Long-read

Unlearning the lessons of Prohibition

A hundred years on, and some people still think curtailing citizens' everyday freedom is a good thing.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

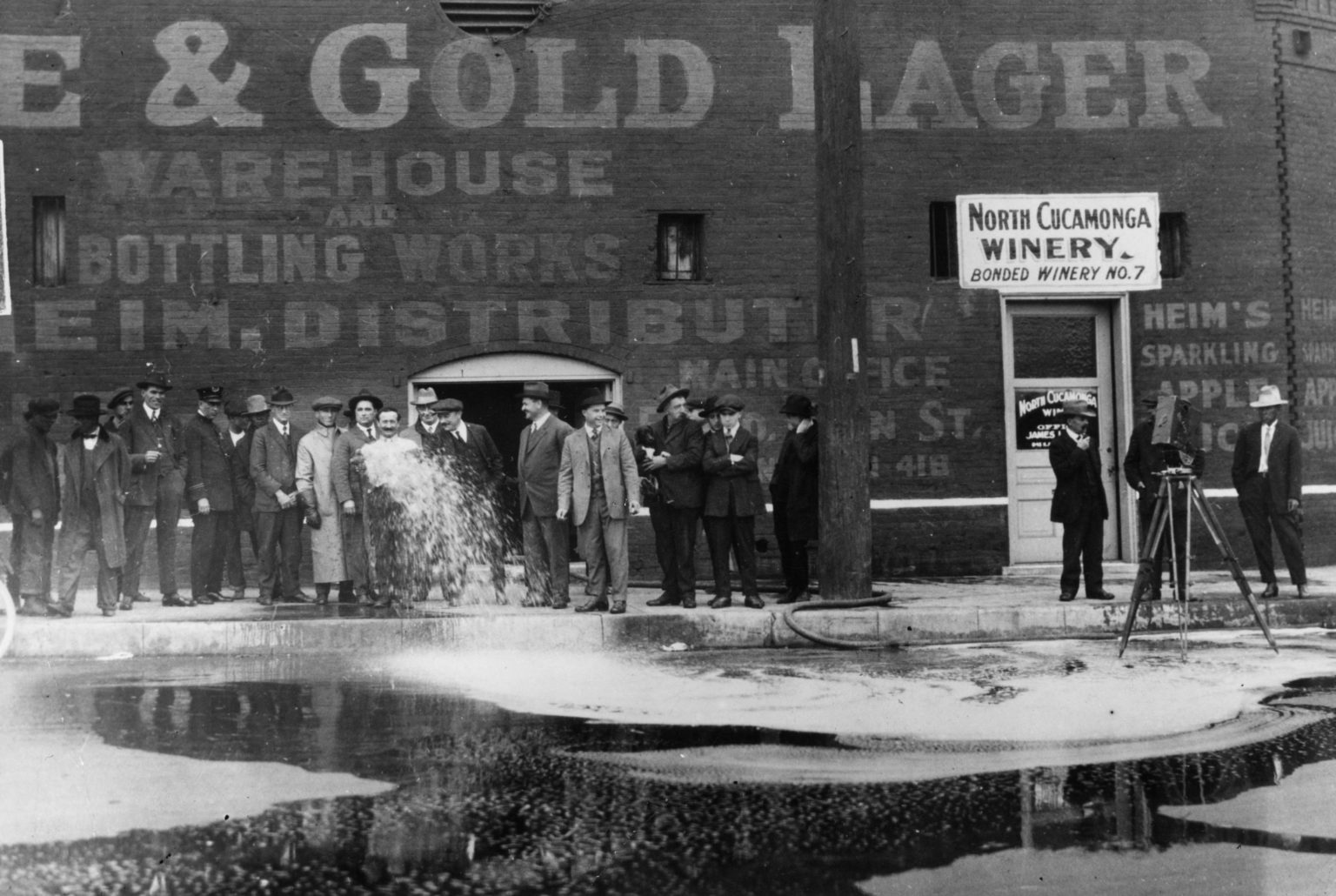

On 17 January 1920, the United States embarked on the ‘noble experiment’ of banning the sale, manufacture and transportation of alcohol. To mark the occasion, the rabble-rousing temperance preacher Billy Sunday held a mock funeral for the demon drink and predicted that ‘[t]he slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corn cribs. Men will walk upright now, women will smile, and the children will laugh. Hell will be forever for rent.’

As every schoolboy knows, things didn’t work out that way. The 18th Amendment banning alcohol is the only constitutional amendment that took away liberty, and it is the only one that was repealed. And yet prohibitionists in 1920 had good reason to believe that their country would be ‘bone dry forever’. Repealing the amendment required ratification by three-quarters of US states, a seemingly unthinkable majority. Furthermore, the 18th Amendment was soon followed by the 19th Amendment giving women the vote. Female activists had been at the forefront of the prohibitionist movement for decades in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and Anti-Saloon League. Since women were less likely to drink and were portrayed as the chief victims of the ‘liquor trust’, it was assumed that their votes would give prohibition an impregnable democratic shield.

