How Covid killed parliamentary democracy

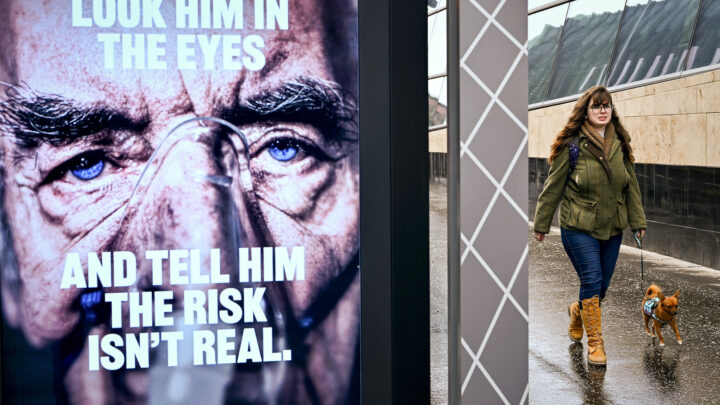

Draconian lockdown rules were imposed on us with minimal scrutiny from MPs.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The ongoing UK Covid inquiry is a calamity of missed opportunities. It has been almost entirely focussed on political tittle-tattle. Witness after witness has been invited to defend the scientific establishment, defame lockdown sceptics and lay all the blame for the failures of our Covid response on chaos inside No10. In doing so, it has determinedly ignored the elephant in the room. Namely, the failure of parliament during the pandemic to hold the government to account.

This failure is one of the themes of The Accountability Deficit, a new book that I have co-authored with colleagues at campaign group UsForThem. As Conservative MP Danny Kruger acknowledges in his courageous afterword to the The Accountability Deficit, parliament’s first duty should be to scrutinise, challenge and keep the government honest. If it abdicates that duty, the executive can fast become a chaotic gaggle of powerful but unaccountable individuals. The evidence shows that this is precisely what happened during the pandemic.

During the initial stages of the pandemic in March 2020, parliament was simply absent – at first metaphorically and then literally, as MPs were sent home. House of Commons speaker Lindsey Hoyle set the tone in early March, when he urged MPs to ‘think twice before tabling parliamentary questions’. Soon after that there were limits on the numbers of MPs allowed into the chamber and travel restrictions in place, which prevented many MPs from attending in person.

As the government imposed ever more draconian measures on the populace, parliamentary processes at times became farcical. A substantial portion of pandemic legislation was passed using mechanisms that avoided any debate in the Commons.

Even when parliament returned to the office during the summer of 2021, it was often denied the time or the information it needed to perform its role adequately. In one illustrative example in June 2021, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) failed to produce a mandatory impact assessment for parliament when the legislation requiring care-home staff to be vaccinated was presented for a vote. The deputy speaker called the situation ‘totally unsatisfactory’. This led one MP to later complain in the House of Commons: ‘How can we hold the government to account if they will not even answer our questions?’

Throughout 2020 and 2021, parliament and press provided minimal scrutiny of, let alone resistance to, the government’s draconian response to the pandemic. As then health secretary Matt Hancock’s leaked WhatsApp messages and now evidence from the Covid inquiry show, a small group of senior officials and ministers found themselves in an ever more powerful position. Without opposition, they became dangerously self-assured.

Ministers soon came to regard parliament as an inconvenience. In February 2021, Michael Gove refused to appear before the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, which was investigating the lockdown. The committee rightly described Gove’s refusal as ‘contemptuous’ of parliament.

Most serious of all, the initial lockdown order in March 2020 was made into law using an emergency legislative measure enacted the day after parliament had broken for Easter recess. Parliament didn’t debate lockdown until a full six weeks later. As Jonathan Sumption put it in October 2020, the government ‘deliberately delayed [its] urgent regulations so that there would be no opportunity to debate them before the recess’.

These seemingly cynical tactics were an indication of the disdain with which the government was prepared to treat parliament throughout the pandemic. Some MPs were clearly frustrated and angry. ‘We could perhaps have a painting next to me of Munch’s The Scream to get a sense of how I feel about the conduct of government business in this House’, railed Tory MP William Wragg during a debate on mandatory vaccinations for care workers in June 2021. ‘The government [is] treating this House with utter contempt’, he continued. ‘Ninety minutes on a statutory instrument to fundamentally change the balance of human rights in this country is nothing short of a disgrace.’

The UK government’s behaviour was indeed a disgrace. Yet the official Covid inquiry has not yet asked a single question about how parliament was cut out, bypassed, disregarded and disrespected. Neither the speaker nor the leader of the Commons, nor any non-ministerial MPs have been called to give evidence. At the very least, we should expect the inquiry to question Rishi Sunak on the government’s March 2020 amendments of parliament’s public-spending controls, which gave him freedom to spend more than £250 billion without parliamentary oversight – probably the biggest blank cheque ever given away by a parliament. And it should ask then prime minister Boris Johnson why his government chose to use the Public Health Act rather than the Civil Contingencies Act (which would have mandated much greater parliamentary involvement) to enact the March 2020 lockdown – the most draconian restriction on civil liberties and human rights known to this country in peacetime.

The government actively disregarded parliament during the greatest domestic crisis since the Second World War. The UK Covid inquiry risks compounding this betrayal of democratic accountability by ignoring it. We deserve better.

This piece was co-authored by Molly Kingsley, one of the founders of parents campaign group, UsforThem; Ben Kingsley, strategic legal affairs at UsForThem; and Arabella Skinner, the director of UsForThem.

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.