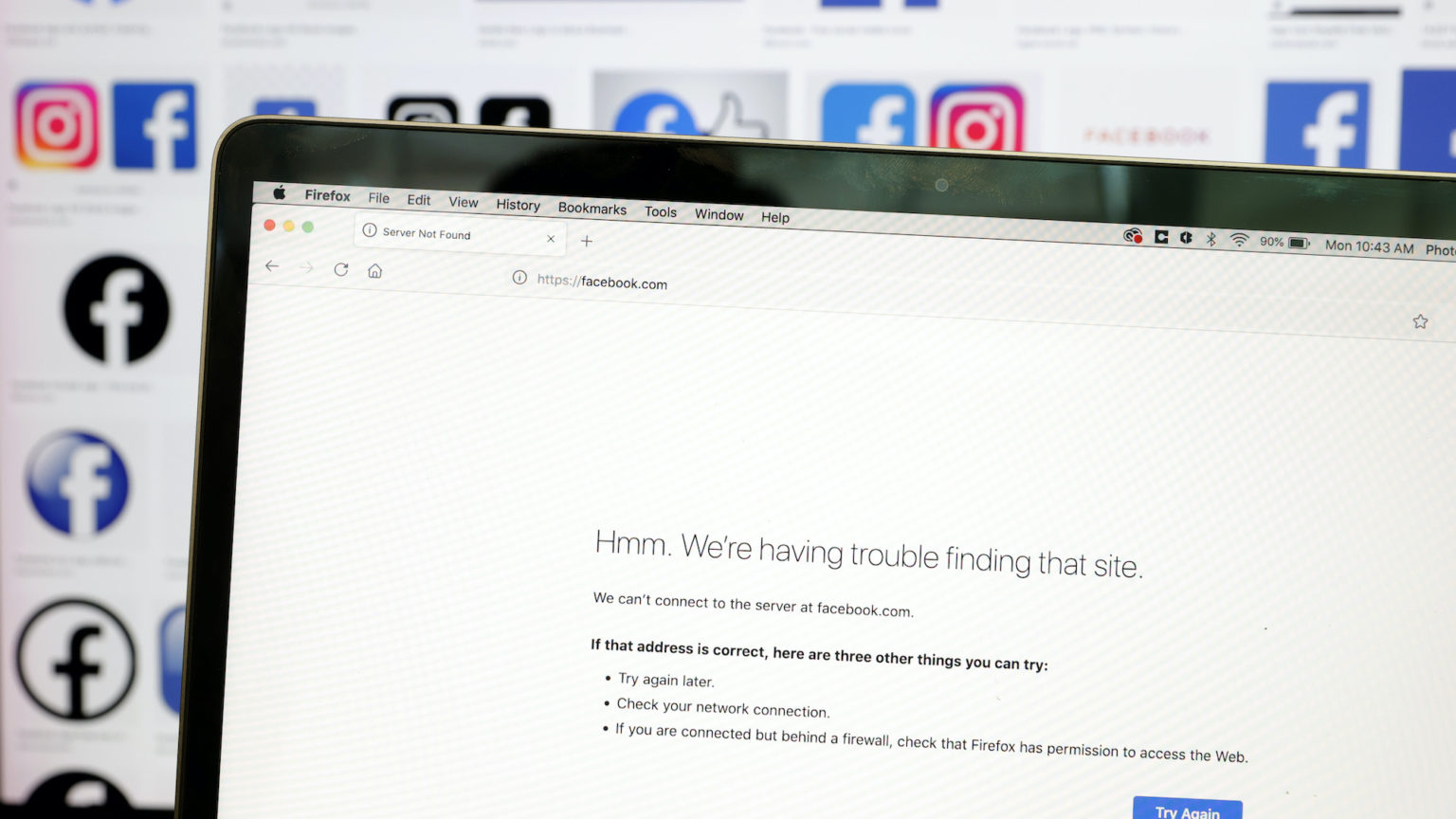

The Facebook outage shows we need to rein in Big Tech

We should never have allowed the tech giants to become so dominant.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Big Tech’s growth has been so unstoppable that at times it seems as if only its own incompetence can halt its rise.

Facebook attributed its six-hour downtime this week to fat-fingered system administrators, rather than to sabotage. It was a reminder of how crude and neglected the internet’s key infrastructure has become. Plans to improve the key protocols remain a bone of geopolitical contention, as the most comprehensive set of improvements has been advanced by China. Other options – as I have previously explained on spiked – lie largely unexamined.

The outage was also a reminder of Facebook’s immense power and reach – especially since Facebook also owns the ubiquitous WhatsApp messaging app, widely used by communities and workplaces, and Instagram.

