Years of hope and days of rage

Todd Gitlin on the Sixties, the New Left and the rise of identity politics.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Writer, sociologist and political radical Todd Gitlin died this weekend aged 79. To mark his passing we republish below a transcript of his reflections on the 1960s.

This, of course, was a decade Gitlin knew well. Not just through the anecdote and analysis of his marvellous The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage. But as a moment that he himself lived, and, in no small part, helped forge, from his time as the president of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), to his intellectual contributions to the New Left as a whole.

Gitlin was speaking to spiked in 2016 as part of a series of pieces on generational conflict. So here he is mainly focused on the generational form taken by the conflicts of that most momentous of decades. But he also touches on so much more, from the terroristic nihilism of the Weathermen to the rise of identity politics. His wisdom and insight will be missed.

On the 1960s generation

First of all, it’s probably true that most insurgencies take on a generational form (although it’s not the only form they take on). That’s because a political fight is about the undermining of a status quo, the desire to overcome it, to move on ideologically, culturally and so on. So upheavals tend to take on the perennial character of social conflicts, one rooted in the conflict between children and parents. This is not to say they’re reducible to parent-child conflicts, but there’s always a dimension of generational feeling at work.

So what of the limits of trying to fit the totality of the 1960s into a generational framework? Well, I think that in some ways the idea of the 1960s as a generational conflict was exaggerated. If we think about the anti-Vietnam War movement in the mid-1960s, it’s true it began largely as a movement of young people. Although very quickly, no sooner was there a movement of students and other young people against the war, than a faculty movement against the war crystallised in its wake, and worked alongside it. I’m thinking here of the teach-in movement in universities, the attempt to put academic intelligence to work on the problem of the Vietnam War, about which there was such enormous ignorance.

By 1969, one thing that is striking about the anti-war movement was how diverse it was. There was virtually no profession, no organisation that was without an anti-war strand. It was true of the clergy, and it was true of lawyers. It was true in cities, and it was true in small towns. The anti-war movement was everywhere. So while there was a generational element to the conflicts of the 1960s, there was also a cross-generational tendency.

