Long-read

Israel is not a ‘settler-colonial state’

The Jewish State was born through anti-imperial struggle.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Portraying Israel as a colonial imposition on indigenous people, a ‘settler state’ expropriating their land and culture, is a major pillar of Israelophobia. As I explain in Israelophobia: The Newest Version of the Oldest Hatred and What To Do About It, it is rooted in the suggestion that Jews have no place in the Middle East and are alien to the region, a claim that is easily dismissed with even the briefest look at history. Yet the demonisation persists.

Take Akub, a fashionable Palestinian restaurant in London’s Notting Hill. It is more than just a high-end eatery. In an interview with the New York Times in 2022, its French-trained chef and founder, Fadi Kattan, said his mission was to ‘reclaim a cuisine that is part of a broader Arab tradition involving foods like hummus, falafel, tabbouleh, fattoush and shawarma, that he felt was being co-opted by Israeli cooks’. It seems that whereas normal people cook food, in the eyes of Kattan, Israelis ‘co-opt’ it. This position relies on a highly selective view of history. As one reader remarked in the comments section: ‘Jews have also been making these foods for centuries and have appropriated nothing. There’s been a continuous Jewish presence in the land of Israel for thousands of years. What’s more, many of these foods are not limited to the land of Israel, but common across the former Ottoman Empire.’

People often forget that Judaism is two millennia older than Islam and 1,500 years older than Christianity. Israel was the cradle of Jewish civilisation. At least a thousand years before the birth of Jesus Christ, Jerusalem’s most famous Jew, King David, made the city the capital of the Land of Israel. It has been home to greater or lesser numbers of Jews – the very word ‘Jew’ is a shortening of Judea, the ancient kingdom radiating from Jerusalem in the Iron Age – in Jerusalem ever since.

Culturally, Jews have always intertwined their identity with the land of Israel, particularly since they were exiled to Babylon around 598 BC, when their powerful yearning for return took hold. For millennia, Jews in the diaspora have prayed facing towards the Holy City, exclaimed ‘next year in Jerusalem’ at Passover, mourned the destruction of the Temple by breaking a glass at weddings, longed to be buried there, prayed at the remaining walls of the destroyed Temple, and visited on pilgrimage. Many throughout history have taken the step of uprooting their families and returning to their homeland. All these practices continue to this day.

A thread can be traced backwards through Jewish history that shows the ancient roots of the ideal of repatriation. Beginning in 1516, Palestine – as it had been renamed by the Romans – fell under Ottoman rule, which would last for more than 400 years. Less than 50 years after the conquest, Joseph Nasi, the Duke of Naxos, a Portuguese Jewish diplomat favoured by the Ottomans, attempted to return Jews to their homeland without regard for scriptural prophecies about awaiting the coming of the messiah. In a way, he was the first Zionist.

The fortunes of the Jews of the Holy Land rose and fell over the following centuries. In 1860, the British financier Sir Moses Montefiore, who believed in the divine providence of the British Empire and the Jewish return to Zion, founded the community of Mishkenot Shana’anim just outside the Old City of Jerusalem. Composed of red-brick alms houses and a windmill, it was the earliest forerunner of the future state (the windmill still stands today).

Modern Jewish migration to Palestine began in 1883 with an influx of 25,000 Jewish arrivals, many fleeing anti-Semitic mobs in Russia and inspired by a desire to return to their ancestral lands. Jews also came from as far afield as Persia and Yemen, grouping into their own neighbourhoods. Immigrants from Bukhara, Uzbekistan, including the Moussaieff family of jewellers who had cut diamonds for Genghis Khan, created the Bukharan Quarter (Shkhunat HaBucharim), with its distinctly Central Asian feel. Their imperative to return had been building for thousands of years.

