The lethal cost of lockdowns

Britain’s high excess deaths show us why shutting down society was a fatal mistake.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

After a pandemic that predominantly killed the elderly and vulnerable, one might expect fewer deaths than normal in the years after it. But that doesn’t seem to be the case in the UK. Quite the reverse.

Deaths are currently more numerous than in pre-pandemic years. In 2022, the UK recorded more than 650,000 deaths, around nine per cent more than in 2019. In the week ending 13 January 2023, 17,381 people died, compared with a five-year pre-pandemic average of 14,544 for the same week.

A similar pattern can be seen across Europe. In Australia and the US, excess deaths for 2022 are also about 15 per cent above the pre-pandemic average.

There is no shortage of speculative explanations for the rise in excess deaths. According to the Guardian’s Owen Jones, the UK’s excess deaths are due to wicked Tory cuts in the NHS. This fails to explain comparable excess deaths in other countries. What is more, the number of NHS doctors and nurses has increased by 14 per cent and 11 per cent respectively since 2019. The NHS budget is up from £156 billion (inflation adjusted) in 2019-20 to £180 billion in 2022-23. So it isn’t as straightforward as Jones suggests.

Extreme anti-vaxxers are pushing an equally simplistic view. They effectively claim that excess deaths equal vaccine deaths. If that were true, then why does Sweden, which has a high Covid vaccination rate, have so little excess mortality? And why haven’t there been big death spikes in the heavily vaccinated 15-44 demographic? Vaccines have provided useful protection for those most at risk. They broke the link between infections and deaths in 2021. Even with the Omicron wave in 2022, the over-80s of South Korea and Singapore – extensively vaccinated with mRNA products – recorded proportionately fewer deaths than the over-80s of Hong Kong, who were often unvaccinated or vaccinated with inferior Chinese products.

The bulk of the evidence points to lockdowns as the main cause of excess mortality. After all, lockdowns disrupted healthcare in myriad ways from which it has yet to recover. During the pandemic, the National Health Service was transformed into the National Covid Service. Routine activity was cancelled. Patients avoided seeking out healthcare, despite their symptoms. Either they feared catching Covid in hospital, they didn’t want to be a nuisance or they were frightened to leave the house thanks to the orders to ‘stay at home’.

The GP system has also been upended by lockdowns. During the pandemic, it became difficult to secure a GP appointment and, at many practices, it remains so. Face-to-face appointments now comprise less than 70 per cent of all appointments, compared with 80 per cent before the pandemic. At the worst practices, less than 20 per cent of appointments are now in person. The risk of missed and delayed diagnoses ought to be self-evident. You cannot feel a suspicious lump or detect an irregular heartbeat over the phone, or if the patient gives up and doesn’t bother booking an appointment at all.

As early as December 2020, it was estimated that 4.4million UK cancer screenings had been missed. In the US, diagnosis rates of six common cancers fell between 16 and 42 per cent during the early days of the pandemic. The delays don’t end after diagnosis. In the UK, the proportion of cancer patients having to wait over two months for treatment is still growing. These delays impact prognosis and outcomes.

Cardiac deaths are a major slice of the current excess-death figures. Given that every minute counts when tending to heart-attack victims, the ever-rising delays in emergency care since spring 2022 are likely proving fatal.

Every medical specialist suspects more deaths are occuring in their field than the official data are recording. For instance, cases of blood poisoning (bacteraemia), due to the bacterium Escherichia coli, are ostensibly down by around 10 per cent per year since 2019. But there’s no reason why numbers should have fallen during lockdown. The obvious suspicion is that cases are continuing or are even rising, but they are passing undetected and untreated – hidden among the growing tally of people dying at home.

Furthermore, lockdowns promoted unhealthy lifestyles. Many of us sat about, eating too much and drinking too much while being stressed by apocalyptic news. In 2021, Public Health England reported that the average Briton gained half a stone during lockdown. Alcohol-related deaths hit a high in 2021.

Staying inside and apart from others likely weakened people’s natural immunity to other viruses. Normal life exposes us to mild infections, which then reboost our immunity. The ‘immune debt’ that resulted from disrupting this process best explains the recent spikes in Strep A infection, RSV and influenza – which are also now contributing to excess mortality.

Despite the vast cost of lockdowns, in truth they achieved very little. The initial Covid wave was already reaching its peak when the UK entered its first lockdown in March 2020. Sweden, then on a similar trajectory, opted for milder restrictions. For most of 2020 and 2021, the Swedes were berated as reckless and condemned for having higher mortality rates than their Nordic neighbours. Two years later, the UK’s Office for National Statistics found that Sweden, along with Norway, had the lowest total excess mortality in Europe from the start of 2020 to mid-2022.

Ever since mid-2021, Sweden’s excess mortality has tracked lower than in its neighbours, frequently dipping to zero. Also of note is that Sweden, with a large infection wave in 2020 and no excess deaths now, refutes the idea that excess deaths are the late-arriving consequence of Covid infections. If they were, Sweden would now be enduring more deaths than its Nordic neighbours, which experienced smaller waves of infection in 2020 and 2021.

In July 2020, Sweden’s chief epidemiologist, Anders Tegnell, asked to be judged in a year, not on the pandemic’s first few weeks. It has taken longer, but Tegnell has now been vindicated. Meanwhile, our own leaders abandoned long-prepared pandemic plans and adopted untried lockdowns, believing the fantasy that they would save lives. They will not be remembered so well. Their legacy is writ large in economic ruin and excess deaths.

David Livermore is a retired professor of medical microbiology.

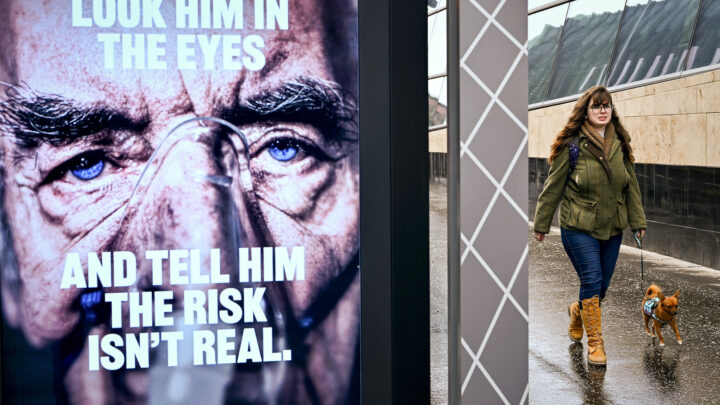

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.