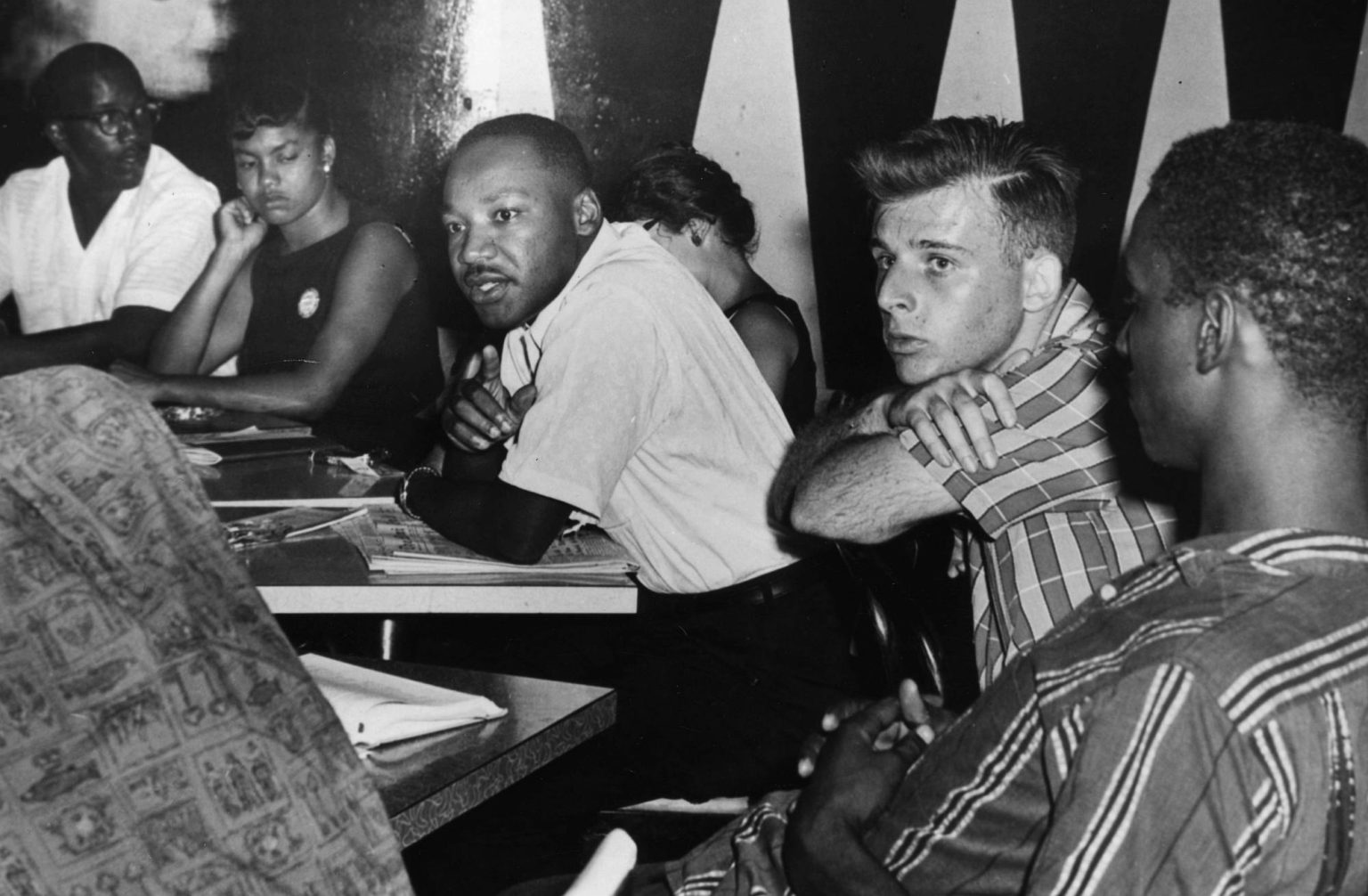

But if we go back to the civil-rights movement, which informed 1960s radicalism, the generational dimension is more evident. That is, the energy that goes into breaking with the past, that goes into trying out new tactics and strategies, the energy that was most palpable in the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955 and the emergence of Martin Luther King – that energy was largely the energy of an age-based stratum. Young Baptist ministers were in revolt against the failures and political limits of their parents’ generation. By 1960, a student component of the civil-rights movement had emerged and decided to become autonomous – the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, or ‘snick’, as it was known). By that time, King and his crowd were in their early thirties, and the SNCC was organised primarily by people in their twenties. So even there, within the civil-rights movement, there was a generational dimension.

So why did the social and political revolts of the 1960s often take on a generational form? Aside from the likelihood, as I’ve mentioned, that all insurgencies have a generational dimension, I think it had a great deal to do with the new place of young people in American society.

This was partly the demographic fact of the Baby Boom. Although most of the leadership of the student movement came from people who were a little bit older, who were born during the Second World War, and were therefore technically predecessors of the Baby Boomers, it is true that there was this huge population bulge – 1946 was the first year in which over four million babies were born in the US. And what’s conventionally known as the Baby Boom consists in the years in which that four million figure was surpassed – so that takes you from 1946 until 1964.

One thing that resulted from the Baby Boom was the enormous growth in higher education – the number of degrees granted by US universities doubled between 1956 and 1967. Rather quickly, then, you have an unprecedentedly large population of young people, who were often the first in their families to head off to universities, to social institutions that sheltered and protected them from the forces of adult life, providing what the great psychoanalyst Erik Erikson called a psychosocial moratorium, a crucible, a holding area in which social forms, bonds and close connections could develop. They were not pre-ordained to take a political form, but given what was going on in the world, many of these bonds did.

In addition to the expansion of universities, there was the increasing prominence of youth culture. Now, youth culture didn’t begin in the 1960s, but it was considerably amplified and, in a sense, radicalised by the emergence of rock music and eventually the movement of drug culture, from being a preserve of people of colour to the preserve also of largely white, student populations.

