The fight for free speech in Ireland isn’t over yet

The government has shelved its proposed hate-speech laws, but this is not the end of its censorious agenda.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The Irish government’s mission to make Ireland the wokest place in the Western world suffered a setback late last week, when justice minister Helen McEntee quietly announced that the government was dropping its plan for highly controversial new hate-speech laws.

These proposed speech restrictions were included in the Criminal Justice (Incitement to Violence or Hatred and Hate Offences) Bill. McEntee has now conceded that ‘the incitement-to-hatred element [of the bill] does not have a consensus’. Describing these proposed hate-speech laws as lacking ‘consensus’ is a piece of masterful understatement. The legislation – which will live on with the hate-speech elements removed – has attracted criticism for its far-reaching implications for free speech, not just in Ireland but also across the West.

And with good reason. Dublin is home to the European HQs of various major tech and social-media companies, such as Meta, Google and X. If it had been introduced in its original form, the bill would have had a huge impact on social-media users across Europe and further afield, as those companies based in Ireland would have been regulated under the new laws. This would have given the domestic Irish legislation outsized global significance.

The original bill criminalised ‘incitement to hatred’, but its definition of hatred was completely circular. Ministers rejected all attempts to introduce a more workable and clear definition into the law, because doing so would make convictions ‘significantly more difficult to secure’.

The vague definitions didn’t stop there. The bill would have criminalised ‘hatred’ expressed against someone on the basis of their ‘gender identity’, which was defined as the ‘gender of a person or the gender which a person expresses as the person’s preferred gender or with which the person identifies and includes transgender and a gender other than those of male and female’.

Bizarre and confusing passages such as this were not drafting mistakes. They were a central feature of the proposed law, designed to create a state of uncertainty as to what would constitute illegal ‘hate speech’.

In a further chilling element, Section 10 of the bill would have made it an offence even to possess material that was likely to ‘incite hatred’. So even having offensive memes on your phone could have invited criminal prosecution under the proposed law.

It’s unclear how the government intends to proceed with the rest of the legislation. Still, we aren’t out of the woods yet where free speech is concerned. McEntee has said that the hate-speech element of the bill ‘will be dealt with at a later stage’, suggesting she may reintroduce these speech restrictions in a separate bill in the future.

Ireland has undergone a social revolution of sorts in the past 10 to 15 years. It has introduced gay marriage, abortion, gender-identity laws, as well as gender ideology into schools. The current Irish ruling class is made up of an overwhelmingly left-wing media, NGOs and academics, along with craven politicians eager to embrace wokeness as a way of – in their eyes – casting off Ireland’s Catholic and conservative past.

In tandem with this social revolution, Ireland has experienced major inward migration for the first time in centuries. Nearly a quarter of the Irish population is now composed of people who are foreign-born.

Recent high-profile crimes committed by migrants, combined with a complete failure of the government’s emergency-accommodation system for asylum seekers, has led to significant tensions and protests in communities across Ireland. The response of the government to these developments has not been to address the underlying concerns, but to propose a crackdown on free speech.

Ireland has become ground zero in the global censorship wars, due to the concentration of tech companies in Dublin. Indeed, Ireland’s media regulator will soon become the main enforcer for the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA). The DSA gives sweeping legal powers to the European Commission and national regulators to investigate and prosecute alleged misinformation, illegal content and other violations of the stringent rules imposed in the DSA.

So while the shelving of these hate-speech laws is to be welcomed, the Irish government’s efforts to control speech and thought are bound to continue. Those of us committed to free speech cannot afford to be complacent.

Lorcán Price is an Irish barrister and legal counsel for ADF International. He has been advising a coalition of Irish politicians opposed to the hate-speech bill.

