The grand folly of lockdown is coming home to roost

Britain is now paying an extraordinary price for shutting down society.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Usually, when the NHS is described as being at ‘breaking point’, this is just an overwrought metaphor. A winter crisis comes and goes, and then the health service staggers on. But the post-lockdown NHS backlog is now so large that it is genuinely threatening the very principle on which the NHS was founded – of universal healthcare, free at the point of use. This week, leaked minutes revealed that high-ranking Scottish health officials have discussed creating a ‘two-tiered’ NHS, where some patients would have to pay for care. Yet the NHS crisis, as severe and as deadly as it threatens to be, is just one of many parallel crises currently afflicting Britain. And in all of these crises, the past few years of lockdown have played a starring role.

The bleak truth is that in post-lockdown Britain, access to healthcare is no longer a given. NHS waiting lists are at record levels. Over seven million patients were waiting to start hospital treatment at the end of September. Over 400,000 had been waiting for over a year. This is more than double the pre-pandemic level. According to YouGov and Eurostat data, one in six UK adults were unable to access a pressing medical examination or treatment over the past year – the highest proportion in Europe.

Over the past several years, the Covid pandemic has put extraordinary pressure on hospitals. But the NHS backlog cannot only be blamed on virus patients taking up extra beds. Our ‘lockdown first, ask questions later’ approach must take a significant portion of the blame, too. Not only did the government’s lockdown messaging discourage the public from seeking treatment – the NHS also cancelled and delayed people’s treatments, even when hospital capacity was not being stretched.

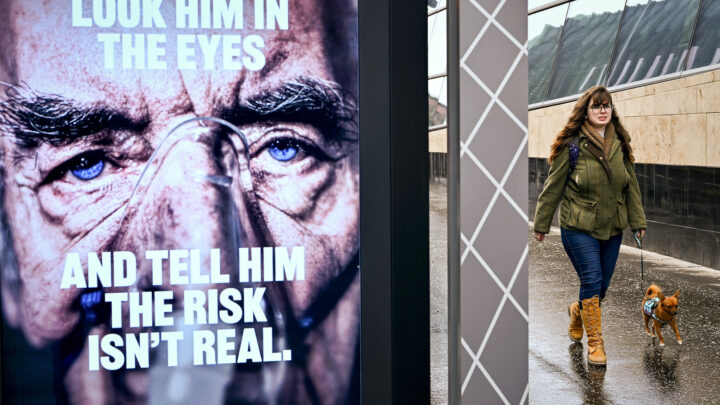

Although seeking healthcare was allowed under lockdown, there is no doubt that many who needed treatment, and who could have accessed it at the time, were reluctant or afraid to do so. After all, the public were ordered, in no uncertain terms, to ‘stay at home’. To stay at home or face arrest. To stay at home or get infected. To stay at home or kill granny. Back in October 2020, then health secretary Matt Hancock issued a stark warning to cancer sufferers: accessing treatment would be contingent on everyone obeying the rules. He said this when hospitals had plenty of spare capacity, with only around 3,000 Covid patients across all English hospitals at the time (at the peak of the second wave, more Covid patients would be admitted every single day). Even when there were lulls in the pandemic, the government’s priority was managing Covid. Other health issues came a distant second.

To see the folly of the UK’s approach, you just have to look at Sweden, which had no lockdown and far lighter restrictions. As a cancer surgeon pointed out in the Spectator last year, the difference in access to cancer services was astonishing. Taking prostate cancer as an example, during the first wave in 2020, the number of patients undergoing prostatectomies fell by 43 per cent in Britain, but by just three per cent in Sweden. Such a stark gap cannot simply be blamed on the virus. Lockdown is the difference here.

Perhaps the most obvious impact of lockdown has been on the economy, where a new grim milestone is surpassed every month. Shops, restaurants, offices and factories were shuttered for months on end in 2020 and 2021. Vast swathes of the economy were either mothballed or severely disrupted – far more by state-enforced restrictions than by the pandemic itself. The lockdowns of 2020 resulted in the UK’s worst recession in the history of industrial capitalism – a fall in economic output not seen since the Great Frost of 1709.

At the time, we were told that this didn’t matter. Rock-bottom interest rates and drunken money printing sustained the illusion that the economy was fine. ‘Building back better’ was not just a hollow slogan, it would be ‘the most likely outcome’ after lockdown, the experts assured us. Since lockdown ended, GDP has recovered somewhat, but we are now saddled with rampant inflation, with prices rising at their fastest rate in 40 years. Central banks are desperately trying to tame inflation by hiking interest rates and with ‘quantitative tightening’ – a 180-degree reversal on their pandemic policies. The bill for the printed money is finally here.

Soaring energy prices are a crucial driver of inflation, of course, but lockdown is not blameless here either. Energy markets were already in turmoil before the war in Ukraine provided the killer blow to global gas supplies. Back during the lockdown, demand for energy had been so low that for the first time in history, the price of oil plunged into negative territory, leading to sharp cuts in fossil-fuel production. The first energy shock came in 2021, as energy suppliers struggled to meet the energy demands of the newly reopened world. It was already clear by autumn last year, month’s before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, that an energy crisis was brewing.

These lockdown-induced inflationary pressures are not just eating into people’s pay packets. They are also compounding the other crises in our public sector. Months before chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s austerity budget last week, inflation was leading, inexorably, to real-terms cuts in defence and slower growth in spending on everything from health and social care to education and policing.

Arguably, the most needless crisis of them all is in education. There was never any justification for closing schools during the pandemic. Children were never at high risk from Covid. And yet, for months on end, they were denied an education. A select-committee report from March this year notes that when schools were closed British pupils ‘spent an average of only 2.5 hours each day doing schoolwork, and one fifth of pupils did no schoolwork at home, or less than one hour a day’. The universal education that had been enjoyed by children in England since the 19th century suddenly came to an abrupt end.

Schooling has now returned, of course, but many pupils have not. At the start of this year’s autumn term, nearly 100,000 pupils have simply vanished from the school system or fallen off the school register. Around 1,000 schools in disadvantaged areas have an entire class worth of missing children. This wanton destruction of the education system will be felt for years to come.

We might not have known exactly how lockdown would play out back in the spring of 2020. But it was obvious to anyone that upending every aspect of our lives would have serious consequences. Yet the governing classes dismissed the risks of lockdown. In fact, most of the elites wanted longer and harder lockdowns than the three we in England endured. They thought the most restrictive regime on economic and public life that had ever been devised was not restrictive enough. We should remember that today as we pore through the wreckage.

Fraser Myers is deputy editor at spiked and host of the spiked podcast. Follow him on Twitter: @FraserMyers

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.