So I think the Baby Boom, the expansion of universities, and the intensification and radicalisation of youth culture were key contributors to the generational form taken by the insurgencies of the 1960s.

‘We are people of this generation’

It is striking just how self-consciously youthful the political insurgencies of the 1960s were. If you look at the sentiments of the left of the 1930s, for example, you won’t find anything like such a stark generational self-definition.

To explain this, I think you have to explore how cultural forms of definition develop. Reflecting on my own experiences, as well as how things played out for others, I do think the strong sense of generational divergence during the 1960s was created by the historical sequence: the Great Depression, followed by the Second World War and, then, the Bomb. There was a sharpness to the historical boundaries: depression, war, bomb.

I felt this acutely in relation to my own parents when I was trying to convince them that there was a generational gap, and that they were incapable of understanding it because of their age. I was acutely aware that my situation had a shape and a colouration that was different from theirs. I had never experienced the depression, and therefore I had less to be grateful about now that it was over. I had not experienced the war. I was born during it, but I had no memory of it. So I couldn’t take as much pleasure as they could from the fact that fascism had been defeated, and that they could enjoy a level of integration in American society that had hitherto been impossible. The fact that I was Jewish is also relevant. My parents grew up in an America in which there was a fair amount of systematic anti-Semitism. It wasn’t violent. But it was exclusive. So the fact I never experienced anything like that also intensified the generational divergence.

And for many of us on the New Left, or what was to become the New Left, a fear of nuclear weapons was baked into our understanding of what the world was in a way that it wasn’t for our parents. I was born in 1943. I had no memory of a world without nuclear weapons. From my point of view, when I argued with my parents, they couldn’t understand how radical was this break in human history.

The affluent society and its discontents

Among the incipient New Left, there was also a turn against the ‘American celebration’ and the so-called affluent society of the 1950s. As I wrote in The Sixties, there was a dialectic involving affluence and terror, a moral terror. That is, if you were of a rebellious spirit in a white middle-class world, your well of metaphors, your master narrative, was about a confrontation between a moral sense and absolute evil. The struggle against fascism was somehow personal, and transhistorical. To be alive to the world is to be alive to living on a moral razor’s edge. That’s why the work of Albert Camus, which reckoned with living ethically in an absurd, Godless world, was so important to us.

So the experience was not only of affluence, but also of a world that had gone through something horrendous, and something definitive, in which one was called upon to become who one really was, whatever form that took. The challenge was immense, and yet official society, the society of President Eisenhower, the mainstream of American culture, was just bopping along in denial, in concealment, in self-protection.

Now, what I’m describing is the core sensibility of the new activists, not larger youth culture. We were a much smaller, much more concentrated population – at this point in the early 1960s, we numbered about a few thousand people. And you can see this sensibility in the early passages of the Port Huron Statement, the 1962 political manifesto of the SDS. We had this sense of being historically anxious, of being unmoored, displaced, baffled and set apart because of a historical circumstance that we were trying to clarify to ourselves. So the world was instantly divided between those who took seriously the idea that there was a new human circumstance, and those who refused to acknowledge it. So you can see how the conflict, the cultural collision, would take a generational form.

New Left versus old left, and liberals

At this point, most of the old left was still trying to dig itself out of the Stalinist catastrophe. The events of 1956, when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev denounced the crimes of the Stalinist era in his ‘secret speech’, and the Soviet Union crushed the Hungarian uprising, smashed the self-confidence of the old left to pieces. A lot of people evacuated it. So it was easier for my crowd to take a step aside, to feel liberated from the old-left tradition, and the need to be liberated from that tradition.

The Port Huron Statement explains very well the reasons why we found liberalism unsatisfying. It wasn’t that it was wholly corrupted, as the old-left Leninist tradition was. It was that it was seen as too little – too little to overcome racism, racial segregation, too little to complete the welfare state, which was something that we wanted to do. And, as I wrote in The Sixties, we felt that there was enough anarchist and countercultural moodiness in the proto-movement for us to feel that the managerial side of liberalism was unsatisfactory. We were not only in revolt against reactionary capitalism, but also against big bureaucracy, centralisation, hierarchy. Those elements were not fully realised at the beginning, but they were there.

