‘I am free to write exactly what I want’

Roddy Doyle talks writing, whiteness and what it means to be Irish.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

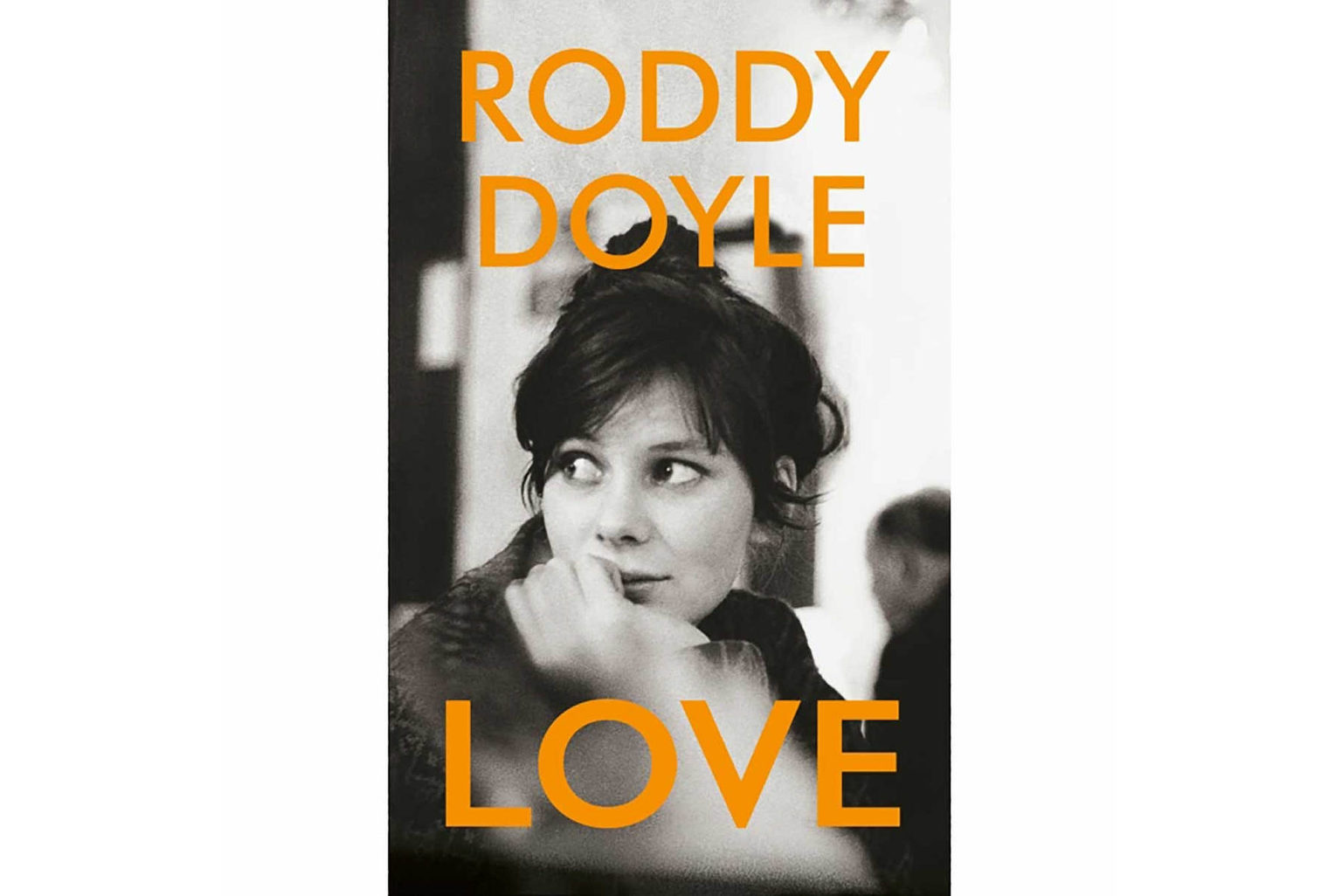

From his 1987 breakthrough novel The Commitments and the Booker Prize-winning Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha through to more recent work, such as Smile and the Two Pints series, Roddy Doyle’s work has always been soaked in the atmosphere of his native Dublin. His latest novel, Love, is no exception. Brimful with banter, booze and not a little melancholy, it explores the friendship of two middle-aged men, Joe and Davy, as they re-examine their lives and loves during a long night of the pub soul. And, as ever with Doyle’s work, out of the mundanity, something profound emerges.

Ella Whelan caught up with Roddy late last year, to talk Love, a changing Ireland and life under lockdown.

