The barbarians at the library gates

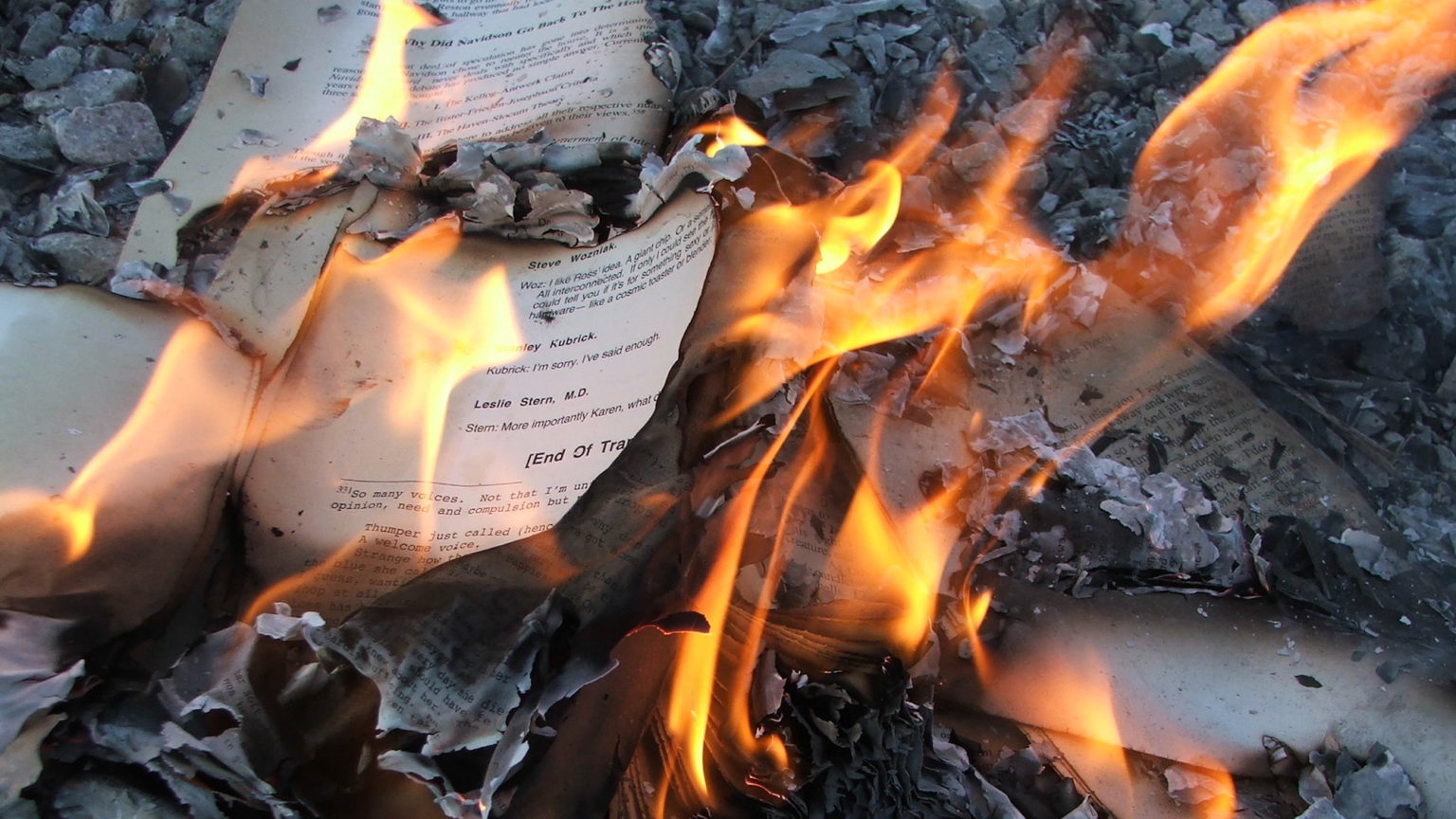

Richard Ovenden's Burning the Books shows why preserving the past is an ongoing struggle.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Richard Ovenden’s Burning the Books serves as a timely reminder of why we need to safeguard and preserve knowledge.