In the event, the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform was formed in 1929, and became one of the most influential voices in favour of repeal. Four years later, prohibition was gone, its name synonymous with idiotic government overreach, doomed utopianism and Al Capone.

Was it all bad? Apologists for the temperance movement occasionally surface in the press, most recently in the Guardian, where the feminist argument for prohibition made a surprising reappearance. Revisionists point to several developments in the 1920s which were, from their perspective, positive. Per capita alcohol consumption fell during prohibition, they say, and remained below pre-prohibition levels until the 1970s. Rates of liver cirrhosis were low in the dry era, and did not substantially rise until the 1950s.

The ‘noble experiment’ seems to have had a lasting impact not only on how much Americans drank but also on how they drank. The biggest temperance organisation of its time was not called the Anti-Saloon League for nothing. Grubby, hard-drinking, male-dominated saloons disappeared in 1920 and never fully returned. The bars which opened after repeal owed more to the mixed-sex speakeasies of the dry era. By the end of the 20th century, two-thirds of alcohol was consumed in the home and at private parties.

The contrarian, galaxy-brain take is therefore that prohibition was actually a success. This argument was put forward by David Aaronovitch in The Times recently. But even if you ignore all the murders, poisonings and organised crime, it is hard to swallow. It is true that the US enjoyed a steep decline in liver cirrhosis mortality, but this mostly took place in the years before national prohibition began. Some of this may have been due to the state-wide prohibitions that preceded it, but Britain experienced a steeper decline in the same period and, like the US, saw historically low levels of drinking for several decades after the First World War. At a minimum, this suggests that similar outcomes could be achieved without resorting to such an extreme measure as prohibition. And while the old-fashioned saloon was an undoubted casualty of 1920s, it is a matter of opinion whether this was a good thing.

At the most fundamental level, it did not prohibit, nor did it create a society in which alcohol became taboo

In any case, you really can’t overlook all the murders, poisonings and organised crime. The homicide rate rose in the US throughout prohibition, peaking in the year of repeal, before falling sharply. This is unlikely to be a coincidence. Interestingly, the suicide rate followed a similar pattern and there is little evidence of a decline in drunkenness. The ban on alcohol not only gave birth to modern organised crime — it also revived the Ku Klux Klan, normalised police raids on private property, created the template for the FBI, and led to the creation of the heavy-handed American penal state, as Lisa McGirr shows in The War on Alcohol. It led to the US government adding poison to industrial alcohol and effectively murdering thousands of its own citizens. This was in addition to the tens of thousands who were blinded, crippled or killed by moonshine.

One can accept the likelihood that some people were prevented from drinking themselves to death under prohibition while acknowledging that the many health and social problems that were unleashed ultimately outweighed the paternalistic benefits. Prohibition certainly reduced alcohol consumption somewhat – it would have been extraordinary if it hadn’t. But it did not deliver what the prohibitionists promised. At the most fundamental level, it did not prohibit, nor did it create a society in which alcohol became taboo. The jails were not turned into storehouses; by the end of the 1920s, they were overcrowded with prisoners, half of whom had been convicted on charges related to alcohol.

After a decade of this turmoil, Americans concluded that prohibition had been a net failure. That is why the 18th Amendment, which had once seemed invincible, was repealed by the 21st Amendment on 5 December 1933. It took just nine months to get the requisite 36 states to ratify it, including Ohio, the home of the Anti-Saloon League and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.

The problem with arguing about whether prohibition ‘worked’ is that it implicitly acknowledges a false premise. It suggests that the policy would have been commendable had the government been able to enforce it properly. But as Daniel Okrent, author of the excellent Last Call, writes, the worst thing about prohibition was that ‘it took away an individual right’. All the problems we associate with prohibition stemmed from people responding to their right to drink being violated, but we should not imagine that prohibition would have been a ‘success’ if the public had meekly submitted.

In retrospect, it is obvious that there were far too many drinkers in 1920 for national prohibition to have ‘worked’ in the sense of being respected. But even if the US had avoided all the murders and poisonings, there would have been nothing noble about the experiment. It was a hideously illiberal policy with strong undertones of xenophobia and class prejudice, and would have been no less objectionable if drinkers had been an obscure minority. Prohibition was dreadful both in practice and in principle.

A recent study, which found some positive health effects from earlier statewide prohibitions, finished by saying: ‘Whether or not these benefits exceeded the costs of prohibition remains an open question.’ Why? Because ‘importantly, if individuals are utility maximising, value-of-life measures lose meaning since they do not incorporate the lost utility from forgone alcohol consumption’. The authors are economists, and it shows, but their point is that people enjoy drinking. Assuming they know the risks, drinkers take more out of alcohol than alcohol takes out of them (to paraphrase Churchill). If you deprive them of this pleasure, or make it pricier or more difficult to acquire, you are doing them real harm. This is a crucial aspect of public-health policy that is rarely mentioned in the public-health literature.