Whelan: In Love, you return to the scene of two men in the pub that you have explored in several other recent stories – I’m thinking of the Two Pints series. At the risk of sounding crass, that means you are spending a huge amount of time focusing on possibly the most unfashionable character type these days – the middle-aged white guy. How are you getting away with it?

Doyle: [Laughs] It’s interesting. They are middle-aged, if not more than that. They’re on the cusp of elderly, and they are white men. But there’s an extra part that has to be added, I think – and that’s that they’re Irish.

When I hear Irish people using the term ‘white men’, I always think, don’t forget your own colonial past, you know? Yeah, we’ve got the pigmentation or the colour. But we were colonised. The history is different. I do feel being Irish is different than being English, or white American or whatever. It’s not to exclude the whiteness – obviously, that’s there. But 20 years ago, that statement, ‘white man in Ireland’, would have had no meaning whatsoever. Because 99.99 per cent of the male population was going to be white. It’s only recently that you can point to Irish people and say, they’re Irish, but they’re black or Asian. And that’s a very recent thing.

It’s not that I feel immune to [the accusation of focusing on white men]. But, when I’m having literary discussions, I feel I have to remind people that I’m in Dublin, actually. Does that make sense?

Whelan: It does.

Doyle: And also, even if I was in London or wherever, my life is my material. It’s my research in a lot of ways; growing older, changes in Ireland that are pretty spectacular. Also, what’s happening over the past nine months, in terms of lockdowns, and things like this. So it’s by observing this and living this that I have material to write about. So, in a way, I’m stuck in that I am a white man in his late middle years. And I can never pretend otherwise. So either I stop writing altogether, or I just keep on doing what I do, and try to do it as well as I can.

Whelan: You mention the spectacular changes in Ireland over the past few decades, from the rise and fall of the Celtic Tiger to the cultural and political shifts – the referenda on same-sex marriage, and on abortion and so on. But have the people actually changed? Have the two men in Two Pints or even Love actually changed? When they go back home and shut the door in their Northside houses, are they the same?

Doyle: Good question. But you’re asking me to go past what’s in the book, you know. I’m often asked, for example, what happened to Paddy in Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha after the story finishes. And I haven’t a clue. Once the book is finished, I’ve lost all interest in them. And it’s the same with all books.

But I do think it’s quite clear that there have been fundamental shifts and changes in Ireland, you know. People’s attitudes have changed towards gay people, for example. My mother was alive when that referendum came up and she voted in favour of same-sex marriage. Myself and one of my sisters were laughing about it that weekend. My mum said to us, ‘I’ve always liked the gays’. And the difference was that she was only able to say that out loud in the last 20 years of her life, possibly. And the previous 20 years, she probably couldn’t have said that out loud. And the 20 years before that, she might not have been aware of what that would have meant.

I do remember my parents talking about what often were called ‘characters’ and the parts of Dublin they came from. It was quite clear they were talking about men dressing as women. But they were ‘characters’, and they were kind of tolerated – they were a part of the urban landscape. No mention of their sexual leanings or anything like that. So it’s a strange, contradictory one. So I think what happened, what has certainly happened in my lifetime, is that people have license to say out loud things that might never have been said out loud before.

Whelan: You say that people can say a lot more now than they used to. But there’s also a desire not to cause offence. And so that means people are less able to say things, too. That’s interesting, because one of the joys of your writing is the dialogue and humour –it’s loaded with affection, of course, but it can be cruel. Do you think some of that is getting lost in the desire to avoid causing offence?

Doyle: It’s a good question. I think what’s behind the comedy in Two Pints is that it has two men who are trying to retain their sense of identity as heterosexual men of a certain age reared in a certain way and still be tolerant at the same time. And I suppose you seem to be suggesting that if you’re tolerant, there’s a certain intolerance in trying to be tolerant insofar as there are things you can’t say anymore.

Whelan: Exactly. In Love, the characters keep checking each other and then apologising. There’s a real nervousness to their interactions.

Doyle: Well, in part, it’s because, even though they’re old friends, they don’t know each other very well anymore. And the shortcuts they used to be able to take when they were inseparable in their early 20s, they can’t take those shortcuts anymore. It’s a change, it’s different.

