Censorship is class war by other means

Christopher Hilliard’s A Matter of Obscenity exposes the paternalism driving censorship of the arts.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

When Penguin Books was prosecuted for publishing its uncensored edition of DH Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1960, the prosecution lawyer, Mervyn Griffith-Jones, posed a rhetorical question: ‘Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?’

Griffith-Jones’s appeal to gentlemen as the guardians of moral probity was widely seen as an indication of just how out of touch and paternalistic the censors had become. The press seized on his remarks and lampooned the prosecution, which eventually lost the case. Penguin sold two million copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in the six weeks before Christmas 1960.

The Lady Chatterley trial is widely seen as a landmark moment in the history of censorship in Britain. Christopher Hilliard certainly treats it as such in his new book, A Matter of Obscenity: The Politics of Censorship in Modern England, which explores the wider battle over censorship in the arts after 1857 – the year of the first Obscene Publications Act.

As Hilliard explains, a major motivation behind the Lady Chatterley’s Lover prosecution was the fact that the book was sold in a cheap paperback edition. Small editions of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and books like it, were already available in hardback, but these were too expensive to reach large readerships.

Paperback editions meant that erotic literature could reach a mass readership. This was why the director of public prosecutions (DPP) viewed Lady Chatterley’s Lover as a book that could lower the morals of common people.

Griffith-Jones’s rhetoric further revealed the class dynamics underpinning the Lady Chatterley trial. The defence was aided by the press, which mocked Griffith-Jones. Together, liberal lawyers and the media undermined the moral and legal authority of the elite, while advancing literary free expression. They also, of course, opened up commercial opportunities for publishers.

Indeed, there is a clear sense in which the Lady Chatterley trial was above all a victory for the managerial middle class of senior newspaper editors, lawyers, publishers and authors. Here it is worth looking at the 1959 version of the Obscene Publications Act, under which Penguin was acquitted. The act allowed the defence of literary merit as a justification for publishing erotic material. ‘The Obscene Publications Act of 1959′, writes Hilliard, ‘was the result of years of lobbying by authors to carve out a protected space for literature’. Lobbying bodies included the Society of Authors and the National Council for Civil Liberties (now simply called Liberty).

The Obscene Publications Act did not protect imported works or pornography. It protected the publication of ‘literature of value’ in England and Wales. From one perspective (the Whig view of history), we could see this as authors striving for more creative freedom and seeking to remove the hypocrisy of a class-based system of censorship. From another perspective (the elite theory of power), we can see this as the liberal bourgeoisie seeking to undermine the rival power bases of the patrician class and the Church.

As Hilliard shows, the act had been a long time coming. Back in the 1920s, James Joyce’s Ulysses became a test case for censorship. Imported copies were regularly impounded and destroyed. In 1926 literary critic FR Leavis deliberately challenged the censors by ordering a copy through a local bookseller so he could prepare a lecture on it at Cambridge University. Sir Archibald Bodkin, the then DPP, wrote to the university and stated that the book was not a fit subject for a lecture, especially for ‘a mixed body of students’.

Around this time the Metropolitan Police decided not to prosecute any translations of classics, deeming them de facto exempt from the law. Prosecuting possession of Boccaccio’s The Decameron or Petronius’s Satyricon made the police look foolish and boorish.

Yet even Radclyffe Hall’s unexplicit The Well of Loneliness (1928) was caught up in a censorship dispute – simply because it touched on lesbianism, despite the author intending to explore the suffering of ‘sexual inverts’ rather than celebrate their supposed depravity. The Well of Loneliness had been sympathetically and soberly reviewed before a star columnist at the Daily Express denounced it, prompted by concern about the perceived spread of lesbianism in the postwar era of the New Woman. Bodkin, as the DPP, wanted to prosecute but HM Customs and Excise felt that the novel treated lesbianism ‘seriously and sincerely, with restraint in expression and with great literary skill and delicacy’. Nevertheless, the destruction order (on behalf of the DPP alone) was granted and the publisher’s appeal failed.

The Lady Chatterley’s Lover verdict did not end literary censorship. Marion Boyars and John Calder, the publishers of Hubert Selby’s Last Exit to Brooklyn, were prosecuted in 1967 after rather recklessly daring the DPP to take them on. They were found guilty of publishing obscene material – although the Court of Appeal later quashed the conviction.

In general, deliberate defiance of the law and assaults on propriety provoked harsher legal responses than sexual explicitness. In the eyes of officials, puerility was worse than pornography. That is why the underground, counter-cultural magazine, Oz, faced legal action in 1970 but Penthouse did not. Oz advocated promiscuous sex, insulted authority figures and endorsed drug-taking – acts almost designed to attract official opprobrium. The editor-publishers of Oz were, in the end, convicted of obscenity.

Hilliard also gives special focus to Mary Whitehouse’s campaigns for Christian decency. In 1977 Whitehouse brought a private prosecution of Gay News for publishing a homosexual erotic poem about the crucifixion of Christ. She did so, however, under blasphemy laws rather than the Obscene Publications Act. Gay News lost the case.

