It’s time to talk plainly about ‘assisted dying’

There is no ‘safe’ way to legalise life-ending medication.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

People often find it difficult to talk plainly about assisted suicide and euthanasia (ASE). ‘Assisted dying’, ‘physician-assisted death’ and even ‘euthanasia’ (from the Greek for ‘good death’) are all euphemisms to describe what is really intentional medical homicide, via the prescription of lethal drugs.

Last week in the Guardian, Labour MP Kim Leadbeater referred to the debate as one about ‘the rights and protections available to those in the last months of their lives’. Words like ‘safety’, ‘choice’ and ‘protection’ abound in the debate. Sarah Wootton, chief executive of Dignity in Dying, assures us that: ‘Safety is woven into the fabric of proposals for law change, introducing practical measures to assess eligibility, ensure rigorous medical oversight and robustly monitor every part of the process.’

The messiness, uncertainties, emotional charge and grisly details of the life-exterminating process are almost always carefully airbrushed. Leadbeater, who introduced a private members’ bill on ASE on Monday, has claimed that her proposed legislation will give us the right to ‘see out our days surrounded by those we love and care for, knowing that when we are gone they can remember us as we would like to be remembered’.

The mismatch between such language and the practical reality of what is being proposed should strike any right-thinking person as unsettling. As philosopher Kathleen Stock recently put it: ‘At times, it can sound as if one is being offered a particularly relaxing spa treatment. With a pleasing ring of supportiveness, you are now being “assisted” in achieving something, rather than being killed by a doctor or killing yourself.’

The details of what will be included in Leadbeater’s bill are currently hazy. However, the separate Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults Bill, introduced earlier this year in the House of Lords, could give us some clues (as a Lords private members’ bill, it is unlikely to succeed). It proposes that patients will be eligible to receive lethal medication if they have a terminal illness with less than six months to live, are able to make the decision to end their own life and have reached this decision ‘voluntarily, on an informed basis and without undue influence, coercion and duress’. What could possibly go wrong?

I worked as an NHS consultant for more than 20 years and am all too aware of many examples when my colleagues and I were hopelessly wrong in predicting how long a person had left to live. It is not uncommon for someone who is diagnosed with a ‘terminal’ illness to live on for years. This may be due to errors in diagnosis, unexpected spontaneous remission or the development of new treatments and medications. Prescribing lethal medication does, of course, make all of these options impossible.

For more than 15 years, I have also been a member of the council of a nationwide organisation that deals with the often tragic and expensive consequences of medical mistakes and negligence. I know that serious misdiagnoses are an unfortunate fact of life and are not uncommon, even in specialist centres. Legalising assisted dying would open up yet more opportunities for catastrophic medical mishaps.

The burden that would be placed on doctors would also be unreasonable and enormous. Two qualified doctors would not only have to certify a life expectancy of less than six months and ensure that there is no mental illness or impairment that might affect the patient’s judgement, but they would also have to assess whether or not there is ‘undue influence’ from others – ‘undue’ being a weasel word of extraordinary vagueness.

A hard-pressed doctor will be made responsible for identifying subtle emotional pressure, manipulation or ‘gaslighting’ from loved ones and relatives. Then she must choose the lethal medication, calculate the dosage and obtain the necessary medication. And then she would have to hand the medication over to the patient with the appropriate instructions and assistance to maximise the chances of a quick and uncomplicated death.

The possibilities for errors, accidents and abuse are obvious. Keir Starmer himself recently informed us that the NHS is broken, overstretched and failing. Is this really the best time for NHS doctors, pharmacists and administrators to take on this new responsibility?

Meanwhile, campaigners seem to live in an alternative reality, in which relatives would never pressure elderly and infirm people for their own gain. In the real world, this is sadly not the case. After all, elder abuse and coercive control by relatives is hardly unusual. It is inevitable that legalising ASE would open up new possibilities for serious and criminal abuse by relatives, particularly to prevent the dissipation of life savings on expensive nursing care.

Of course, most people don’t harbour malevolent thoughts towards their terminally ill loved ones. But the emotional distress an illness places on family members can itself be a major source of pressure. In the US state of Oregon, more than 40 per cent of those who end their lives through physician-assisted suicide said they felt they were a ‘burden on family, friends or caregivers’.

It would be naïve to assume this could never happen in the UK. Like most Western countries, the UK is witnessing a startling increase in the number of old and vulnerable people at a time when there is a progressive weakening and breakdown of traditional family support structures. The numbers of people living alone and those who describe themselves as lonely or socially isolated continue to rise year on year. Should ASE become legal, it could well become the easiest, or even only, option for many of society’s most vulnerable members.

That is not to say these people would actually want to die. The celebs and high-profile individuals like Ester Rantzen who have taken centre stage in the media debate about ASE are very much in the minority. Most people, as they face life-limiting diseases, are less concerned with asserting their ‘right to die’ and more concerned with trying to cope with the practical challenges they are facing. Yes, some would prefer to end their lives. But there are hundreds of thousands of suffering and sick people who simply wish to live.

John Wyatt is emeritus professor of neonatal paediatrics and medical ethics. His book, Right to Die? Euthanasia, Assisted Suicide and End-Of-Life Care, is published by IVP.

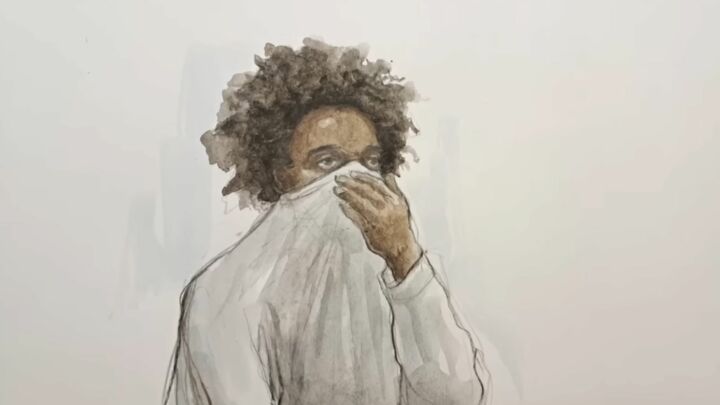

Picture from: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.