JFK and the paranoid style

The new release of files will only fuel conspiracy theories.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

President Trump’s authorised release of the Secret Service papers related to President John F Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 tells us more about the paranoid style of American politics than it does about the event itself.

Lee Harvey Oswald shot the very popular and photogenic JFK on 22 November 1963. Shortly after he was arrested, Oswald himself was shot by nightclub owner Jack Ruby. The surprising course of events gave rise to a burgeoning mass of conspiracy theories about who was ‘behind’ the assassination. The sense of despair over JFK’s death was only amplified by the assassination four years later of his handsome younger brother Bobby at the hands of the Palestinian activist Sirhan Sirhan.

President Trump’s publication of the Secret Service files on the Kennedy assassination (and its aftermath) is a popular move for many that support him, who are prone to think of political events as a conspiracy by the politicians and mainstream media, all ganging up to stop Americans finding out ‘the Truth’.

The initial view on the assassination was that it was most likely commissioned by the Soviet Union. There seemed to be good grounds for thinking so. Oswald was very left-wing, and had even lived in the Soviet Union for a while. He was active in campaigns of solidarity with the revolutionary regime of Fidel Castro in Cuba.

But tempting as that might be as an explanation, it just was not exciting enough for those fixated on the assassination. In its place, another, wilder, conspiracy theory was promoted by New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison, and popularised by filmmaker Oliver Stone, who based his blockbuster JFK on Garrison’s campaign.

In this account, Kennedy was assassinated by the CIA, with the collusion of the Mafia (who ‘controlled’ Jack Ruby) and the expatriate Cuban mob. Their motives, in this account, were to stop Kennedy’s secret plan to pull America out of the Vietnam War and make peace with Cuba.

Stone’s film was a sideshow of conspiracy theorists and their fantasy of elite collusion against a popular president. The retrospective lionisation of the lost leader made him a touchstone of political rectitude to left and right alike. In the campaign to elect Bill Clinton in 1992, his team found and used a grainy shot of Kennedy shaking the young cub scout Bill’s hand, a metaphorical handing on of the baton.

But historian (and linguist) Noam Chomsky blew apart the Garrison/Stone version when the film came out in his little book about the Kennedy administration, Rethinking Camelot. Chomsky shows that there was no evidence that Kennedy had any intention of withdrawing from Vietnam – at least not until the Viet Cong had been obliterated.

Chomsky explains that the Kennedy of Stone’s imagination – an anti-war liberal held captive by the military-industrial complex – is a fantasy. Kennedy was indeed, as has been demonstrated again in the newer revelations, a deeply belligerent champion of US dominance.

Oswald himself was not a patsy of the CIA. He was a left-winger, not attached to the mainstream Communist International, but on the fringes of the New Left, and perhaps a little unbalanced. At the time, the left felt under pressure from the associations with Oswald, and reacted in different ways.

The anarchist newspaper Freedom carried the headline ‘So What!’ in the wake of JFK’s death, which was in keeping with their indifference to political leaders. Malcolm X said that the assassinations were a case of ‘the chickens coming home to roost’ – meaning that the violence of US society would inevitably rebound upon its leaders. He had a point, but in the end it was a cowardly and sideways justification for the assassination (like the later ‘blowback’ theory of Islamic terror). And all the more so since Malcolm X himself fell victim to the wave of assassinations that swept the country. The Rolling Stones answered the question ‘Who killed the Kennedys’ with the line, ‘After all, it was you and me’.

The journalist Alexander Cockburn, who did most to debunk the conspiracy theory, thought that Oswald did it alone, and that he had a point, considering Kennedy’s vicious treatment of Cuba and Vietnam.

One thing that is underscored in the subsequent history is that assassination is a poor way to change a culture for the better, almost always leading to repression and confusion, because it substitutes the individual will for the popular campaign.

Sadly, the paranoid style of American politics is unlikely to be abated by the publication of this additional material. All it will do is add to the mass of detail on to which paranoiacs project their fantasies. This is largely a reflection of the fractious nature of US politics, and the growing sense of frustration on all sides that they have somehow been robbed of their authority.

This is as true of those Trump supporters who persuaded themselves that there was a secret paedophile ring run by Hillary Clinton as it is of those Clinton supporters donning their tinfoil hats to repel the microwaves being beamed from the Russian embassy.

James Heartfield’s history of The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society is published by Hurst Books.

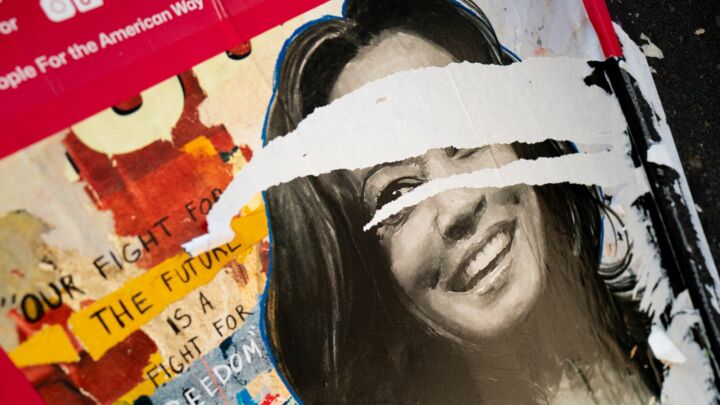

Picture by: Getty Images.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.