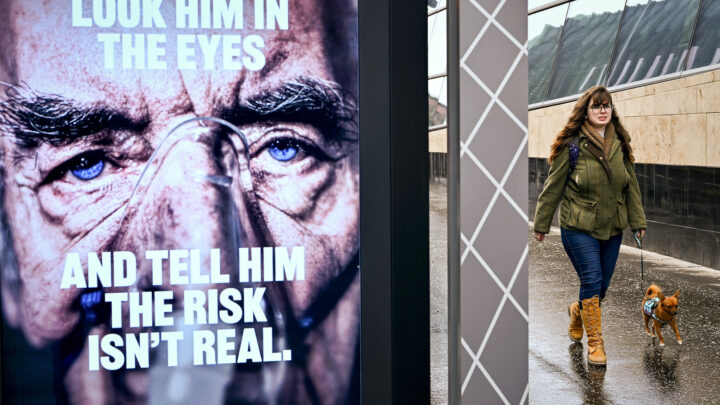

Are we overhyping the threat of Omicron?

Demands for harsher restrictions are far too premature.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Cancel your parties, work from home, keep your distance; another variant – Omicron – is in town. Questions about its transmissibility, severity and potential to escape vaccines have panicked policymakers. But what occurs next depends on how governments deal with uncertainties and how individuals interpret and respond to the perceived threat.

Decisions based on the vast array of Covid information are inherently uncertain. ‘There are known unknowns’, said Donald Rumsfeld, the former US secretary of defence. ‘That is to say, there are things that we now know we don’t know.’ And yes, there’s a lot we don’t know.

The Omicron known unknowns can be overcome with more evidence and data. Acquiring such evidence can help attain an accurate perception of the threat. But this takes time and effort, and it doesn’t make for exciting headlines. As a society, we are more accustomed to receiving snippets of information from a few sources. And, as a result, we have become impatient and lazy.

This evidence vacuum leads to disagreements, unchecked opinions, and the outsourcing of decisions to third parties about how we go about our daily lives. In consequence, as a society, we are becoming accustomed to being told what to do. Individuals can readily project their anxieties on to others – as many experts have done. In a state of ignorance and fear, the threat is distorted and bad decisions can follow. When evidence is de-emphasised and the role of experts is overemphasised, this fosters paternalistic and authoritarian policies.

Medicine itself has long dispensed with such paternalistic attitudes. Instead, clinicians seek to inform patients about what they may want or need to know. They share information, recognising a patient’s autonomy, values and his or her need to be informed about the risks and benefits of any given intervention.

Dealing with uncertainty is a vital part of medical training due to its importance for informing decisions. Clinicians who can’t tolerate uncertainty are more likely to over-test, over-interpret results and over-refer patients. Such intolerance further increases stress and burnout, and can lead to poor prescribing and have other detrimental effects on patients.

In the context of public policy more broadly, the presence of robust evidence makes the task of making decisions more straightforward. Conversely, its absence – as in the early stage of another variant – provides an evidence-free zone that makes the decision-making task more complex. The rapid development of certainty can prompt premature decision-making and increase the potential for error.

Answers to very complex questions become black and white. Uncertainty is suppressed as it instills a sense of dread about what’s next. What follows are political attempts to provide plausible protection from known unknowns. The threat has to be ramped up – and so, in this case, the increased transmissibility of Omicron is discussed as though it is incontrovertible.

The failure to reduce uncertainties is the single most abject failure of the response to the pandemic. Nearly two years in, we have still not researched the impact of those interventions that affect the whole of society – those interventions regularly rolled out when the threat is heightened, which lead to profound societal disruption and divisions.

However, there are several things that we do know. For instance, coronaviruses are seasonal in the northern hemisphere. As winter arrives, it therefore shouldn’t be that surprising that ‘about 1,000 daily respiratory admissions occur at this time of year in England’. We also know that virus evolution is relentless. An analysis of 12,754 US isolates of SARS-CoV-2 detected over 7,000 single mutations in the first few months of the pandemic. Some viruses such as influenza and coronaviruses mutate faster than others, such as measles. As viruses evolve, further variants will emerge – it’s in the job description of respiratory viruses.

Early evidence suggests illness with Omicron may be less severe. For example, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control reports: ‘All cases for which there is the available information on severity were either asymptomatic or mild.’ The WHO in Africa reports that ‘severe cases remain low in South Africa’. In addition, the South African Medical Research Council says that the much shorter average length of hospital stay of patients with Omicron is a significant early finding. Omicron may spread faster than other mutations or other respiratory viruses, but that does not necessarily make it a bigger threat. At present, in fact, other respiratory viruses the public has never heard of seem to have a considerably higher incidence than SARS-CoV-2.

The inability to cope with uncertainty may unnecessarily distress the population and cause considerable harm. Uncertainty and the quest for knowledge are the motors of science. Still, politicians and other experts who are intolerant of uncertainty will only seek to increase the sense of threat and instigate control measures based on little or no evidence.

In the face of uncertainty, the wise learn to watch and wait.

Carl Heneghan is a professor of evidence-based medicine at the University of Oxford and director of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.

Tom Jefferson is a senior associate tutor at the University of Oxford and a visiting Professor at Newcastle University.

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.