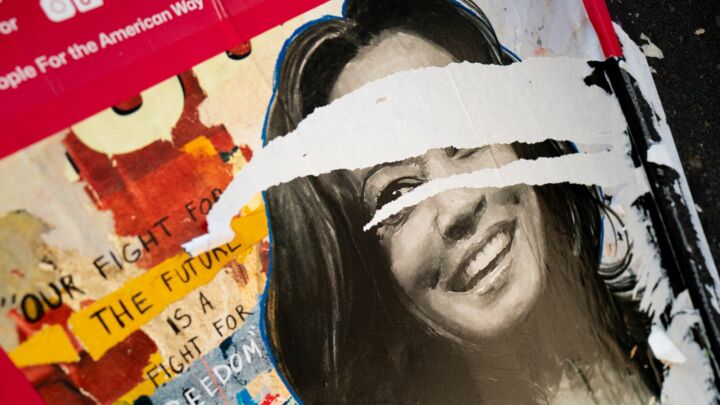

Judges shouldn’t Trump democracy

The travel-ban debacle reveals the dangers of judicial activism.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The US Supreme Court has partly lifted injunctions on President Trump’s travel ban against people from certain Muslim-majority countries. Trump signed the first travel-ban executive order in January, and a second, amended order in March. The aim was to suspend entry to foreign nationals from seven countries – Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen – deemed to present a heightened terror risk. (In the second order, Iraq was dropped from the list.)

The suspension was to last 90 days, while the government overhauled counterterrorism measures. This would have also suspended the US refugee resettlement programme for 120 days. But the orders were blocked by a series of rulings from federal judges, who deemed aspects of the ban unconstitutional. This forced the Trump administration to make some concessions.

The Supreme Court concluded that the scope of the injunctions granted by the lower courts were too wide. By barring enforcement of the ban against foreign nationals abroad who have ‘no connection to the United States at all’, the injunctions failed properly to balance the interests of national security with the burdens placed on individuals seeking entry to the US. The court indicated that it would hear substantive arguments on the legality of the policy later in the year. But these may be moot by then, as the travel ban is only scheduled to last 90 days.

Trump said the ruling was a ‘victory for our national security’. But, reading the judgement, it is far from a vindication of the substance of the policy. Indeed, the ruling is really a compromise – allowing those with a ‘bona fide relationship’ with a person or entity in the US to enter. The Trump administration has claimed that a ‘bona fide relationship’ would mean immediate family members only, and that even grandparents, grandchildren, aunts and uncles of US citizens would still be banned. This interpretation has been challenged by critics.

The travel ban has been much maligned as Islamophobic and racist, quickly becoming known as the ‘Muslim ban’. The lawsuits seeking to undermine it claimed that Trump’s remarks during the campaign about Islam demonstrated that the ban was motivated by an animosity towards Muslims, rather than concern about national security. Detractors have pointed out that the ban would not have prevented any of the recent terror attacks in the US, as none was carried out by a citizen of the banned countries.

Government lawyers and supporters of the ban have always claimed that it is a temporary and proportionate response to the need to reassess the quality of information coming from unstable foreign governments about prospective migrants to the US. Calling it a ‘Muslim ban’, they say, is absurd, given that the ban has no impact on countries with some of the highest Muslim populations in the world.

But whether the ban is driven by Islamophobia or not, it will continue to have huge consequences. The chaos at airports that followed the issuing of the order in January has, thankfully, not been repeated following the Supreme Court ruling last week. But US citizens have complained of the pointless bureaucracy that will now be necessary to bring family members into the country.

The Supreme Court decision also raises questions about American democracy. By introducing a new test into the ban, of establishing a ‘bona fide relationship’, the judges have, in effect, acted as legislators. Conservative commentator Laura Ingraham accused the justices of overreach, saying ‘they should resign their positions and they should go run for office’ if they wanted to make decisions of the kind they did last week.

Five judges of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals had already raised questions about judicial overreach before the case reached the Supreme Court. In a dissenting opinion, they said ‘whatever we, as individuals, may feel about the president or the executive order, the president’s decision was well within the powers of the presidency… the wisdom of the policy choices made by [the president] is not a matter for our consideration’. They warned of the danger of intervening in the power of the presidency, over which judges only have ‘narrow’ powers to review.

These are recurring questions in the American system. In reading the Supreme Court judgement, I wondered what the recently deceased Justice Antonin Scalia would have made of it all. Scalia, a notorious critic of judicial activism, died in February 2016, and was replaced by Neil Gorsuch earlier this year. Scalia used his dissent in the Supreme Court’s ruling that legalised gay marriage in June 2015 to describe judicial overreach as robbing ‘the people of the most important liberty they asserted in the Declaration of Independence and won in the revolution of 1776: the freedom to govern themselves’.

The fact that the American people’s immigration policy has been determined by nine judges of the Supreme Court, rather than the elected president, should concern anyone who cares about democracy. The question is, of course, made more complicated by the use of executive orders. There is an argument that they are undemocratic, allowing the president to make law without bothering with Congress. But the president can at least be held accountable by the electorate. This is not the case for Supreme Court justices. It is through the ballot box, rather than the courtroom, that Trump’s policies should be judged.

The travel ban is inhumane and arbitrary. But whatever you think of the substance of the policy, judges should not be free to block laws from being enacted and then rewrite them entirely. The questions this ruling raises about the nature of American democracy will no doubt persist longer than 90 days.

Luke Gittos is law editor at spiked and author of Why Rape Culture is a Dangerous Myth: From Steubenville to Ched Evans. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Picture by: Getty

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.