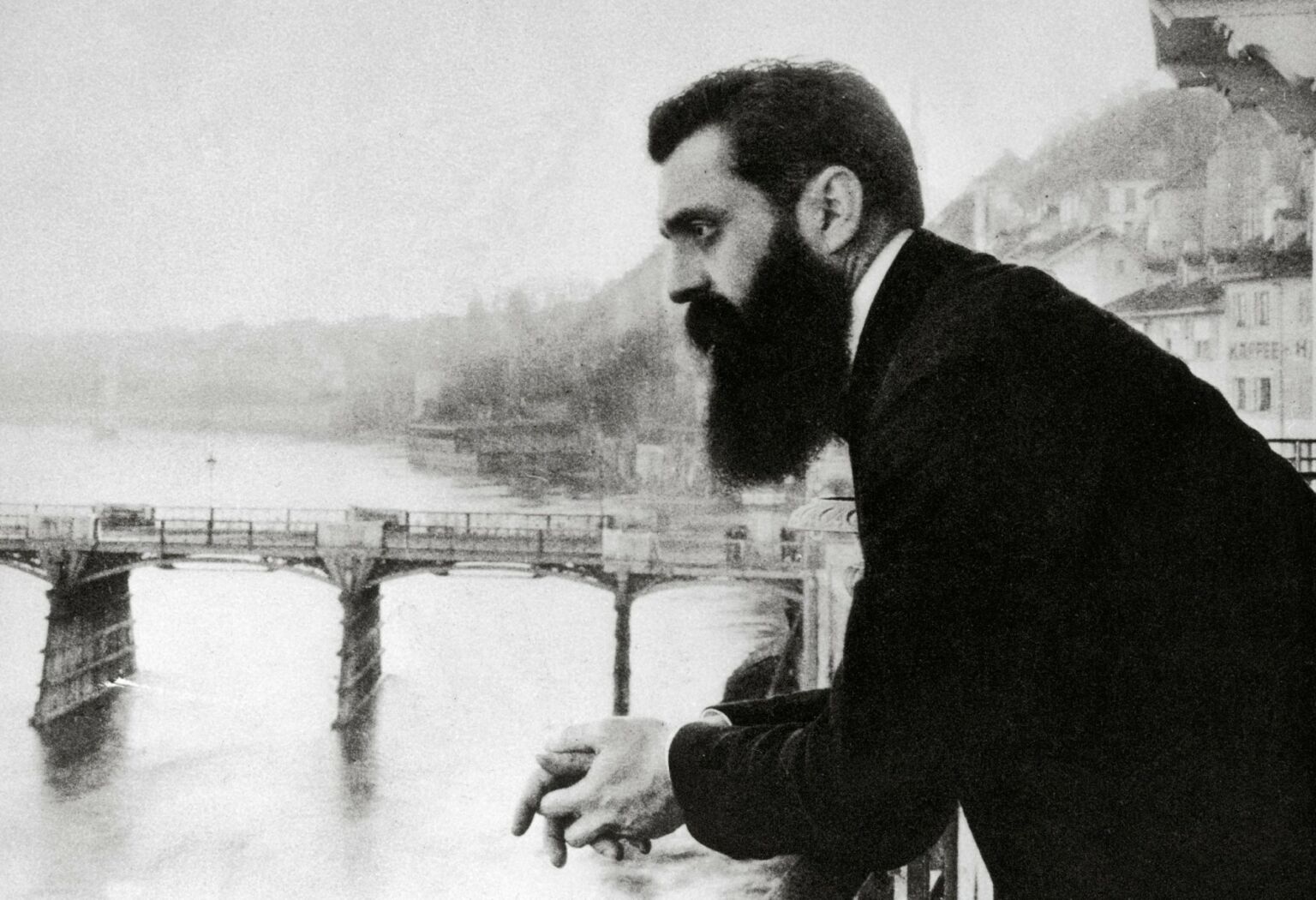

Writing in the Jewish Chronicle in 1896, Theodor Herzl, the father of modern Israel, laid out the concept of Zionism. ‘I am introducing no new idea’, he pointed out. ‘On the contrary, it is a very old one. It is a universal idea – and therein lies its power – old as the people, which never, even in the time of bitterest calamity, ceased to cherish it. This is the restoration of the Jewish State.’ He added: ‘It is remarkable that we Jews should have dreamt this kingly dream all through the long night of our history. Now day is dawning. We need only rub the sleep out of our eyes, stretch our limbs, and convert the dream into a reality.’

Eighteen months later, in 1897, came the famous first Zionist Congress in Basel. Afterwards, Herzl wrote in his diary: ‘L’état c’est moi. At Basel, I founded the Jewish state. If I said this out loud today, I would be greeted by universal laughter. Perhaps in five years and certainly in 50, everyone will know it.’ (1)

Four further waves of immigration followed, as Jews fled butchery around the world for Ottoman-controlled Palestine. By 1896, more than three-fifths of the 45,300 residents of Jerusalem were Jewish (2). Yousef al-Khalidi, the mayor of the city, wrote to his old friend, Zadok Khan, chief rabbi of France: ‘Who can contest the rights of the Jews to Palestine? God knows, historically it is indeed your country.’ In 1915, as the contours of the future Jewish state were continuing to emerge, Palestinian Arab nationalism had yet to appear. ‘Questions of Arabs and their nationality are as far from them as bimetallism from the life of Texas’, wrote TE Lawrence of Arabia at the time. ‘Christians and Mohammedans come [to Jerusalem] on pilgrimage; Jews look to it for the political future of their race.’ (3)