So we were part of a cultural change, and, in this sense, we were more closely aligned with elements of the anarchist tradition, which was, of course, never fully developed in America. I think it was part of a large historical move against centralised organisation, a historic shift away from the ideals of centralised command, including state socialism, as well as hierarchical forms of organisation. I think all of that was there; it was just very dimly seen at the time.

The generational cleavage grows

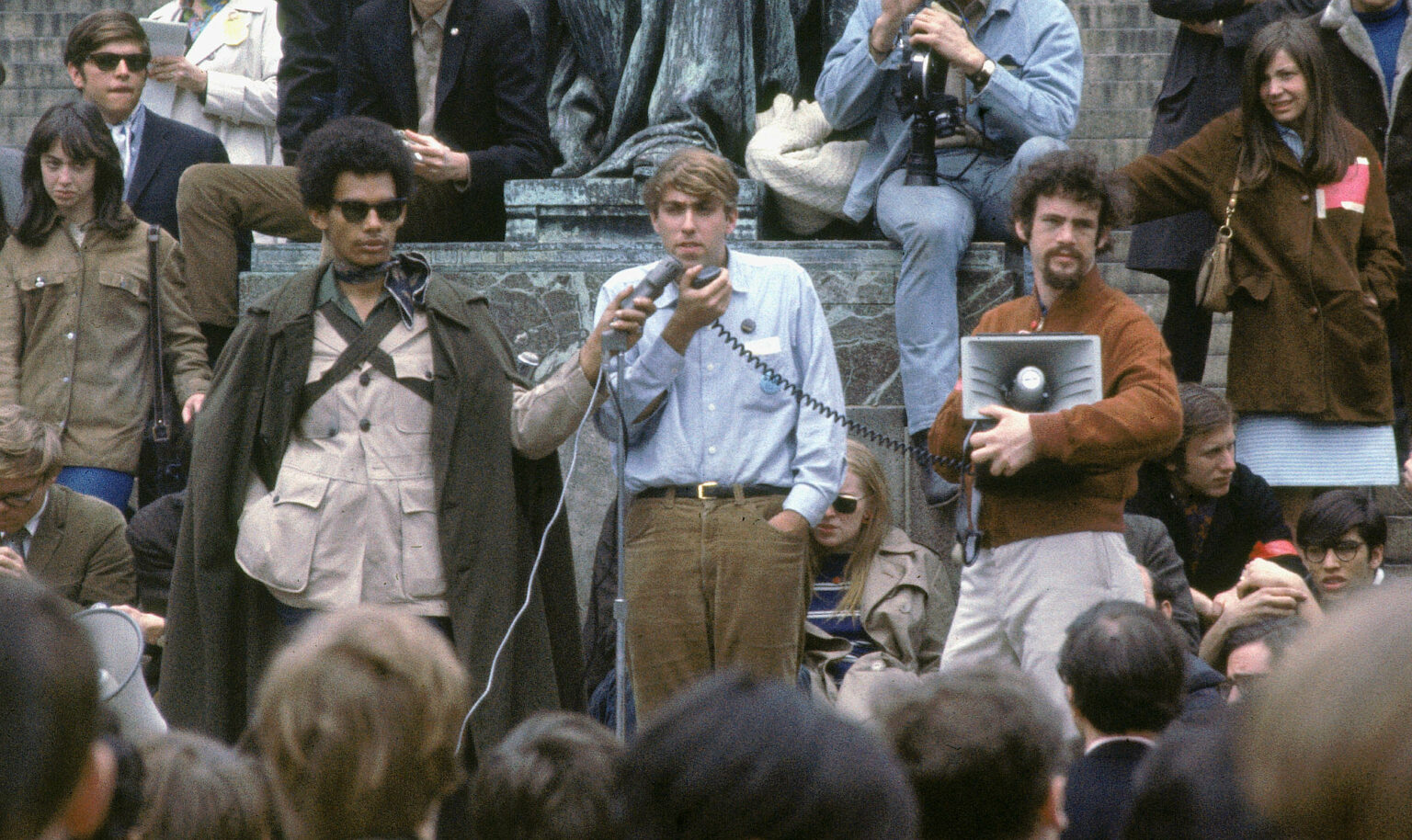

It was during the early 1960s that the generational idea first began to crystalise. And you can see that in the development of the self-conscious proclamations of student groups. You see it in SNCC in the South, you can see it in SDS, which itself was originally a branch of an adult organisation until it became clear there were generational cleavages, which weren’t just arguments about Communism, but about matters of style and culture – matters, that is, which were more important to us than to them. And, by 1964, you can see it in the emergence of the mass student uprising known as the Free Speech Movement.

Admittedly, the generational nature of FSM was partly exaggerated, thanks, in the main, to a journalist’s decision to present ‘we don’t trust anyone over 30’ as the FSM’s core sentiment. This was an almost wilful misunderstanding of what one of the FSM leaders had said when responding to a question about whether there were any Communists in the FSM. It was something like ‘Communists are old, and we’re new – we don’t trust anyone over 30’. But, even so, there was semi-truth inside the misunderstanding. That is, the revolt within the university was a revolt against old institutions and old assumptions about the ability and the right of the powerful to make fundamental decisions about what constituted acceptable university life.

That was at the end of 1964. From then on, the generational character of the movement becomes sharper, especially with the advent of the Vietnam War and the draft. The elements of generational consciousness are already in place, of course, but the drafting of young people for the war quickly exacerbated the sense of generational cleavage, of generational rupture.

The limits of generational consciousness