Whitehouse was involved in legal wrangles over film and television, too. Hilliard gives very telling descriptions of the debate over film censorship at the time. Greater London Council member Enid Wistrich proposed the abolition of the council’s film-viewing board – of which she was appointed chair in 1973 – and (indirectly) a reduction in censorship. ‘Labour Catholics, older members, and, she noticed, many of the East Enders, were in favour of censorship; the teachers supported abolition’, Hilliard writes. Conservatives supported her, mostly in private, while Labour leftists were undecided – feminists had hardened into a largely sex-negative position by this point and therefore opposed liberalisation. Ultimately, Wistrich’s proposal was defeated because too few Labour GLC members backed her.

Hilliard also summarises the state of artistic freedom today. The picture has been complicated by the advent of the internet and the international publication and distribution of offensive and pornographic material. ‘Home secretaries and others’, he writes, ‘still have little to gain politically, and plenty to lose, from tidying up the law of obscenity’.

He explains the evolution of obscenity laws with well-chosen examples and a minimum of legal jargon. Overall, A Matter of Obscenity is an informative, even-handed and lucid study of British censorship in the 20th century. It is highly recommended, wherever you draw your personal lines regarding the division between the acceptable and unacceptable.

Alexander Adams is a writer and artist. His latest book is Iconoclasm, Identity Politics and the Erasure of History (Societas, 2020). His website is here.

A Matter of Obscenity: The Politics of Censorship in Modern England, by Christopher Hilliard, is published by Princeton University Press. (Order this book here.)

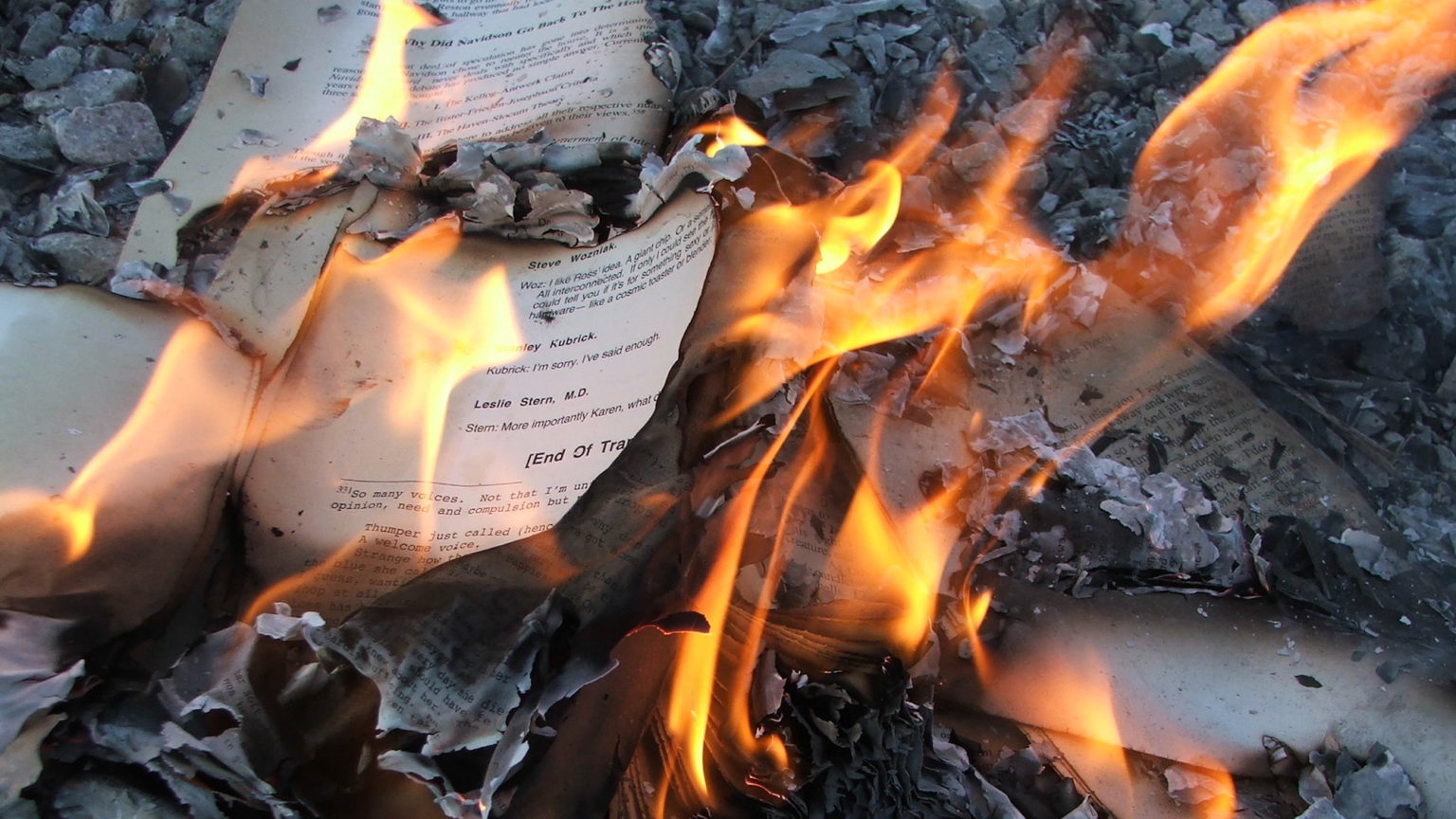

Picture by: LearningLark, published under a creative-commons licence.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.