There is no ‘appeasement’ of China

On the 80th anniversary of Dunkirk, we should remember not to dress up today's conflicts in the politics of the past.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Britain’s debate about the Covid-19 pandemic has a subterranean aspect that has largely gone unnoticed. It relates to China and the idea of appeasement.

Many accuse Boris Johnson’s government of being unprepared for the virus, and weak in tackling it. And so, partly in response to such criticism, Johnson now wants to show grit by reducing the UK’s dependence on China as a source of important goods – and not just medical ones. In other words, Johnson wants to reorientate UK manufacturing and supply chains away from China. According to one report, he also wants to reduce and ultimately, by 2023, eliminate China’s involvement in UK infrastructure, and especially Huawei’s in 5G telecommunications.

The message from the government is simple: it is saying that it might have been guilty of appeasement of the virus in the past, but it won’t make the same mistake again with another, bigger, longer-term threat – China.

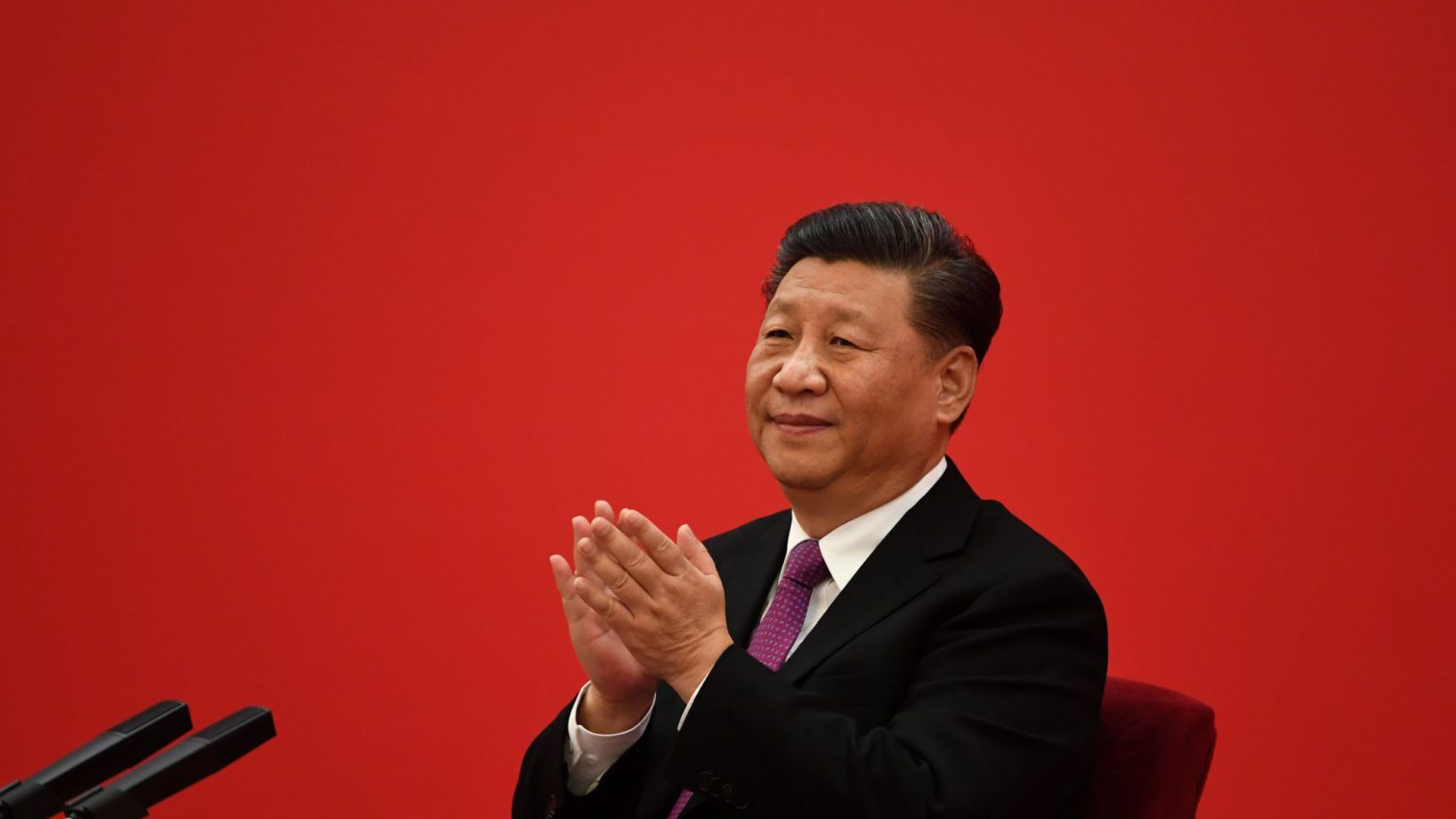

This message is timely, for this week marks the 80th anniversary of the Dunkirk evacuation, in which 338,000 British, French and Allied troops had to be rescued from Nazi forces gathered round, and in the skies above, Dunkirk, on the northern coast of France. The evacuation of Dunkirk was widely seen as the bitter fruit of prime minister Neville Chamberlain’s policy of appeasing Adolf Hitler. So with this anniversary in mind, Johnson, a Churchillian, has had little choice but to fasten upon the myth created around his hero’s opposition to appeasement, and portray himself as an early, principled and courageous opponent of appeasement, in this case of Chinese president Xi Jinping.

