The great Covid and fags cover-up

Study after study shows that smokers are less likely to get Covid. But this inconvenient truth has been buried.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

I achieved a personal milestone in April 2020 when, for the first time, one of my articles was flagged up as fake news on Facebook. spiked rather invited trouble by giving it the headline ‘Smoke fags, save lives’, but even with a subtler title it would have been enough to alarm Zuckerberg’s minions, since it discussed the growing evidence that smokers were heavily under-represented in Covid-19 wards.

Since back then Big Tech’s fact-checkers were still describing claims about SARS-CoV-2 being airborne and face masks preventing infection as ‘misleading’, a fake-news flag was something of a badge of honour. And, as with those claims, the ‘disputed’ information in my article has been borne out by the evidence.

After a brief burst of incredulous coverage in the spring of 2020, the media soon lost interest in the hypothesis that smokers are less likely to get Covid-19, but dozens of studies have been quietly published in the past two-and-a-half years which confirm it. I have been listing them on my blog and last week added the hundredth study. It seems a good time to stop. By any reasonable standard, the jury is in.

Of the 100 studies from around the world, 87 of them show a statistically significant reduction in SARS-CoV-2 infection risk among current smokers as compared to non-smokers. Seven of them found no statistically significant association either way. Two of them found mixed results. Four of them found a positive association between smoking and infection, although three of these looked at people with a genetic propensity to smoke rather than at smokers themselves.

The studies used a range of methodologies. Very few of them set out to look at the effect of smoking specifically, but epidemiologists tend to ask people if they smoke as a matter of course and so the association kept popping up. Some of the studies looked at specific outbreaks of Covid-19, such as on a French aircraft carrier. Several of them looked at healthcare workers, such as this one from Germany and this one from Chile. Others looked at groups of hospital patients, such as psychiatric patients in New York or HIV patients in South Africa. A large number of them used seroprevalence surveys to see who had antibodies and, therefore, who had been infected in the past (prior to the vaccines).

The findings are remarkably consistent, with smokers typically being 50 per cent less likely to catch the virus. Some of the researchers express surprise about this in the text of their study, others acknowledge that many other studies have found the same thing. Some of them discuss the possible biological mechanisms behind it, others do not mention the association at all. Some of them are clearly mortified to have reached a ‘pro-smoking’ conclusion.

Smoking cigarettes to ward off a respiratory disease does seem counterintuitive, I will grant you, and alternative explanations have been put forward. Some people have suggested that smokers spend more time outdoors, but this hardly seems likely to explain an effect of this magnitude. Besides, this study adjusted for ‘time spent outside’ and still found that smokers were 68 per cent less likely to get Covid-19. Some have wondered whether smoking might be under-reported by embarrassed smokers, but this wouldn’t explain it either, and several studies, such as this one, verified smoking status with blood tests. Others have argued, slightly desperately, that smokers are more likely to get tested because they cough more, but this wouldn’t explain the seroprevalence studies, nor the studies in which whole populations are tested at the same time.

Biological mechanisms exist to explain why smoking could protect from SARS-CoV-2 infection. I don’t pretend to be qualified to assess them, but the basic idea is that nicotine competes with the virus for the ACE2 receptor. The few studies looking at vaping have produced mixed results, but an intriguing study from the US found that Covid-19 patients who are smokers had better outcomes in hospital when given nicotine patches.

My list of studies is long, but I have probably missed some. I’m not claiming that it is a systematic review, although a meta-analysis of 57 studies published in Addiction came to the same conclusion: ‘Current compared with never smokers were at reduced risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.’ Incidentally, that meta-analysis also found that smokers were not at increased risk of hospitalisation and death if they got Covid-19, although former smokers were (presumably due to underlying health conditions).

One hundred studies, of which 87 per cent confirm the hypothesis, is a lot in epidemiology. If a similar body of evidence showed that smoking increased the risk of Covid-19 (or any other disease) it would have been considered settled science long ago. Instead, the evidence of a protective effect has been ignored, downplayed and denied. The issue only surfaced in the media twice after the spring of 2020. First, when a study was retracted because two of its authors had failed to disclose some rather tenuous links to the tobacco industry. And secondly, when a study was published in Thorax claiming that smokers were more likely to get Covid-19. This was one of the three studies that did not look at smokers, but rather looked at outcomes among people who had a ‘genetic liability for smoking’. The obvious problem with this method is that decades of anti-smoking education, regulation and taxation mean that lots of people who have a genetic liability for smoking do not actually smoke. Equally obvious is the fact that we should see higher rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection among smokers if this study were correct, but we don’t.

Those two news stories were enough to plant the idea in the public’s mind that the ‘smoker’s paradox’ was a myth generated by cigarette companies. Anyone who casually looks for information about it online will get the same impression. Google ‘smoking Covid-19’ and the top listing is an opinion piece in a medical journal by a paediatrician, who describes the association between smoking and reduced SARS-CoV-2 risk as ‘bizarre’ and ‘unhelpful’. The second listing is a webpage from the British Heart Foundation, titled ‘Does smoking increase or reduce your risk from coronavirus?’, which says ‘we don’t know for sure’ but strongly implies that it increases it. The third website is the Thorax study and the fourth website is a World Health Organisation webpage from June 2020, which claims there are ‘no peer-reviewed studies that have evaluated the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection among smokers’.

