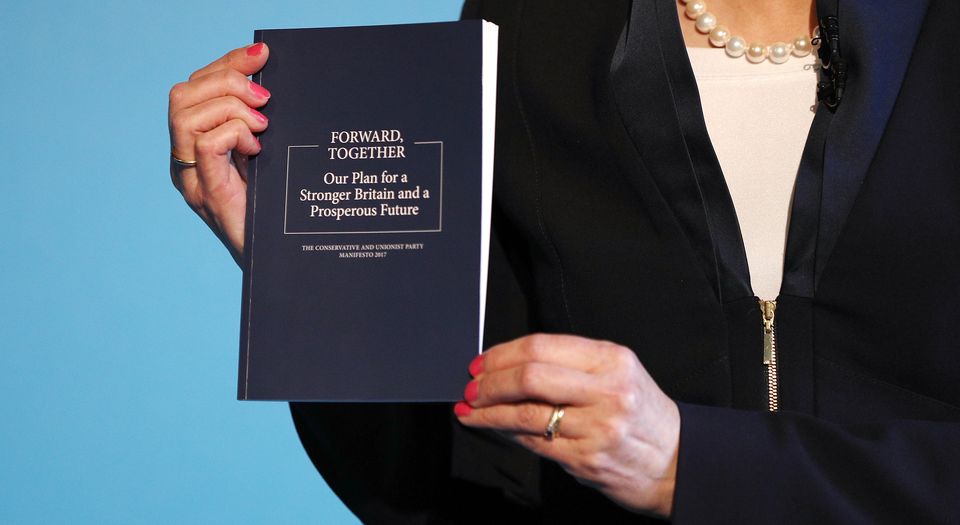

In fact, it’s only until about halfway through its section on the economy that the Tory manifesto even begins to talk about ‘a modern industrial strategy’. This comes after a chunky section on how businesses should be better regulated – from introducing new rules determining executive pay to better corporate governance.

Even then, the section on industry is hardly heady stuff. Indeed, it makes the government’s green paper, Building Our Industrial Strategy, which was published earlier in the year, seem teeming with ambition by comparison. While the Tory manifesto is the only one to mention the fundamental issue of the UK’s slow productivity growth, the proposed solution, which was announced in the Autumn Statement, remains woefully lacking: a £23 billion National Productivity Investment Fund to finance new industrial initiatives. This amounts to under five billion pounds a year, which, as economist Phil Mullan has previously pointed out on spiked, is less than half a per cent of annual output. Hardly enough to kickstart a fourth industrial revolution.

Likewise, when it comes to research and development (R&D), the Tories seem to think we should just play catch-up. They rightly identify that it is problematic that the UK lags behind the OECD average of 2.4 per cent of GDP expenditure on R&D. However, they give themselves a whole decade for the UK to overcome its below-average status – and a target of three per cent is cited in the ‘longer term’.

There is a commitment to the government’s strategic projects of HS2, Northern Powerhouse Rail and a third runway at Heathrow Airport, but very little is specified beyond that. It’s somewhat apt that the Tory Party manifesto ends its ‘industrial strategy’ section on a plan to expand infrastructure for cyclists. When it talks about the UK becoming a powerhouse, is it referring to pedal power?

The Tories do, at least, talk the talk about developing Britain’s shale industry. The manifesto rightly notes that the fracking ‘revolution’ in the US is ‘driving growth in the American economy and pushing down prices for consumers’. Not so for the Labour Party. Its manifesto states that the party would ban fracking, ‘because it would lock us into an energy infrastructure based on fossil fuels, long after the point in 2030 when the Committee on Climate Change says gas in the UK must sharply decline’.

This sets the tone for much of Labour’s manifesto. Rather than focusing on growth and innovation, it focuses on sustainability and regulation. ‘Our industrial strategy will be built on objective, measurable missions designed to address the great challenges of our times’, it states. First, it wants to ensure 60 per cent of the UK’s energy comes from zero-carbon or renewable sources by 2030. And second, it wants to hit the OECD’s target of three per cent expenditure on R&D by the same date.

Neither pledge is particularly positive, and both targets are well out of the range of the next term of parliament. The renewable-energy pledge would most likely harm growth, rather than stimulate it. For a manifesto that opens with Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn saying, ‘this election is about what sort of country we want to be after Brexit’, both of his suggestions are formulated to meet targets set by supranational bodies.

Meanwhile, Labour’s brief section on ‘upgrading our economy’ lasts a mere two-and-a-half pages – complete with large colour pictures. But acres of space is then dedicated to regulation of industry and corporate tax avoidance. ‘Our industrial strategy is one for growth across all sectors’, the manifesto declares at one point. If growth did manage to occur under a Corbyn government, it would probably be in spite of these policies.

The Liberal Democrats’ plan to ‘build an economy that works for you’ is buried in the middle of their manifesto. Wading through, there are a few nuggets that sound positive – building 300,000 new homes a year by 2022, for example. And they also promise ‘a programme of installing hyperfast, fibre-optic broadband across the UK’. But much of the focus is on how best to ‘spread opportunities’ and help everyone ‘share in prosperity’, rather than create more. Their primary concern is to better spread the wealth that currently exists, like a lump of butter on toast.

Things get even more downbeat when you move to the smaller parties’ pledges. Take this quote, for example: ‘Major infrastructure projects will be required to give much more respect to irreplaceable natural habitats. HS2 is a prime example of this: we will scrap HS2 and ensure no infrastructure project will ever again be allowed permission to wreak such catastrophic environmental damage.’ If you think this is a quote from the Greens, you’d be wrong. It belongs to UKIP.

UKIP’s manifesto begins by saying that the country needs ‘radical… economic change’, but focuses predominantly on the initiatives it plans to scrap, rather than what can be done to stimulate growth. Where there are plans, they hardly inspire. The best way to deal with the housing crisis? Cut immigration and then initiate a plan for a ‘modular-homes building scheme’. UKIP bends over backwards to stress that it isn’t proposing a return to postwar ‘prefabs’, describing affordable houses that sound just like, er, prefabs.

The Greens do dedicate a page to the economy in their manifesto, but it is a ‘green economy’ that is rather broadly defined: ‘The economy is all of us: our work, our creativity, what we buy, how we spend our time.’ Unsurprisingly, the party’s economic plans focus not on an industrial strategy, but on how to increase jobs through the expansion of the public sector, paid for by higher taxation on the wealth-creating areas of the economy. Exactly how many wealth-creating areas would be left, if the Greens somehow stormed to power next week, one can hardly bear to imagine.

In her introduction to the Tory Party manifesto, prime minister Theresa May says we should ‘make the most of the opportunities Brexit brings’. There is indeed a major opportunity for Britain to now forge strong trading links with the rest of the world, and take advantage of its departure from EU regulations to increase productivity and drive forward economic growth.

But what is most sorely needed now is some bold economic thinking and an ambitious industrial strategy, which would bring about the growth we need to become a world-leading economy following the Brexit vote. Despite this being the most important election in a generation, such bold economic thinking is noticeable only by its absence.

Patrick Hayes is a spiked columnist.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.