There is no shortage of right-wing critics of the seeming appeasement of China. The desire to take steps against Beijing, Tory Lord Patten tells us, now unites ‘both the right and left of the Conservative Party’. An article in the Conservative Woman similarly denounces the ‘appeasement of China that runs through the UK’s political, civil service and security establishments’. For Charles Moore at the Telegraph, Johnson is edging slowly away from Beijing and ‘what some call “authoritarian tech”’.

So should China be quarantined? To get an answer, it’s vital to understand something of what appeasement and Dunkirk were all about.

Not long after British prime minister Neville Chamberlain conceded control of Czechoslovakia to Hitler in the Munich Agreement of 1938, the dangers of appeasing mortal adversaries became a staple part of Britain’s national political discourse. In particular, after retreat and rescue at Dunkirk, the fatal consequences of being unprepared for the enemy suggested that appeasement of a foreign menace would always bring disaster in its wake.

Now as James Heartfield has shown, the real, military evacuation of Dunkirk had little in common with the myth of mass civilian heroism promoted by JB Priestley and accepted ever since. To invoke the Dunkirk spirit today, against Covid, is therefore a mistake.

Far less contentious than the myth of the Dunkirk spirit is the view of appeasement put forward in Guilty Men, a bestseller written under the pseudonym ‘Cato’, and published in July 1940 (1). Indicting a rogues’ gallery of politicians, of every stripe, for appeasing Hitler, Guilty Men was put together by Labour Party journalist and left-wing firebrand Michael Foot, as well as by Foot’s Liberal editor at the Evening Standard and a Tory hack on the Daily Express. It opened with the beaches of Dunkirk and the plight of what it described as The Doomed Army there.

From that point on, the book attacked three previous prime ministers: Ramsay MacDonald, Stanley Baldwin and, above all, Chamberlain. The last had taken Hitler at his word, and, on 30 September 1938, had signed a piece of paper at Munich giving away Czechoslovakia to the Nazis. ‘Chamberlain’, wrote the authors of Guilty Men, ‘trusted Hitler’.

‘Ever since Munich, [government ministers] had been assuring the public that they were ready, aye, ready now for the war which was never going to come’, wrote Foot et al. Yet ‘the state of armaments of the British Expeditionary Force stranded on the blood-soaked dunes of Dunkirk’ more than a year later showed that readiness had proved a mirage. Indeed, even after Hitler completed his takeover of the Czech regions of Czechoslovakia on 15 March 1939, the appeasement of Hitler, though dead, ‘still took some 15 days to lie down’. And after that, 16 months had gone by, only for government sloth and inefficiency to deny Britain’s footsore soldiers the tanks and fighter aircraft that could have reversed their fortunes at Dunkirk.

This diatribe against the appeasers had a simple message. Apart from some honourable exceptions, such as Churchill, the Tories, Guilty Men argued, should have armed the nation against Germany earlier, and been more ruthless with Berlin.

Perhaps so. But to cast Johnson as a Chamberlain bungling before the virus, or for acting too slowly against China, for fear of causing offence and a cut-off in PPE supplies, is foolish.

First, it is to draw an inadmissible historical parallel between the domestic repressions and international designs of Beijing today – severe measures in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, serious influence in Africa and elsewhere – and those of Nazi Germany eight decades ago. Such a parallel rules out of the picture the unique historical experience of the Holocaust, and the six million Jews who died in it. We cannot do that, any more than we can pass over the great famine that Mao presided over in the middle of the so-called Great Leap Forward years of 1958-62.

Second, various elite forces in British society invoked appeasement and Munich as grounds for the Falklands War against Argentina’s General Leopoldo Galtieri, and as grounds for the destruction of Iraq’s Saddam Hussein in two Gulf wars. In this they have often followed glib, right-wing American narratives about Munich; and even today, in Canada, we find the Conservative leader Andrew Scheer denouncing Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government for its appeasement of the Chinese regime.

Those who want to boycott China are not just unrealistic, given the clout China has, and the difficulty a heavily globalised economy such as Britain’s is bound to have in disentangling itself from the workshop of the world. The boycotters are bent, too, on pursuing measures that can all too easily escalate from economic to military ones, such as counter-manoeuvres against China’s own manoeuvres in the East and South China Seas, and elsewhere.

A crusade against appeasement soon turns into just that: a crusade. One need not be a fan of the Chinese Communist Party or the Democratic Party in the US to ask: do we really want to join with President Donald Trump in that crusade?

We should refuse that course out of courage, not out of fear of retaliation by Xi Jinping. We should refuse it because, in the 2020s, we will find our own methods of showing solidarity with China’s population. In their reckless historical amnesia about appeasement, Boris and the Tory right would like us to subordinate negotiations with China to their agenda. Nothing good will come of that.

James Woudhuysen is visiting professor of forecasting and innovation at London South Bank University. He is also editor of Big Potatoes: the London Manifesto for Innovation. Read his blog here.

Picture by: Getty.

(1) Guilty Men, by Cato, Gollancz, 1940

Spare a fiver, support spiked

Become a £5 per month donor today!

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.