The legacy of the Pentagon Papers

They struck an important blow for press freedom, but have also shaped today’s conspiratorial mindset.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Fifty years ago this month, the New York Times began publishing parts of United States-Vietnam Relations, 1945-1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense, otherwise known as the Pentagon Papers.

The Pentagon Papers, which told the inside story of US involvement in Vietnam, were commissioned in 1967 by defence secretary Robert McNamara. He was in despair about the Vietnam War and hoped the study would help future US policymakers avoid their predecessors’ errors. There was never any intention to make the study public.

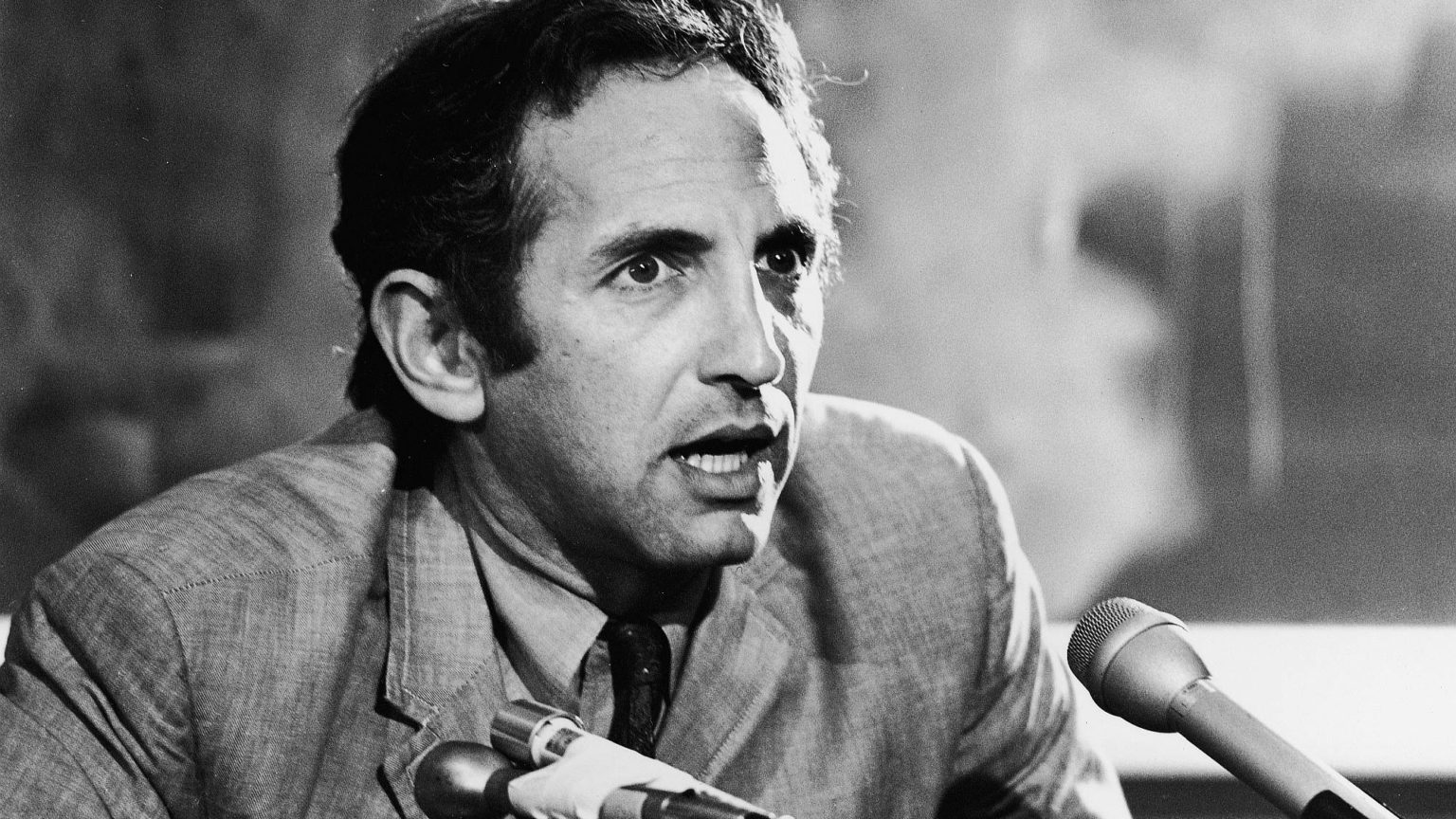

But four years later, Daniel Ellsberg, a department official, decided to leak it to the Times. Its publication caused public outrage, and further undermined public support for the war. And no wonder. As the Times put it in June 1971, the Pentagon Papers showed that policy decisions regarding the war were ‘deliberately distorted or withheld altogether from the public’. McNamara, the man who had commissioned the study, was not surprised by its impact. ‘You know’, he confided to a friend, ‘they could hang people for what’s in there’ (1).

Indeed, the revelations dropped like so many bombs over various administrations, past and present – especially as they showed the US had been intervening in Vietnam’s affairs much earlier than previously thought.

Several successive presidents were implicated. The papers showed how Truman had assisted France in its war against the Viet Minh in the 1940s. They showed how Eisenhower had backed South Vietnam (‘essentially a creation of the United States’), deliberately undermined the Geneva Peace Talks in 1954, and paved the way for South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem to rise to power in 1955. They showed how, under Kennedy, the US military had helped overthrow and assassinate Diem in 1963. And they showed how Johnson had lied about the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964 (which provided the legal rationale for open warfare against North Vietnam). They even showed that Johnson was secretly expanding the war, while telling congress and the public that he was seeking to wind it down.

The revelations didn’t stop there. The papers exposed the lies US presidents and other officials had told Congress and the public about their intentions and the state of the war. The US-backed South Vietnamese government in Saigon was, it turned out, weak and incompetent. And its Communist adversary in the north remained resolute, despite the US’s bombing campaign. American presidents privately doubted the chances of victory. Yet, as the papers revealed, they continued to present a false, optimistic picture to the public, while pouring in ever more money and military firepower.

