The lockdown experiment must never be repeated

Scientists will one day have to reckon with their enormous mistakes.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The UK Health Security Agency – whose predecessor, Public Health England, employed me for a decade and a half – released a review last week, looking at the ‘effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions to reduce transmission of Covid-19 in the UK’.

Some commentators have written about this as if it is a definitive analysis of the efficacy of assorted lockdown measures. But that’s not the case. This ‘mapping review’ is just a trawl through UK studies that have investigated the impact of the non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) that were inflicted upon us between early 2020 and the start of 2022.

It does not appraise the quality of the material. The UKHSA’s fishing trip found some 151 studies, 31 of them by UKHSA authors. An astonishing two thirds – 100 – were based on modelling only. Just 22 were observational and only two involved trials to test specific interventions (and trivial interventions at that).

This is far from ideal working material, and the authors note that it ‘provides weak evidence in terms of study design, as it is mainly based on modelling studies, ecological studies, mixed-methods studies and qualitative studies’.

Occasionally, the review is oddly coy, especially on the effectiveness of ‘face coverings’, where it merely notes an ‘evidence gap’. This ignores the conclusions of January’s Cochrane Review – widely considered the gold standard of systematic reviews – on ‘Physical interventions for respiratory viruses’. Nevertheless, the Cochrane Review adjudged that there was no substantive reason to believe that masks are effective. Not even the N95 masks.

In short, the quality of the material identified by the UKHSA is poor. Nevertheless, while analysis is ongoing, the studies clearly don’t provide overwhelming evidence of NPI efficacy. Otherwise, you can be sure we’d have read about it, given the authorities’ and large parts of the media’s support for lockdowns.

There’s a deeper problem for the review, however, if the UKHSA’s intention is to develop a theory on how best to control SARS-CoV-2. Namely, Covid-19 was and is a changing virus. This means that the effectiveness of interventions alters over time, usually diminishing. Anyone doubting this should consider China, where stringent NPIs suppressed SARS-CoV-2 for much of 2020 and 2021, but failed spectacularly once the Omicron variant took hold in 2022. What worked against the early virus failed against its successors.

Furthermore, NPIs themselves likely accelerate a virus’s evolution. Evolution involves two distinct events. First, a random step to generate change. Second, a non-random step, in which the environment favours variants with useful changes. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, random errors occur frequently as the virus’s RNA genome is replicated by infected human cells. Most changes are deleterious, generating variants that swiftly die out. But a few changes increase the virus’s ability to infect new hosts. Variants with these changes then spread.

And here’s the critical point: by constraining the parent virus, a semi-effective NPI might therefore help new variants. For example, say a mask always filters out 90 per cent of virus particles, but with the new variant you need only inhale 1,000 virus particles to become infected whereas, with its predecessor, you need to inhale 15,000. The variant has then more than counterbalanced the effect of the mask. The mask will select for variants with this sort of increased infectiousness.

It’s helpful here to distinguish two sorts of NPIs: those that build a wall and those that create a bottleneck. An example of a ‘wall’ NPI is the use of condoms as protection against sexually transmitted infections (STIs). There’s nothing an STI pathogen can do to cross the wall, and condoms exert no selective pressure.

By contrast, the NPIs used against Covid created bottlenecks, not walls. Lockdowns meant that while you met fewer people, you still met some. Masks may have filtered some virus particles, but many passed through. Social distancing may have protected you from coughed droplets, but much less so from virus-laden aerosols. These NPIs exerted ‘selective pressure’ on the virus, encouraging variants that allow it to transmit more efficiently.

I believe that an example of this process was seen during the UK’s second lockdown, in November 2020. Total Covid cases in England drifted downwards from 20,000 per day at the start of the month to 12,000 at the end. However, cases in Medway and Swale (both in north Kent), grew remorselessly from early October to the end of December, despite the November lockdown.

Critically, Medway and Swale were the epicentre of the emergence and early spread of the Alpha strain, or the ‘Kent’ variant as it was originally called. Once lockdown was eased, this NPI-honed variant was ready to sweep Britain and then the world. Which it did during December and January.

The brutal conclusion is that, faced with a mutable virus, bottleneck NPIs will not only fail. They will also hone the virus. You might briefly force the R number (the average number of new victims infected by each case) to below one. But the pool of new victims remains, and a new, more spreadable variant will emerge by chance and find a way to reach them. Applying NPIs more strictly, as in China, just leads to a bigger final blowout.

The only uncertainty is how swiftly such NPIs will fail. But make no mistake, they will fail. And it is high time we realised this. The lockdown experiment must never be repeated.

David Livermore is a retired professor of medical microbiology.

Graham Linehan and Brendan O’Neill – live and in conversation

Tuesday 17 October – 7pm to 8pm BST

This is a free event, exclusively for spiked supporters.

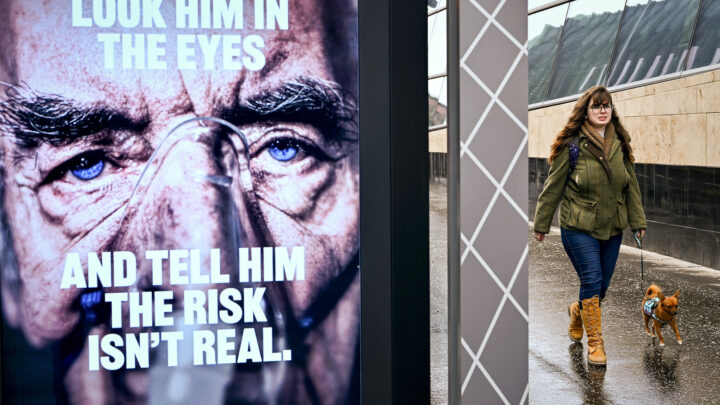

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.