Google ‘tobacco Covid-19’ and the top listing is a WHO webpage that simply asserts: ‘Tobacco users have a higher risk of being infected with the virus through the mouth while smoking cigarettes or using other tobacco products.’ Below that is a journal article titled ‘Are smokers protected against SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19)? The origins of the myth.’ It claims that there is ‘no strong evidence that smokers are protected against SARS-CoV-2 infection’ and asks ‘how is it possible that such a potentially dangerous claim gained so much attention?’. The next listing is a hit job published in the British Medical Journal, which asserts that it has been ‘roundly disproved that smoking protects against Covid-19’ and strongly implies that any researcher who says otherwise is funded by the tobacco industry.

And so it goes on. Google any mixture of ‘smoking’, ‘smokers’, ’tobacco’, ‘cigarettes’, ‘Covid-19’, ‘Covid’ and ‘coronavirus’ and you will get a series of obfuscating opinion pieces and misinformation from the WHO. Add in words like ‘evidence’, ‘study’, ‘studies’ or ‘research’ and the Thorax study nearly always appears at number one. Even if you type in the title of my blog post (‘Smoking and Covid-19: a new evidence update’), the Thorax study comes up at number one.

I don’t know whether this is Big Tech rigging the system or the natural result of that study’s prominence in the media and medical journals, but there has been a concerted effort among people in public health to misrepresent the evidence. You could say that this doesn’t really matter. There are arguably no practical applications from the knowledge that smoking (or nicotine) reduces the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nobody was ever going to recommend smoking as a preventive health strategy and nearly everybody has had Covid-19 now anyway. But the truth needs no justification to be heard and if they can get away with lying about this, what else are they lying about?

Every epidemiological study worth its salt pays lip service to the truism that correlation does not equal causation, but, in practice, this is only raised as a serious objection when the findings are inconvenient. When it was noticed that obese people were over-represented in Covid wards, no one had any hesitation in adding obesity to the list of risk factors. At the start of the pandemic, Public Heath England asserted that ‘smokers with Covid-19 are 14 times more likely to develop severe disease’ based on a tiny study from China in which just five smokers were hospitalised with the coronavirus. They did not correct this ‘noble lie’ in the light of subsequent evidence.

Demanding an impossible standard of evidence for politically awkward findings, while inferring causation at the drop of a hat when the science supports the cause, has been standard practice in public health for decades. Based on observational epidemiology, public health groups, including the WHO, assert that ‘alcohol is a causal factor in more than 200 disease and injury conditions’, but when the same kind of studies overwhelmingly show that moderate drinkers live longer than teetotallers, the evidence suddenly becomes ‘inconclusive’ and ‘contested’.

It is the same when observational epidemiology shows that people who are overweight (as opposed to obese) live longer than people who have a ‘healthy weight’. Merely mentioning this fact was enough for one researcher to be hounded by public-health academics.

A bunch of studies show that smokers are less likely to suffer from dementia? Ooh, I think you’ll find it’s a bit more complicated than that, even though nicotine has been used to treat Alzheimer’s. But one study shows a link between passive smoking and dementia? Settled science!

The medical establishment’s approach to inconvenient facts was summed up by TV doctor Xand Van Tulleken, when he was asked about the smoker’s paradox on the BBC in May 2020. With the unbreakable confidence that only comes with having a medical degree, he said:

‘I haven’t looked into this particular bit of research, but I would discount it completely. It is definitely wrong.’

When evidence is dismissed sight unseen, we are in the realms of faith rather than science. Awkward facts become heresies, the heretics are condemned and the truth is withheld – all because the public are considered too stupid to handle nuance.

And yet the smoker’s paradox is more than an amusing curiosity. The relationship between nicotine and SARS-CoV-2 could offer promising avenues of research for dealing with coronaviruses in the future. We must hope that real scientists ignore their noisy cousins in public health and see where those avenues lead.

Christopher Snowdon is director of lifestyle economics at the Institute of Economic Affairs. He is also the co-host of Last Orders, spiked’s nanny-state podcast.

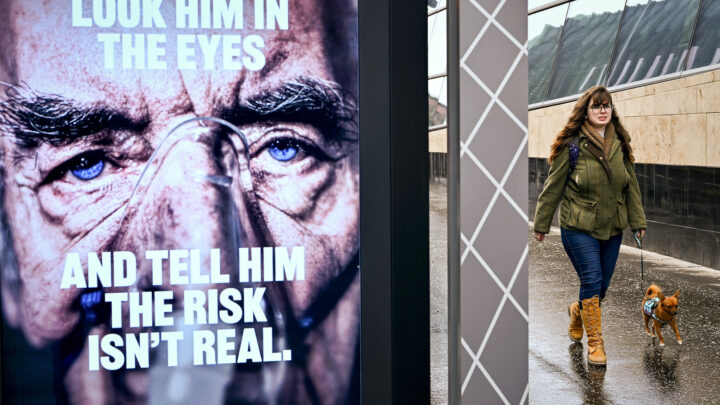

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.