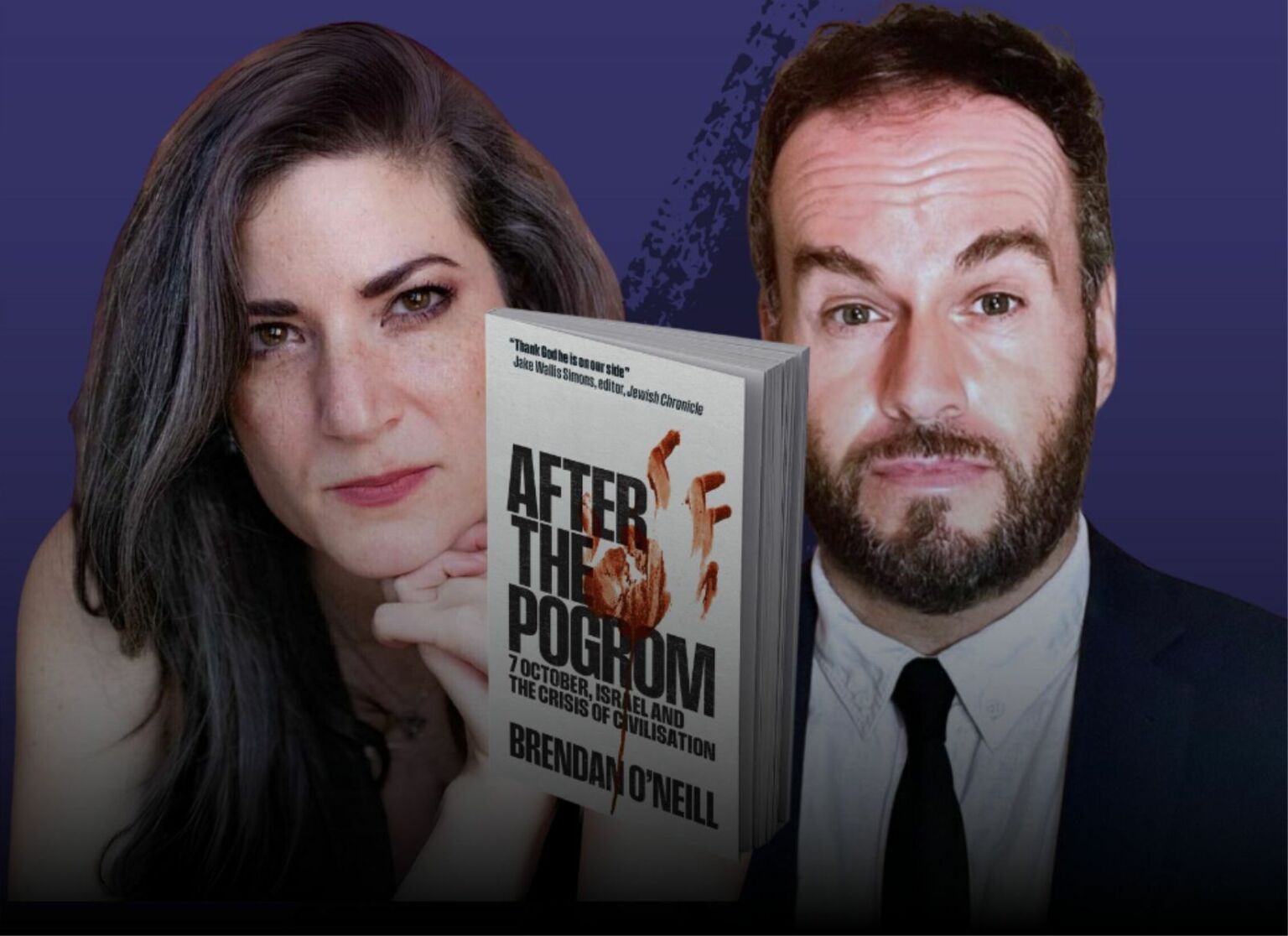

After the Pogrom – book launch

Tuesday 1 October – 7pm to 8pm BST

Batya Ungar-Sargon interviews Brendan O’Neill about his new book. Free for spiked supporters.

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.