This has reignited calls for Facebook and the other tech monopolies to be broken up – or at least investigated under competition and antitrust laws. The US has extensive competition powers that remain largely unused against Big Tech. In fact, when Facebook’s stock took a nosedive after the outage, its value fell by a greater amount than Facebook has ever been fined by competition authorities in its entire history.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s hard to dispute that the US’s political reluctance to use its competition powers has played a direct role in the rise of the ‘big five’ tech monopolies – Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google (or FAANG). A decade ago, Microsoft was the only tech firm among the 10 largest global corporations. Today, all of the top five are tech companies. The smallest of the top five, Facebook, is worth more than twice as much as the largest company a decade ago, Exxon.

When Barack Obama was re-elected in 2012, he pulled back from the trust-busting rhetoric of his first term. Around that time, Federal Trade Commission officials concluded that Google had abused its monopoly power and that an antitrust case should be brought against it. Almost immediately after the 2012 election, the FTC abandoned its plan to file indictments and came to a voluntary agreement with Google instead. Only three years later, thanks to an accidental disclosure of unredacted materials in a bundle of FOI requests to a newspaper, did we discover the extent of the case against Google.

During Obama’s second term, many former Silicon Valley executives – including over 50 from Google alone – were appointed to key posts in the White House and in federal agencies. And so Silicon Valley had the people it wanted in key positions in agencies dealing with competition, privacy, intellectual property and telecoms regulation.

The second Obama term was crucial to the rise of the five tech giants, as it also coincided with a major shift in the underlying technology. These kinds of shifts have historically tripped up dominant players in the market. For example, Microsoft was unable to fully leverage its dominance on business and consumer PCs to the internet era. The second Obama term was when mobile 4G and low-cost smartphones became ubiquitous. For a period, analysts doubted if Google and Facebook could transfer their market positions to mobile. Even the two companies themselves argued that mobile was a perilous prospect. Of course, free from competition scrutiny, they pulled it off.

It was during this period that Facebook acquired WhatsApp and Instagram, and Google created its Android monopoly. The leading mobile apps are now almost all owned by Google and Facebook. And while Trump often talked tough against Big Tech, as did his federal-competition appointees, there was little effective action against any of the big players during his term. The US finally filed an antitrust lawsuit against Google a month before the 2020 election.

Of course, we shouldn’t just assume that greater enforcement of antitrust laws and competition policy would have automatically stimulated greater competition. Proponents of antitrust laws argue that the mere threat of scrutiny can create more competition and can stimulate innovation and new capital. There is plenty of evidence, for instance, that the decade-long lawsuit against IBM – from 1969 to 1982 – accelerated the creation of new markets, as IBM unbundled some of its technologies before the lawsuit ended. Some argue, albeit less convincingly, that Microsoft was so consumed by antitrust action at the turn of the new century that it failed to capitalise on the rise of search advertising and social networking.

But in other parts of the world, antitrust policy sometimes seems like a job-creation scheme for lawyers, particularly in the European Union. The European Commission can certainly launch initial actions quickly, operating as judge and executioner. Eye-catching press releases are issued, proclaiming a large fine against a Big Tech giant. But then the death-row haggling starts, and it can last a decade. After many years, the result tends to be a much smaller fine. And when this fine is amortised over many years, it has little impact on a business. In recent weeks, European commissioner Margrethe Vestager has lost three of her key antitrust officials to law firms of the kind that are typically then engaged by the tech companies.

Silicon Valley’s best rhetorical defence is to point to fears about government intervention in the market. This is a valid concern given how the desire to regulate internet services goes hand in hand with a partisan effort to regulate speech. A case in point is the ‘Facebook whistleblower’, Frances Haugen, who testified to the US congress yesterday on the alleged harms of what we are all being exposed to on our newsfeeds. She recommended a new commission to regulate Facebook (perhaps one she might be a part of).

Yet it would be deeply ironic to defend the Big Tech firms on the grounds of open markets and competition. After all, the unique privilege of the internet giants comes from a government-mandated special favour: Section 230, a freedom from liability that was granted to every ‘internet computer service’ (ICS) in 1996. ‘In hindsight’, observes Silicon Valley critic Scott Cleland, who served in the first Bush administration, this essentially divided ‘the US economy into predetermined winners (ICS) and designated losers (non-ICS, ie, everybody else) – via the most unlevel-playing field the US government could possibly create’. Section 230 created a ‘top-down, tech-first tyranny’, he says.

In reality, the alternative to an active competition policy is the status quo, in which large corporations strive not to compete with each other and regulate themselves. That is not going to stimulate young entrepreneurs to create better technology companies.

Andrew Orlowski is founder of the research network Think of X and a columnist at the Telegraph.

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.