We need to calm down about ‘Disease X’

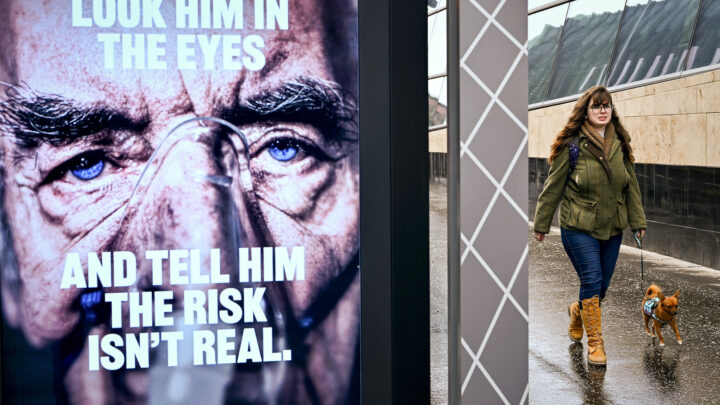

Public-health agencies are whipping up a panic over a virus that doesn’t exist.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

At the height of the 1720 South Sea Bubble, the world’s first financial crash, one wily promoter offered shares in an ‘undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is’. He promptly departed with the proceeds. Cryptocurrency pulled the same trick 300 years later, with ‘initial coin offerings’. Now, public health is in on the act, asking for funding and support to fight a non-existent pandemic. The name of the scam is ‘Disease X’.

Disease X doesn’t exist, but it was added to the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) catalogue of threats in 2018 as a ‘placeholder’. It received a huge boost in interest from the recent pandemic. We are told that it is 20 times more lethal than Covid-19, with the potential to kill 50million people worldwide. Supposedly, it comes from an animal source and the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) claims it is ready to develop a vaccine for it.

How worried should we be about this currently still fictional disease? The first point to grasp is that pandemics are rare occurrences in history. Antibiotics, sanitation and better nutrition make them rarer still in modern times. In my 45-year microbiology career, there have been two very serious pandemics – HIV and Covid – along with a few that looked momentarily concerning, such as swine flu and Zika. So, I don’t believe that Disease X is ‘already on its way’ despite being told so by ‘public-heath experts’. Even Wikipedia can only find 19 examples of plagues that killed more than one million people in the past two millenia.

The problem with the Disease X panic is that pandemics on that large a scale are generally a thing of the past. There used to be periodic bubonic plagues with between 10 per cent and 50 per cent population mortality, as with the Justinian Plague of the 540s, the Black Death of the 1340s and London’s Great Plague of the 1660s. Carried by rats, the bubonic plague spread to humans via fleas and then from human to human. There hasn’t been a major European outbreak since Marseilles in 1720, though China was hit late in the 19th century.

Nowadays, the likelihood of recurrence is nil. Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes the bubonic plague, can be cured with antibiotics. And even if some bad actor creates an antibiotic-resistant strain, there’s little scope for rapid spread given how rarely people are bitten by rat fleas nowadays.

Other bacteria have lost their chance to wreak havoc, too. There were cholera pandemics in the mid-19th century, spread via sewage-contaminated drinking water. In the Scottish village of Inver, the disease killed half the population. Thankfully, cholera was beaten by improved sanitation, including by Bazalgette’s London sewers. It isn’t coming back, either.

Next, there were fearsome pandemics when previously separated populations met and exchanged pathogens. The introduction of smallpox to Japan in 735 killed one-third of the population. When the Spanish conquistadors carried the same disease (and others) to the Incas and the Aztecs, this killed up to 90 per cent of the native population. In recompense, Columbus’s men returned to Spain with syphilis, which plagued Europe until the 20th century. Nowadays, though, no major population lives in isolation, smallpox is eradicated and syphilis is treatable. These kinds of pandemics cannot recur.

Respiratory-virus pandemics, however, do still occur. On average, there are a couple per century, with decent records going back to Tudor times. Most involve influenza, though the pandemic between 2019 and 2023, and very plausibly the so-called Russian flu pandemic between 1889 and 1894, involved coronaviruses.

None of these influenza pandemics, however, had a mortality rate of 20 times that of Covid-19, as we are told Disease X will have. Even the 1918-19 Spanish flu, which had far greater mortality than any previous or subsequent flu pandemic, killed only around 2.5 per cent of infected cases – not the five per cent we are told Disease X could be capable of. Besides, many of those deaths involved secondary bacterial pneumonia, which would now be treatable with antibiotics.

What if Disease X was something totally new, then, maybe from an animal? ‘Zoonotic’ transfers do occur and, we are told, may happen in the case of Disease X.

We can be certain that two recent coronaviruses did spread from animals to humans – SARS-1 from civet cats and MERS from camels. Both have mortality rates in the range of Disease X, but neither transmits efficiently and so not enough people were ever going to be infected for either to kill 50million people.

Some scientists believe that the Covid-19 virus came from an animal, too. But since the pandemic began in a city with a virology institute manipulating coronaviruses, it’s a whole lot simpler to think that SARS-CoV-2 is an unwisely engineered lab escape. In fact, it’s likely to have occurred precisely because researchers were undertaking ‘gain of function’ experiments to see how the next pandemic might evolve from a natural coronavirus.

Other nasties lurk in animals and occasionally spill into humans, notably the viral haemorrhagic fevers like Ebola, which likely originate from African fruit bats. However, transmission of these viruses is inefficient, requiring direct contact with the body fluids of an infected case. The biggest risk in the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone came from traditional ways of handling the dead. It is incredibly unlikely that one of these viruses could cause an uncontrollable outbreak in an advanced society. A nasty cluster, yes. But a pandemic, no.

In fact, HIV is the only good recent example of a major new pandemic that definitely came from an animal. It likely reached humans on multiple occasions, when west Africans prepared apes or monkeys as bushmeat dinners and cut themselves in the process, introducing simian viruses to the wound. Without treatment, HIV has a massive mortality rate, but transmission is via bodily fluids so it can be contained. It has killed 40million people, but it has taken 40 years to do so. Unless you’re desperately unlucky, it isn’t hard to avoid. I somehow don’t think this is the kind of scenario the modellers envisage with Disease X.

HIV does, though, lead us to the next important point – the unthinking optimism about vaccines. The UKHSA claims to already be working on a Disease X vaccine. But effective vaccines are hard enough to develop, even when we can identify what we’re vaccinating against. HIV vaccines have been sought for almost 40 years, with a singular lack of success, although other forms of treatment can keep the disease under control. It’s ridiculous to assume that you can design a vaccine before you even know what the disease is and how it behaves.

Of course public-health agencies should be thinking about possible future threats – including new pathogens, antibiotic-resistant variants of old pathogens and old pathogens becoming more widespread. That is their job. But ramping up fear over a fantasy disease, while pretending to combat it, is a sharp practice. It’s time we all calmed down about Disease X.

David Livermore is a retired professor of medical microbiology.

Graham Linehan and Brendan O’Neill – live and in conversation

Tuesday 17 October – 7pm to 8pm BST

This is a free event, exclusively for spiked supporters.

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.