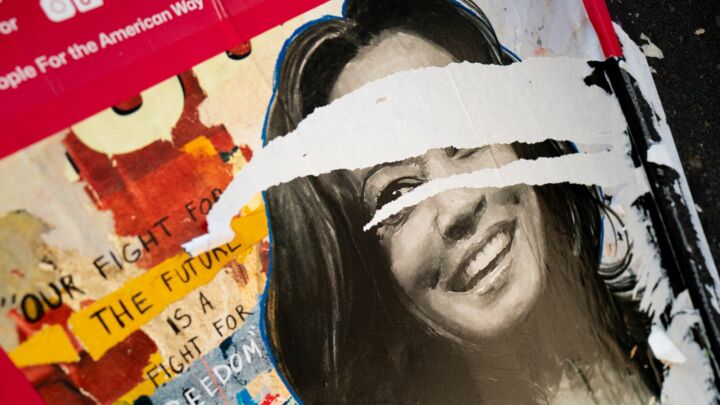

‘We need to think of ourselves as Americans’

Sheri Berman on how identity politics harms democracy.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Steve Bannon, Donald Trump’s former campaign strategist, has said that, during the election campaign, whenever the Democrats played identity politics, he knew Trump was winning. If he’s right, then Trump could well sail into a second term. Since the election, identity politics has continued to be the lens through which many battles in American society are argued over and understood. So, though identity politics has become associated with the left, is it doing the left more harm than good? To find out more, spiked caught up with Sheri Berman, professor of political science at Barnard College, Columbia University.

spiked: Steve Bannon famously said that he ‘can’t get enough’ of the left’s race-identity politics — what did he mean by this?

Sheri Berman: Presumably, what he meant was that, during the campaign, the more the left talked about race, the more his particular base was activated, mobilised and involved. And he also, presumably, believed that it would help to divide Democrats, because they have a much more diverse coalition than do the Republicans. Bannon felt that a lot of emphasis on cultural issues and identity issues, as opposed to problems that bridge these divides, like economic problems, would cause some people to be more activated and more engaged than others. He loved it when Democrats made numerous appeals to a variety of different groups, because he hoped that this would piss off enough of his supporters to get them to the polls, and participating in politics in other ways.

spiked: You’ve argued that identity politics can be particularly destructive for the left. How so?

Berman: Over the past generation the Republican Party has become a fairly homogenous party. It is dominated very heavily by white voters who are not in major metropolitan areas, who tend to be more culturally or socially conservative, who are often quite religious and are, in their political views, quite conservative. And so that’s a relatively homogenous group, and it’s a much larger percentage of the Republican Party than any one group is of the Democratic Party. So it is much easier for someone like Bannon to craft a single appeal that will activate them than it is for Democrats who have a much larger variety of groups – groups who have some overlapping interests, but also some interests that they do not share.

spiked: Do we misunderstand political developments if we see them through the lens of identity politics? For instance, Trump’s election is widely seen as a ‘whitelash’, as a product of unreconstructed racism, even though a significant portion of his voters also voted for Obama twice…

Berman: On some level, there has clearly been a backlash since 2016. The very fact that Trump was elected and has used these coded and often not-so-coded appeals to mobilise his voters has, I believe, increased not only divisions within American society, but also the prevalence or acceptability of certain kinds of views. He’s activated certains kinds of prejudices and certain kinds of biases.

However, if you look at the numbers overall, over the long term in particular, levels of racism in American society have gone down really dramatically. And so elites, and in particular the president, who, obviously, has a huge platform, really have the ability to shape the conversation in terms of what is seen as legitimate and what is not. But the long-term, secular trends were actually going in the right direction – not quickly enough, certainly not extensively enough, but definitely in the right direction.

spiked: When politics is divided up along identity lines, can that obscure the real divisions, and real commonalities, that people have politically?

Berman: Yeah, absolutely. In the United States, over the past generation, we’ve seen this kind of incredible sorting process. As I mentioned earlier, the Republican Party in particular has become more homogenous over time in a whole variety of ways. And so you have fewer cross-cutting cleavages. So, in a previous era, for instance, you would have had southern conservatives and northern liberals in the Democratic Party. You would have had a Republican Party that had conservatives but also some northerners who were much more liberal on economic and, to some degree, social issues. Now that’s much less the case. And that’s very dangerous because it makes compromise more difficult, it makes it much easier to see your opponent as very distinct from yourself and much more threatening. And it becomes much more difficult to play the democratic game, because there are far fewer points of overlap, there are far fewer opportunities for compromise.

spiked: Does this also undermine social solidarity?

Berman: Absolutely. The diminishment of cross-cutting cleavages has encouraged politicians to sow divisions, to make them even deeper, to play off them. In political science, we used to call this, in developing countries, ‘ethnic outbidding’ – politicians mobilising their voters on the basis of identities that they surely had, but were not necessarily the most salient part of their public lives or how they thought about politics. It’s a cheap and easy way to get voters, to mobilise them on these identities and in particular to mobilise them around emotional appeals and fear-based appeals. Fear is an extremely powerful motivator, and it tends to override a lot of other things.

spiked: Do we need to return to a more universal politics?

Berman: Well, it would be nice if we could think of ourselves as Americans as opposed to Democrats and Republicans, or African-Americans and white Americans, or minorities and minorities. Clearly, for a country to function well, we have to feel like we’re in this together. And everybody has to feel like the rules of the game are not biased against them. It is very hard for democracy to work if every time you have an election, if every time you have a political choice, you think that the stakes are so high that you can’t afford to lose. We need to have some sense of ourselves as Americans who have a commitment to certain shared values and institutions and procedures for our democracy to be able to function well at all.

Sheri Berman was talking to Fraser Myers.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.