Why they love baiting the Russian bear

The West’s anti-Russia rhetoric is becoming dangerously inflamed.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Judging from all the talk about the threat Russia poses to world peace, it can only be a matter of time before the new cold war turns into a hot one. And yet I find myself more worried about the hysterical anti-Russian rhetoric that now dominates the Western media landscape than I am about the supposed military and political threat Russia represents. And I say this as someone who bears a 62-year grudge against the Russian military and its tanks that destroyed the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and forced my family to flee to the West.

I have no doubts that the Russian state is not interested in the cause of humanity. The Kremlin, like other powerful governments, is in the business of pursuing its narrow national and geopolitical interests. Its statements are no more to be trusted than the propaganda spewed out by other governments’ public-relations agencies.

In this respect, Russia’s behaviour is not qualitatively different to that of many other states. So the interesting question is this: how did post-Stalinist Russia become such a hate figure for many in the West? How did a government that behaves like other governments become an entity against which various Western forces, of all shades of opinion, have enthusiastically united?

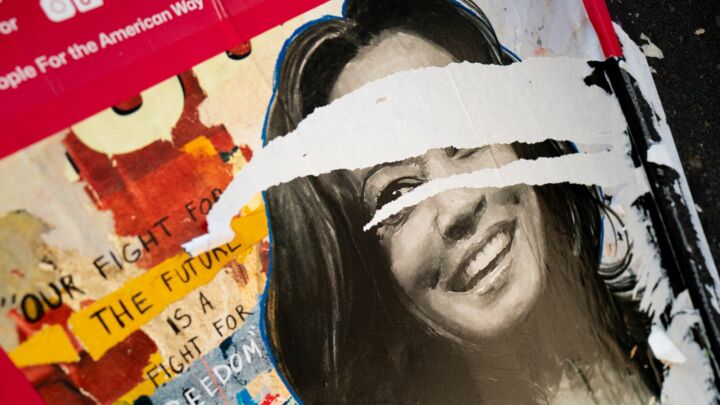

Russia is continually accused of interfering in and influencing or corrupting elections in numerous Western nations. The fantasy that Russian manipulation has directly influenced the outcome of elections has become a kind of self-evident truth. When, last week, a dozen Russians and three companies were indicted for interfering in the 2016 US presidential elections, much of the media said this was a vindication of their suspicions that Moscow exercises a nefarious influence over American political life. Apparently these Russians were equal-opportunity operatives: they reportedly tried to help candidates of all persuasions, from Bernie Sanders to Green Party candidate Jill Stein, all the way to Donald Trump.

For all the publicity surrounding this indictment, no one has been able to disclose whether the Russian propaganda machine actually inflicted any damage on the American democratic process. Whatever the answer to this question, this affair certainly does not warrant the over-the-top reaction of allegedly liberal news outlets like the New York Times. Taking a swipe at both Trump and Russia, an NYT headline warned: ‘Trump’s conspicuous silence leaves a struggle against Russia without a leader.’ A struggle? What struggle? Or are we back to the old Cold War narrative of an ongoing struggle for the free world?

The NYT’s rhetoric was designed to imply that at a time when the future of America’s democratic institutions is at stake, Trump is behaving as a latter-day appeaser: ‘In 13 months in office, Mr Trump has made little if any public effort to rally the nation to confront Moscow for its intrusion or to defend democratic institutions against continued disruption.’ The paper’s call on the president to ‘rally the nation to confront Moscow’ comes off as a poor man’s version of Cold War propaganda. Suddenly, Russians messing around on social media has become the online equivalent of an invasion by Spetsnaz.

Unfortunately, anti-Russian rhetoric is not confined to a poorly informed American media or Washington activists keen to use this issue to score party-political points. Leading French, German and British politicians have played the anti-Russia card, too. The Swedish government has even issued a public-information manual to its citizens on what to do in case of war with Russia.

At times, the intemperate language hurled at Russia becomes dangerously war-like. It is dangerous because it frequently suggests that Russia’s foreign policy has become so malevolent, such a problem for Western interests, that a military conflict cannot be ruled out. Last month, the head of the British Army, General Sir Nick Carter, helpfully reminded the public that ‘Russia is the biggest threat to the UK since [the] Cold War’. He also decided to inform us that Russia ‘would beat’ the UK in a war.

His statements were relatively restrained in comparison with those of the British defence secretary, Gavin Williamson. In December, Williamson said Russia is ‘fighting a war against Britain’ on many fronts. ‘We are in a cool war’, he said, ‘but one where Russia is incredibly active in trying to do damage to British interests’. In recent weeks, numerous experts have gone on record to outline the threat Russia allegedly poses to Britain’s infrastructure, cyber-security, business interests and geopolitical influence.

It is difficult to understand why so many leading commentators, politicians and experts are determined to evoke the ghosts of the Cold War. No doubt the Russian elites can be ruthless in promoting their interests both at home and abroad. The Russian state’s authoritarian temper and illiberal outlook has an impact around the world. Russia’s foreign policy has enjoyed some successes, such as outmanoeuvring Western powers in Syria. But Russia remains, fundamentally, a defensive, status-quo power. In Syria it got lucky. It was the beneficiary of the incompetence and incoherence of Western power in that region. Sure, the Kremlin may dream about reconstituting the old Empire, but in truth it faces enormous political and economic challenges even in its maintenance of the status quo.

Russia’s ambition is to maintain its sphere of influence. And in this respect it is no different to any other major geopolitical player. Nor is Russia the only power that spies on its neighbours and political competitors. The real danger today is that the incessant escalation of anti-Russian propaganda will increase tensions and create the climate for inter-state conflict. The new anti-Russian Cold War warriors are playing with fire; they should be careful what they wish for. Petty posturing in international relations carries far greater risks than it does in the domestic realm – it can unleash a chain of events that all parties may live to regret.

The baiting of the Russian Bear has become bound up with the vying for influence and power in the domestic realm of the West itself. In the US in particular, Russia is used as an all-purpose target in political and public-relations clashes between the parties. Paradoxically, Western observers’ perpetual focus on the Russian threat to Western democracy reveals their own lack of confidence in that democracy. It exposes their declining faith in the political maturity of their own citizens. After all, if a handful of Russian trolls can have such a decisive impact on the political life of a democratic society, then what hope is there for the future?

Frank Furedi is a sociologist and commentator. His latest book, Populism And The Culture Wars In Europe: The Conflict Of Values Between Hungary and the EU, is published by Routledge. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.