Do I recognise myself in that? I don’t know. Do you know, I’m meeting a couple of friends of mine. I’d normally meet them in a pub, but I haven’t been able to meet them in a pub since March. So we’re meeting in the park for a cup of coffee this afternoon. And we can have a conversation as free as we want to because we have known one another since we were children. And we know what our attitudes and our feelings and our views, political, moral, social, are. We know our histories, so to speak – what’s gone right and what’s gone wrong. So we can use the shorthand of friendship, and we can use language that we might not use with people we don’t know as well. We can crack jokes that we know are ironic – and there’s not a pair of ears gonna be listening to us and taking a literal interpretation of what we say. So there’s a freedom in what we can say. And I think the two lads in the pub have that freedom as well. They can say what they want.

I don’t worry too much. I think I have freedom to write exactly what I want. But it has to be within the context of what I’m doing and who the characters are and what they’re saying. So I understand what you’re saying and what you’re asking. But when I’m writing a story, as I have been this morning, for example, you’re within the limit of the story, if that makes sense. And these are curtailments, you know. So I go into, say, a Two Pints thing in the knowledge that I can get them to say exactly what I want. But I do recognise that if I use certain words now it can just be a distraction.

Whelan: Love seems to explore the intimacy between these two men and their ability to be able to talk about intimate things, about love and sex. Which is remarkable when you consider how ubiquitous sex seems to be today.

Doyle: That’s a good point. I didn’t go into the whole notion of Tinder – it’s a world I don’t know. It doesn’t come up in conversation with my friends anyway. We don’t look at people 20, 30 years younger than us, you know, and envy them or whatever.

But I do know that as young men going back to when I was in school with the Christian Brothers, and even at home, we were not trained to consider women as friends. We weren’t trained in any sense that intimate conversations were somehow a good thing or a possibility. And the two main characters, Joe and Davey, are trying to, in a way, scale a wall. I know, Joe uses the image of the wall from that movie, Stardust. But they are trying to scale a lot of barriers that they feel like they’ve grown up with – particularly Davey, who grew up in a silent house.

With my own parents, it was clear that they liked and loved each other very much. They both lived into their nineties and had each other for most of the time. And they held hands, for example, right into their eighties when they were walking together. And they made each other laugh. They were good companions.

But they never ever, either of them, spoke to me about sex. When I was a teenager, for example, they never noticed either the mechanics of it, or the bit beyond the mechanics of it. If you had a girlfriend, my dad never spoke to me about how to behave with a girlfriend. My mother never did that either. And we never had sex education in school. Nothing. So we were kind of thrown into the pit – as people were for thousands of years before us. But what I’m saying is that women could chat about intimate things and men didn’t. So what I tried to do with Love or the Two Pints men is to get beyond the football and what’s on telly and the politics, you know, global politics. And into the odd revelation, the odd, intimate thing.

I say this half joking, but I think it’s half true, that if they were younger men, Love would be a much shorter book – it would probably be a short story. I think they’d be more confident about talking about intimate things. They wouldn’t be as choked. So that’s why the Love characters think they need the alcohol, actually, to fuel the conversation. And then, of course, so much bullshit gets spoken so sincerely when people are pissed that it then becomes a novel.

Whelan: In Love, Davey desperately wants Joe not think of him as the one who left Ireland to live in England. All that tension you mentioned regarding Ireland’s colonial past is just slightly under the surface there. I get it when I go back to visit my family in Ireland — you feel very conscious of people calling you a blow-in. Did you have that sort of conflict going on in your head when you were writing the two of them?

Doyle: I chose Wantage for Davey’s English home, because my wife and I went on this great walking holiday there some years ago. It was really brilliant. We’d been going to kind of little villages and pubs and stuff for that week, and then into Wantage on a Saturday night. And it was nice to be surrounded by people for the first time in a week. On the other hand, Jesus, I wouldn’t want to live here, you know.

So this is the thing when you’re writing fiction, you can plant your characters exactly where you don’t want to be. So that’s where he lives – in Wantage. Almost literally in the middle of England, isn’t it? And he talks to Joe about getting used to the names, which seem weird at first, and things like that.

I have three siblings – so that was four children in our family house – and when we all grew up, there was a 10-year period where I was the only one who lived in Ireland. The others worked abroad. And they all came – for want of a better word – home, during the mid-1990s when things were picking up, so to speak. But there was always that family dynamic. Somebody would come home and they’d start talking about London, and you’d think ‘ah fuck you, and your London – what do they have that we don’t have here?’. That type of thing, you know? And it was always the excitement, and the notion of the return of the yank. And I was always aware of it.