Thanks to the Pentagon Papers, the US’s intervention in Vietnam was increasingly viewed not only as a mistake, but as immoral, too. Few inside or outside government still had faith in the original objective – to contain the spread of Communism in South East Asia. A memo from the Johnson administration admitted that the main reason for persisting with the war was ‘to avoid a humiliating US defeat (to our reputation as a guarantor)’. That clearly did not justify killing millions of Vietnamese, including civilians. ‘Why should Americans be asked to give their lives to such a cause?’, many asked.

The Pentagon Papers certainly had a profound impact on American politics in the 1970s. But it’s worth asking, 50 years on, what their legacy has been, and whether policymakers and political analysts have drawn the right lessons.

There’s little to suggest the papers had much impact on American foreign policy. They highlighted the US’s many errors and false assumptions, from its belief it had the right to override the self-determination of local people to its failure to understand the complex realities on the ground. Yet, as we’ve seen in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, US policymakers, both Democrat and Republican, continue to make those same mistakes.

The Pentagon Papers have also shaped our understanding of national-security whistleblowers. Ellsberg was a defence analyst and specialist on Vietnam who became disillusioned with the war, and hoped that leaking the study would accelerate its end. He initially offered it to members of congress, but none would touch it. It was only then that he arranged to share the study with Neil Sheehan of the New York Times.

Today, Ellsberg is considered a hero by many contemporary leakers, whistleblowers and journalists who publish state secrets, from Julian Assange to Edward Snowden, both of whom explicitly invoke Ellsberg as an inspiration. But there is nothing heroic or good in itself about revealing state secrets. A degree of confidentiality, especially around national security, is necessary for the running of a state. In the US democratic system, controls on national-security secrets are imposed by congress and the executive – two elected branches of government which are ultimately accountable to the people. Unlike whistleblowers, who are accountable to no one. They willingly allow their personal political convictions to override the democratic process.