I started thinking about what I called the built-in dilemma of the radical student movement – the conflict between a ‘politics for others’ and ‘politics for selves’ – towards the end of the 1960s when I was trying to figure out what was going wrong. At that point I was trying to figure out why the New Left was overreaching, why there was a delusion about the class and generational identity of the movement, about what the movement, by itself, could accomplish. It became apparent to me, during 1968, which was when the movement’s militancy grew, that the movement had an inflated idea of its own power in America. And that delusion was leading to very serious political errors.

The SDS, in the early 1960s, was also wrestling with the problem of who the movement was for, and who would accomplish its aims, although it would have been formulated differently. The SDS would have said something like, ‘we are self-consciously radical. What are the agencies of change?’ This was the language C Wright Mills was using, and he was quite influential in those early years. So we saw ourselves, in a certain sense, as a vanguard, but we were mindful that we ourselves were demographically and socially limited. So then the question became, ‘where do you look for agencies of change?’.

But we didn’t really appreciate the class, cultural and other divisions that would complicate this model. So, in 1966, one faction of SDS started trying to theorise the idea of student syndicalism, the idea, that is, that students were the vanguard of a new class formation. So, in other words, people of a Marxist disposition were trying to enfold the cultural and class developments of the 1960s into a Marxist framework. It was part of the recognition that something odd was taking place, that student movements were different to previous radical social movements. It was argued that they were an anticipatory movement pointing towards a new class structure.

But students were fundamentally different from workers. Universities might be metaphorically similar to factories. But they aren’t factories. They are a stage of life.

Enter the Weathermen

The Weathermen, a grouping which emerged out of the SDS in 1969, tried to finesse the for-others, for-selves dilemma, with a warped view of the world. From the Weathermen’s perspective, the world was in the midst of a revolution led by people of colour, from the Cubans to the Chinese – in other words, we were in an indiscriminate Marxist-Leninist world. And, in America, which they saw as the imperial centre, the Black Panther Party was the representative of this global force. So the question for these white revolutionaries was how did they understand their role in the revolution. And the answer they cooked up for themselves was that they would be the catalysts, the organisers, the mobilisers, for a white working-class movement. And, by virtue of being violent and tough, they would be a vital component of the worldwide revolution.