Davey, he loves taking out the Dublin words. And as he gets drunker the Dublin accent comes out, and the two of them become kind of wizened versions of their earlier selves. But he loves taking out words like ‘grand’ and things like that. He can use words that he ordinarily wouldn’t use when he’s across in England. There’s a guy I went to school with called Mick, and he emigrated and became Mike, you know, that way. And when he comes home again, he’s Mick. So you’re on the borderline, I suppose, from a writing point of view. It’s brilliant, because you’re on top of a wall, and you’re looking into two different gardens. But I suppose if you’re living that life, you’re kind of wondering which garden is your own?

Are you familiar with the Irish short story writer Maeve Brennan?

Whelan: No.

Doyle: She’s brilliant – particularly the stories set in Dublin. She moved to America with her family when she was a teenager. And she wrote an awful lot of her stories for the New Yorker. I was just rereading some of them recently, and in the ones set in America, you can tell she doesn’t like those characters. The stories really come to life when she goes down to the kitchen, where the Irish Americans are. So although she’s writing for the New Yorker, and she was blue, beautiful and very glamorous, and fitted in perfectly with that Metropolitan New York life… even though she belonged to the world, above stairs, so to speak, it’s when she’s writing the dialogue of the Irish servants that the stories take on a really incredible life. It’s amazing. And I think that makes her work better. Because she’s both an immigrant and not an immigrant, if that makes sense. She’s left and she’s come back.

And I think that Davey has this, too. But the ice is a bit thin as he walks on it. So he has to be careful, because he’s spent more than half his life in England.

Whelan: Your writing always captures a community’s warmth. Even in something like The Woman Who Walked Into Doors. Whatever problems the main character Paula Spencer is facing, there is a kind of network of people who will come to her aid. Likewise, Joe in Love has a big family. There’s a network there. A social solidarity. Do you think that way of life is in peril today? Do you think big trends like globalisation threaten it? Or are you hopeful that it will persist?

Doyle: Is it in peril? Yes, perhaps. Am I hopeful? Yes, I am.

It’s hard to imagine, but in early 2020 there was a General Election in Ireland. And it was a mess in some ways because there are three big parties now: Fine Fail, Fine Gael and Sinn Fein. And then a rake of independents, most of them left-wing – most, but not all. But what emerged quite clearly is that the big issues from the point of view of voters (and there was a big turnout) were the health service and homelessness. There were others, but they were the big issues, and that to me is really hopeful. That people weren’t just thinking about tax. They weren’t voting for the equivalent of Trump because the tax levels would be low. So that to me is a sign of hope.

What happens on the other side of this pandemic, I don’t know. But there has been a certain solidarity here [during the pandemic] anyway. Even in the early days when we were all in this really severe strict lockdown, there was a sense of we’re all doing this together – there was a sense of fairness about it all and a sense of shared experience. I think it’s brought out the best in people in a lot of cases.

Whelan: What of a specific sense of working-class solidarity?

Doyle: It’s there. I’m lucky enough to be involved in a football club — I’m the honorary president of the football club, it’s 50 years old and when I was a little kid I played for it. It’s just a local club, two adult men’s teams and children’s teams and the rest of it. And it’s sustained by the work of the men and women who live in the local area who are the children of men and women who established the club in the first place. These are working-class, lower-middle-class people who are doing this for nothing. People who have no children, people whose children have long grown up and have no skin in the game anymore are doing it.

I’m also involved in an organisation called Fighting Words – trying to encourage children to write creatively. We’ve got branches all over the island in the 32 counties. And we need volunteers, and I worried when we opened up 11 years ago whether we’d get any. But local people signed up in their thousands. Volunteerism is a good sign. And people are just dying to volunteer for things they hope will make the place they’re living in a better place. It’s just visually obvious at weekends around football clubs and other sports clubs. Anything that’s community-based seems to be just thriving. Whether it works in other areas, I don’t know.

But I wouldn’t worry about that. I wouldn’t worry about working-class people looking out for one another… People often look at me slack-jawed when I say these things in Ireland, you know – but culturally and socially and morally, working-class people tend to be a decade or two ahead of everybody else. Working-class attitudes towards gay people were so much more tolerant before it became official, do you know what I mean? And working-class people stopped going to mass and stopped listening to priests decades before. And working-class people decided that the whole concept of illegitimacy was a nonsense decades before the word stopped having any legal meaning. So, I wouldn’t be too worried about working-class people. No.

This interview has been edited for length.

Ella Whelan is a spiked columnist and the author of What Women Want: Fun, Freedom and an End to Feminism.

Love, by Roddy Doyle, is published by Jonathan Cape. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

Pictures, unless otherwise stated, by: Getty. Final picture by: Chris Boland. Visit his site here.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.