During the First World War, the Turks sided with the Germans. After their defeat, the Ottoman Empire collapsed and huge swathes of its territory passed into the hands of the allied powers. The Ottomans had administered their territories in vilayets, or cantons, and these became the basis for the carve-up by the allies. In the Middle East, French Syria took three vilayets – Damascus, Aleppo and Beirut – which were home to Maronite Christians, Shia and Sunni Muslims, and Druze and Alawites. The French later divided the territory into Syria and Lebanon. British Iraq was created out of three vilayets – Baghdad, Basra and Mosul – stitching together a patchwork of Shia and Sunni Muslims, Yazidis, Kurds and Iraqi Jews. After independence, the country proved as ungovernable for the Iraqis as it had been for the British. The vilayets of Palestine, inhabited by Sunni and Christian Arabs, Druze, Bedouin and Jews, were placed under a British mandate, meaning that Britain would administer the territory until the inhabitants were eligible for self-government, at which time independent nation states would be born.

Thus, in 1917, the British Empire became the first Christian power to rule Jerusalem for more than seven centuries. It was the fulfilment of a long-held aspiration. Prime minister David Lloyd George famously described Jerusalem as ‘a Christmas present for the British people’, having exclaimed, ‘Oh, we must grab that!’. On 11 December, after routing the German-led Ottoman forces in one of the last successful cavalry charges in modern warfare, Field Marshal Edmund Allenby dismounted and entered the Holy City on foot. Britain had just issued the historic Balfour Declaration, a statement of support for a ‘national home for the Jewish people’ in Palestine, intended to detach Russian Jews from Bolshevism. This was typical of the tactical pledges made by the Great Powers under wartime pressure, many of which contradicted each other. Governing the mandate was not easy, as Jewish aspirations for statehood grew and tensions with the Arabs mounted. In the 1930s, Palestinian nationalism was born, sparking cycles of internecine violence.

Then came the Second World War. The Holocaust deepened the case for a Jewish state, which would be able to stand its own army and fulfil the pledge of ‘never again’. In the manner of an indigenous people revolting against the British Empire – and sharing a common struggle with other colonised nations groaning under the imperial jackboot – Jewish guerrillas mounted an armed campaign against the British to push them out of Palestine. As had become the norm across the Middle East and Europe, in 1947, the UN agreed to partition the land into a Jewish state and a Palestinian one, with borders traced around ethnic-majority areas (the vilayets of Jordan had been parcelled up and placed under Hashemite rule a year before). Under the terms of this two-state solution, Israel would comprise 56 per cent of the land, while the Palestinians would occupy 43 per cent. The populations would be mixed, with half-a-million Arabs on the Israeli side, and 10,000 Jews living in the State of Palestine. Israel’s neighbours reacted with dismay; they had harboured their own lust to annex the territory. On 14 May 1948, eight hours before British rule officially ended, in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art on Rothschild Boulevard, David Ben-Gurion, the country’s first prime minister, got to his feet and proclaimed Israel’s independence. Forty-four years after Herzl’s death, his prediction had come true.

The Jewish side had accepted the UN partition plan. After all, to the north, the Syrians and Lebanese had likewise agreed to be partitioned, despite much grumbling from the Alawites and Druze. But the Palestinians – led by the Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini, who had collaborated closely with the Third Reich during the war and relished the idea of exterminating the Jews – rejected any treaty that involved the establishment of a Jewish state. Just hours after Ben-Gurion’s speech, following Husseini’s lead, the armies of Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon and Syria attacked the fledgling Jewish country. ‘This will be a war of extermination and a momentous massacre’, announced Abdul Rahman Hassan Azzam, secretary-general of the Arab League, ‘which will be spoken of like the Mongolian massacres and the Crusades’. The Mufti called for jihad, crying: ‘Murder the Jews! Murder them all!’ Ironically, as the scholar Joseph Spoerl has pointed out, ‘the plan for ethnic cleansing in Palestine in 1947-8 was an Arab plan, not a Zionist one’ (4).

An existential struggle ensued. Stalin, who had been the first to recognise Israel, ensured that it received invaluable Soviet armaments from Eastern Europe, and with its organised and determined fighting units – many of whom had survived the Holocaust – the Jewish State withstood the onslaught. In the chaotic Sturm und Drang of war, about 700,000 Arabs fled their homes. As historian Simon Sebag Montefiore recounts: ‘Some were expelled by force, some departed to avoid the war, hoping to return later – and approximately half remained safely in their homes to become Israeli Arabs, non-Jewish citizens in the Zionist democracy’ (5). The Palestinian refugee problem, writes historian Benny Morris, ‘arose as a product of the war, not of planning, on either the Jewish or the Arab side… It was partly the result of malicious actions by Jewish commanders and politicians, but to a lesser extent Arab commanders and politicians were responsible for its creation through their orders and failures.’ (6) The existence of two million Arab citizens of Israel today shows how allegations of ‘ethnic cleansing’ have long been twisted and weaponised.