It was pure fantasy, of course. The point about a world uprising was a third-hand approximation of a truth about what was happening in the Third World. But it was of no relevance to the US. So in order to make the model work, or seem to work very superficially if you weren’t thinking straight – and they were not thinking straight – was to assign to themselves the mission of representing a new lumpenproletariat wing of the movement, a wing that would still respect the leadership of people of colour.

The idea that there was this revolutionary force was completely delusional. And they discovered that when, in the summer of 1969, they summoned to Chicago these white working-class young people, who they thought existed on the side of the revolution. They expected that tens of thousands of people would show up. But, in the end, only a few hundred turned out, and they all got clobbered by the police. That was in October, and, within a couple of months, they decided that they could not finesse the dilemma, so decided to go underground and become terrorists of the deed. Over the next few years, they tried to accentuate the generational quality of what they were doing by emphasising the counterculture, by deciding that the counterculture was not reactionary, that it was the sea in which they could swim, to use their Maoist terminology. But none of that worked. It was phantasmagorical.

The rise of identity politics

In my book, The Twilight of Common Dreams, which is about the rise of identity politics and multiculturalism, I argued that the Marxist tradition had a universalist promise, but it was broken on the back of Stalinism. And the SDS, some of whose organisers came from the old left, were dimly aware of this, and tried to formulate a different version of universalism, predicated on the idea of participatory democracy. Essentially, it was an attempt to refound universalism on the idea that everyone is a citizen, and a participating citizen.

That was a noble attempt to resurrect the universalist promise of the left, but it failed. It failed to be luminous enough, compelling enough, livable enough to vivify an entire social movement. It turned out that people in the movement were more excited by thinking of themselves as part of a tribe or a sector, rather than as part of the universal. Thus people felt more acutely that they were black, or female, or, eventually, homosexual or some kind of ethnicity. They felt those identities more acutely than they did citizenship. So the push behind identity politics was pushing on a weak universal, a decayed, superseded universal, a universal that was no longer capable of generating a movement for itself. If you felt the power and the hunger for community, then you felt it as a member of a tribe, not as a member of an across-the-board universalist movement.

The Vietnam War served for several years as a universalising component. In other words, you may not know who you are, but you know you hate the Vietnam War. That was fairly successful as a unifying element, until, that is, the war was over, and America had lost. So then who were you? And there was no good answer to that question. Philosophically there might have been good answers. But, in terms of where people live, what people felt, there was no operative answer. So identity politics triumphed, partly because of the inspiration of the black liberation movement. But also because there was no really compelling alternative to it.

Boomer-blaming

Generational politics is easy. It’s convenient. I was talking before of how the depression, the Second World War and the Bomb were the pivots for generational definition. And there have been other more recent experiences that seem to divide history. There’s the end of the Cold War, the shakiness of the world economy and its financialisation, and, most recently, the economic crisis of 2008. Thus so-called Millennials have an experience of instability, of precariousness that is of a different order to that which my generation or even the next one after experienced. So there are world-historical phenomena that actually produce a very strong sense of rupture. And that’s in the real world, which is to say, at a certain point, family income did begin to decline, working income did start to fall, expectations of economic prosperity melted away – there is a material foundation for a sense of generational breakdown. So the resentment towards the Baby Boomers is born partly of resentment on the part of the dispossessed, or those fearful of being dispossessed, towards those who ‘made it’.

But, having said that, to see the huge historical, social and economic problems we face as generational ones, is a farcical exaggeration – a primitivisation, if you will, of the big changes taking place. But the oversimplification, the foisting of blame on to a generation, is noticeable. It has also been a long time coming. In the 1980s, oversimplification took the form of sneering at yuppies. There weren’t even that many yuppies. I once did a seat-of-the-pants calculation, and worked out that there must be at most 4.5million people in America who qualified as yuppies. It was not a vast population. But it was easy to turn on them as self-indulgent, culture-destroying sell-outs and so on.

I don’t want to underestimate the challenges of the young before this world of instability – the challenges are very great. But it’s a trap to think that you’ve been made to suffer by your prosperous, smug, pompous parents.

Todd Gitlin was a sociologist, novelist and cultural commentator.

Pictures by: Getty

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.