Ellsberg arguably conducted himself more responsibly, discreetly and carefully than his successors: he at least attempted to go through congress first, while today’s whistleblowers deliberately work outside of democratic channels; the Pentagon Papers were drawn from an analytical study which concluded the war was unwinnable, whereas today’s whistleblowers steal and publish raw data, memos etc; Ellsberg did not divulge any current state secrets, while Snowden had no qualms about revealing details of ongoing counter-terrorism operations; and Ellsberg understood that he had broken the law, and was prepared to serve prison time, while Snowden fled to Moscow to avoid accountability.

Yet, while Ellsberg’s whistleblowing was arguably of a different nature to that practised by Snowden or Chelsea Manning, it is still linked to it. It is still referenced by contemporary whistleblowers as a precursor and justification for their often indiscriminate efforts to expose the inner workings of government. And Ellsberg himself is happy to endorse and support contemporary whistleblowers. ‘Every attack now made on WikiLeaks and Julian Assange’, he said in 2010, ‘was made against me and the release of the Pentagon Papers at the time’.

This leads us to the most problematic aspect of the Pentagon Papers’ legacy – namely, the extent to which they have helped fuel the conspiratorial mindset now corrupting our political discourse. This may not have been Ellsberg’s intention. But there’s little doubt that the Pentagon Papers have subsequently been used to reinforce and justify the view that it is only by unveiling the machinations of those working behind the scenes that we can really understand political decisions and world events. Or as Assange, who once authored a piece called ‘Government as conspiracy’, put it in 2010, ‘the way to justice is transparency’.

But we don’t always need to see everything behind the scenes. Government is not always a conspiracy. In most situations, what is already in the public domain provides sufficient material from which to draw political conclusions. So, while the Pentagon Papers exposed truths about the Vietnam War it was important the public knew, we didn’t need Chelsea Manning handing over low-level documents to the WikiLeaks crew in 2010 to know that the Iraq War, which began in 2003, was misguided.

More positive is the impact of the Pentagon Papers on press freedom. After the Times started publishing the papers in June 1971, President Nixon sought a court injunction to stop it. The case quickly rose to the Supreme Court, which ruled that the US government had not met the ‘burden of proof’ required under the constitution for prior restraint.

In one sense, the decision was a landmark victory for press freedom. The court established that to prevent the publication of classified information, the government must show that it will ‘surely result in direct, immediate and irreparable damage to the nation or its people’. This set a significant bar for the government to reach. According to James Goodale, the former general counsel and vice-chairman of the Times, this test gave ‘the press far greater rights than what it had before Nixon brought the Pentagon Papers case’.

Beyond the legal implications, the political fallout from the Pentagon Papers case made it hard for the government to limit press disclosures of national-security details. ‘The case created a largely overwhelming sense that the press cannot be either enjoined from or prosecuted for publishing national secrets’, says Geoffrey R Stone, a law professor. ‘That’s become the expectation as a result of the Pentagon Papers’, he adds.

As David Sanger put it in the Times earlier this month, the press is now free to publish secrets in ways ‘that were unimaginable in 1971’. He adds that: ‘Reporting on drone warfare and secret US bases in Africa, on offensive and defensive cyberoperations, on the status of barely secret negotiations with Iran or the Taliban, is now common practice.’

Yet the positive impact of the Pentagon Papers on press freedom arguably owes more to the political and cultural atmosphere they encouraged than the ruling itself. And that favourable atmosphere can change. In recent years, under both Obama and Trump, the Department of Justice has increasingly sought to obtain journalists’ communications and force reporters to reveal their sources. The Pentagon Papers may have struck a blow for press freedom, but the powers that be have long been busy striking back.

So, in sum, the Pentagon Papers certainly played a role in bringing an end to the Vietnam War, and can be considered a triumph for press freedom, but their legacy is mixed. Still, the fact that we are debating their meaning 50 years later is a testament to just how momentous was their publication.

Sean Collins is a writer based in New York. Visit his blog, The American Situation.

(1) Quoted in The Best and the Brightest, by David Halberstam, Ballantine Books, 1992

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.