After nine months of fighting, the war ended. The 1949 Armistice Agreement, supervised by the UN, split Jerusalem and placed the Old City in the hands of King Abdullah of Transjordan, who had also succeeded in annexing the West Bank, which the UN had set aside for the Palestinians. ‘Nobody will take over Jerusalem from me unless I’m killed’, he declared. The terms allowed Jews access to the Western Wall, the cemetery on the Mount of Olives and the tombs of Kidron Valley, but these pledges were never honoured. Jews were not able to visit the wall for the next 19 years, and their gravestones were defaced.

With an uneasy peace restored, there was a further ingathering of the exiles. Immigrants arrived from all over the world, including many of the 900,000 Jews who had been driven out of their homes in the great anti-Semitic purge of Arab lands. Today, nearly 80 years after the War of Independence, 80 per cent of Israeli Jews were born in Israel and half of the country’s Jewish population is now black or Middle Eastern, meaning that whites are in the minority. Far from being a white-supremacist state, Israel is a deeply multiracial one.

The demonisation of Israel presents it as a unique historical evil. In truth, the manner of its creation was typical of the period. These historical facts show that, unlike the United States, Australia or the South American countries, Israel was founded as a post-colonial state, not a colonial one, established legitimately under international law after the withdrawal of imperial Britain. Sadly, for the remainder of the 20th century and what we have seen of the 21st century, the Palestinian territories and Israel – along with Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Jordan – have been beset by typical post-colonial problems of ethnic rivalry, expulsion and unrest, and now war.

Indeed, aside from the singularity of the ancient Jewish story, the Holocaust and the volume of migration from the diaspora, only two things were exceptional about Israel’s birth. First, the 50 per cent of the Arab population that had remained within its borders were granted full citizenship. Second, despite its messiness, it became a liberal democracy with a strong economy, which made it unique in the region. Yet despite all this, Jews are still blamed for stealing the hummus.

Customers of the Akub restaurant are served their ‘reclaimed’ dishes against a backdrop of rows of keys displayed on the wall. These represent the property that was lost by the 700,000 Arabs who fled when Israel was founded, fuelling demands for restitution. Palestinian dispossession has become one of the world’s best-known historic injustices. In that same period, millions of other people were driven across borders in Europe and Asia, amid the same post-colonial turmoil, in more violent circumstances, their homes seized, their relatives killed, their cultures lost and their families fragmented. Yet their stories have been buried by history.

Who laments the plight of the Greek Orthodox Christians, or the Indian Hindus and Sikhs, or the Armenians, or the Irish refugees created after the bloody British partition of 1921, or the 12million ethnic Germans expelled from Eastern Europe on Churchill’s instigation after the Second World War? Or the Jews of the Middle East, for that matter?

That’s not to say that Israel’s sins must not be condemned, or that the Palestinian injustice should be forgotten. It’s simply a question of exposing demonisation. And no nation it seems is more singled out and demonised than Israel.

Jake Wallis Simons is a journalist, author and editor of the Jewish Chronicle.

The above is an edited extract from Jake’s most recent book, Israelophobia: The Newest Version of the Oldest Hatred and What To Do About It.

(1) Jerusalem: The biography, by Simon Sebag Montefiore, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2020, p451

(2) ‘The Jewish Presence in Jerusalem through the Ages’, by Manashe Harrel; and ‘The Arabs in Jerusalem’, by Ori Stendel, in Jerusalem, by Sinai and Oestericcher (eds), John Day, 1974

(3) TE Lawrence in War and Peace: An anthology of the military writings of Lawrence of Arabia, by TE Lawrence and Malcom Brown (ed), Greenhill Books, 2005, p106

(4) ‘Palestinians, Arabs and the Holocaust’, by Joseph S Spoerl, in Jewish Political Studies Review Vol 26, Numbers 1-2, March 2015, p25

(5) Jerusalem: The biography, by Simon Sebag Montefiore, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2020, p451

(6) ‘Vertreibung, Flucht und Schutzbedürfnis: Wie 1948 das Problem der palästinensischen Flüchtlinge entstand’, by Benny Morris in FAZ, 29 December 2001

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.