Ovenden knows what he’s talking about. He has been Bodley’s Librarian at the University of Oxford since 2014. Before that he worked at Durham University Library, the House of Lords Library, and many others. So, as you would expect of someone immersed in librarianship, he knows how central libraries have been to the past, present and future of human culture.

Ovenden takes us on a journey through the ages, from the Ancient civilisations of Asia Minor to Nazi Germany, providing a detailed account of various instances of book-burning and library destructions. He notes that people have long possessed an instinct to archive, catalogue and preserve. He backs this contention up with examples from 19th-century excavations at Nimrud and Nineveh, two Ancient Assyrian cities which flourished between 1350 BC and 610 BC. Many of the remains, which included 28,000 clay tablets, featuring much astrological and medical knowledge, were then transferred to the British Museum for further study. This discovery was crucial to understanding how essential the storage and maintenance of the tablets were to the Assyrians.

The near mythical Great Library of Alexandria, in Egypt, was built during the third century BC under the rule of Ptolemy V, and it prompted other rulers to establish their own rival libraries. The largest of which was the Library of Pergamon, founded by King Eumenes II. Both Alexandria and Pergamon even had their top scholars competing with one another, with astronomer and mathematician Aristarchus providing commentary on Hesiod in Alexandria, and Stoic philosopher Crates of Mallos commentating on Homer in Pergamon.

The Library of Pergamon fell into decline during the first century BC under the Roman Empire, while the Library of Alexandria persisted into the third century, until it was finally left to ruin. As Ovendeon pointedly writes of Alexandria:

‘Alexandria is a cautionary tale of the danger of creeping decline, through the underfunding, low prioritisation and general disregard for the institutions that preserve and share knowledge.’

Still, some of the oldest libraries that Ovenden covers remain in existence today, such as the library at the St Catherine’s Monastery, founded in the desert of Sinai in the sixth century.

The 15th and 16th centuries were a truly turbulent time for libraries and books. Which is hardly a surprise. The Reformation devastated many monasteries, which had long provided homes for libraries. But we also read of the heroic endeavours of monks, who would rescue books from endangered monasteries and store them privately, while they hoped and waited for the political situation to stabilise.

Burning the Books would be nothing without Ovenden telling the story of the Bodleian itself. With fondness, he describes the efforts of Sir Thomas Bodley (1545–1613), a fellow of Merton College and a diplomat in Queen Elizabeth I’s court, to rescue and rebuild what was to become known as the Bodleian during the late 16th century. Bodley sacrificed his own money, time and books to help the library flourish, as it still does to this day.

Ovenden also looks at the history of Franz Kafka’s work, and the decision of his best friend and agent Max Brod, who kept and published Kafka’s output posthumously, against Kafka’s wishes. Ovenden is asking a good question: what is more important – the privacy and wishes of the author and his family, or public culture?

Ovenden is an eloquent guide through a tumultuous history, and he has clearly put a tremendous amount of love and research into this project. But, at points, some of the stories can be a little repetitive. An Ancient library is built. Said library gets destroyed. Some people save a portion of the library. And the library gets rebuilt.

Nevertheless, there is plenty to fascinate and inspire here, too. During the Second World War, for instance, we learn of the Jewish archivists, who, facing death in the Warsaw Ghetto, concealed personal documents in metal milk jugs and boxes, in the hope they would later be discovered and bear witness to their suffering during the Holocaust. It makes for a moving testament to the worth and importance of textual knowledge, and the courageous lengths some will go to preserve it.

Ovenden is not only concerned with the more distant past. He also explores the ‘digital deluge’ and attempts, such as that of the Wayback Machine, to preserve the archives of the internet. However, he argues that the ultimate responsibility for the preservation and transmission of knowledge should fall to libraries. And he then calls for more funding to support libraries in shouldering this responsibility.

Ovenden’s argument for the importance of libraries has acquired a new urgency in the context of statue toppling, and the ongoing ‘decolonisation’ of library collections. In this sense, Burning the Books reasserts the importance of preserving our heritage and reconciling with our past, rather than purging and dispensing with it.

Ovenden makes a compelling case. We do need to support our libraries better, financially and politically. Above all, he shows us the importance of preserving our past for the benefit of the future.

Dinah Kolka is a freelance journalist.

Burning the Books: A History of Knowledge Under Attack, by Richard Ovenden, is published by John Murray. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

Picture by: LearningLark, published under a creative-commons licence.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.