Prohibition was by no means a purely American phenomenon. It is often forgotten that the same law was in force in Iceland, Finland, Russia, Canada and Norway at around the same time. It didn’t ‘work’ in these countries either, and they had all abandoned it by the mid-1930s (although, incredibly, beer remained illegal in Iceland until 1989, and full prohibition was not repealed in the Faroe Islands until 1992).

Today, alcohol prohibition lives on in the Islamic world and in parts of India, where the kind of mass poisonings that were once common in the US continue to occur. Illegal hooch killed at least 100 people in Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh last February. Two weeks later, moonshine killed 150 people and hospitalised 200 more in northeast India. Prohibitionists might argue that you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs, but where is the omelette?

The simple lesson to learn from such ‘noble’ experiments is that if you try to prohibit activities, which are none of the government’s business and are regarded as perfectly acceptable by a significant section of society, you cause more damage than if you left them alone. Laws that protect people and their property command general respect. Laws that seek to stamp out private behaviour, the consequences of which can be avoided by those who do not share a taste for it, neither deserve nor receive respect (the word ‘scofflaw’ was coined during prohibition to describe the millions who refused to comply).

Regrettably, not everyone has learnt the lesson. Alcohol is under no imminent threat of prohibition in the Western world, but ad hoc bans continue to appeal to both the conservative right and the progressive left. The stigma of prohibition remains strong enough for modern-day prohibitionists to steer away from the word, but the objective remains the same. Some anti-tobacco extremists have borrowed the old prohibitionist trick of using the word ‘abolition’ to invoke the genuinely noble cause of ending slavery. Others employ the euphemism ‘endgame’ to describe the looming, inevitable ban on cigarettes. Last year, the British government set a target of going ‘smoke-free’ by 2030. ‘Smoke-free’ used to mean that smoking was banned indoors. It now means the total eradication of combustible tobacco. It is difficult to see how this could be attempted without draconian laws.

Beverly Hills is set to become the first place in America since the days of the Anti-Cigarette League to ban the sale of all tobacco products. The tiny kingdom of Bhutan banned tobacco sales in 2004, with predictable consequences. When the ban was passed, an editorial in the Lancet said: ‘That is what we call progress.’ The prevalence of tobacco-use has risen from nine per cent to 25 per cent since its prohibition began. A study published in 2011 found ‘a thriving black market and significant and increasing tobacco smuggling’. Who could have seen that coming?

If you deprive people of a pleasure, or make it pricier or more difficult to acquire, you are doing them real harm

In the US, a full-blown moral panic around e-cigarettes has been orchestrated by fanatics masquerading as public-health professionals. Shamelessly exploiting the deaths of dozens of people killed by contaminated THC oils bought on the black market, politicians and pressure groups have rushed to ban e-cigarette flavourings. The stupidity of responding to a problem in the black market by making more products illegal cannot be overstated. Meanwhile, San Francisco has banned the sale of e-cigarette fluids altogether, as has Australia, Hong Kong, India and Thailand.

Say what you like about the ban on alcohol, but at least it ended. Another legacy of the progressive era, narcotics prohibition, has not. Depending on how you define it, the war on drugs is now either 106 or 108 years old. Its catalogue of failure hardly needs restating. Deaths from illicit drugs recently reached record highs in England and Wales, with deaths from erstwhile ‘legal highs’ – which were banned in 2016 – doubling in a single year. Scotland has the highest rate of drug-related mortality in Europe and now has more deaths from illegal drugs than it does from alcohol. The world is gradually moving in the right direction on cannabis, but it is the outlier. On everything from cigarettes and alcohol, to sugar and vaping, the momentum is with the neo-prohibitionists.

Why does it keep happening? In 1931, the journalist George Ade recalled that ‘[t]he non-drinkers had been organising for 50 years and the drinkers had no organisation whatsoever. They had been too busy drinking.’ There is a lot of truth in this quip. Drinkers, smokers, vapers and people with a sweet tooth are many in number, but lack the incentive and ability to fight back against their puritan foes. They are what economists describe as dispersed interest groups under attack from concentrated interest groups. Ordinary people with lives to lead are no match for highly motivated, full-time, professional pressure groups. The Anti-Saloon League was one of the earliest pioneers of the pressure-group model although, unlike many of its modern successors, it was not funded by taxpayers.

It will not be long before everyone with even the haziest memory of life under prohibition is dead. When they have gone, we may see the history of the era fully rewritten. Those who claim that prohibition was a success will grow in number. They will tell us that everything we know about the period is wrong, that Big Alcohol has misled us with tall tales, and that the noble experiment was a groundbreaking public-health initiative which worked better than you think. Above all, they will say that it is time to give it another shot.

Christopher Snowdon is head of lifestyle economics at the IEA, and author of The Art of Suppression: Pleasure, Panic and Prohibition since 1800. He is also the co-host of Last Orders, spiked’s nanny-state podcast.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.