How lockdown created a ‘cancer bomb’

Karol Sikora on the deadly consequences of ‘protecting the NHS’ during the pandemic.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

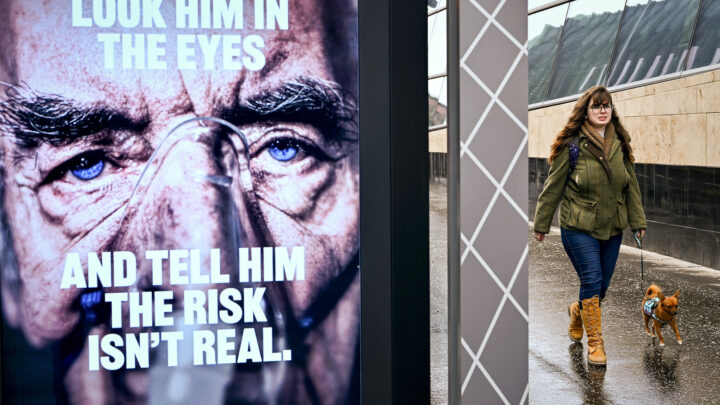

NHS waiting lists have reached record highs this year. In June, 7.6million people in England were waiting to start treatment. Almost 400,000 people have been waiting for over a year. Much of this backlog can be traced back to the lockdowns in 2020 and 2021, when patients suffering from anything other than Covid were warned to stay away from hospitals. This misguided attempt to ‘protect the NHS’ left illnesses undiagnosed and led to severe delays in treatment. Most serious of all has been the disruption to cancer care, which some experts now warn could be as deadly as the pandemic itself.

Karol Sikora – former chief of the World Health Organisation’s cancer programme – discusses Britain’s coming ‘cancer bomb’ in the latest episode of The Brendan O’Neill Show. What follows is an edited extract from Karol’s conversation with Brendan. Listen to the full episode here.

Brendan O’Neill: We hear a lot about the NHS backlog and the impending so-called cancer bomb. What’s your reading of the situation?

Karol Sikora: It’s really quite bad. We won’t see the true consequences on cancer survival for another two or three years. For context, roughly 1,000 people a day are told that they have cancer in the UK. That number doesn’t usually vary in the same way that more people get flu in winter. The numbers dropped, however, during lockdown – and the subsequent backlog has meant that those getting diagnosed now have more advanced stages of cancer.

The survival rates might not have changed much during the pandemic, but we’re likely to see those rates fall in the next few years. This will overwhelmingly be the case among those cancer patients diagnosed both during lockdown and beyond.

Survival rates change drastically depending on when the cancer is diagnosed. Take lung cancer, for example. If you catch it at stage one, the success rate with treatment is about 80 per cent. If it’s reached stage three or four, however, the survival rate drops to around 20 per cent. Delays in cancer diagnoses are invariably lethal.

O’Neill: What changed during lockdown?

Sikora: Everybody was fobbed off by the system. People with serious, persistent symptoms – such as coughing up blood – were practically unable to get a GP appointment. Online appointments were nowhere near as effective. And even when the GP referred you to a hospital, there were huge delays in getting scans or biopsies.

Some of these delays were understandable. But when the country began to recover from lockdown, we didn’t adapt fast enough. The almost religious attitude towards Covid ensured that everyone and everything else was forgotten about. Not just cancer, but also heart disease, strokes, psychiatric services and children’s health services. I’d love to know who made these catastrophic decisions and why they were implemented so irrationally nationwide.

The average age of people who died from Covid was 83. That’s the normal lifespan of a British adult. The average age of death from cancer is in the mid 60s. If you look at years lost rather than overall survival, deaths from cancer are going to be much greater because of what we did during the pandemic. Of course, it’s a tragedy when anybody dies. But if you have to save a 63-year-old or an 83-year-old, you choose the individual who has more of a life to live.

It’s easy to say this in retrospect, but this point was understandably lost in the rush to confront Covid. There should have been a balance.

O’Neill: You wrote last year that you get a lot of emails from people who are suffering because of the NHS backlog. What are they saying about their experiences?

Sikora: They’re very worried. While I would love to reassure everybody, there is no doubt that people have seriously suffered because of delays. And delay is a killer with cancer. How long before it has a significant effect is debatable, but even delays of just two or three months can be deadly.

The NHS was never good at diagnosing cancer quickly, even before the pandemic. We know that because the data from European countries of comparable wealth (France, Germany, Italy and so on) show that we’re much slower at catching cancer. When Covid hit those countries, the blip in diagnoses was rectified within six months. Cancer diagnostic services quickly returned.

No such normality has returned here. You only had to look at the vast, empty hospital car parks throughout lockdown to realise that doctors simply weren’t seeing people who needed help. It’s only a matter of years, if not months, before we see the irreversible consequences of the choices our leaders made.

Karol Sikora was talking to Brendan O’Neill on The Brendan O’Neill Show. Listen to the full conversation here:

Michael Shellenberger and Brendan O'Neill – live and in conversation

Tuesday 29 August – 7pm to 8pm BST

This is a free event, exclusively for spiked supporters.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.