Long-read

‘The ACLU would not take the Skokie case today’

Ira Glasser says the organisation he once led has retreated from the fight for free speech.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

‘We identified in a way that I don’t think any white kids of our age did with the struggle of a black man against racism’, Ira Glasser tells me, over lunch in an upmarket Manhattan diner.

Glasser, 82, is one of the most important civil-liberties advocates of the past 50 years. He was executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union from 1978 to 2001, helping to turn it into a powerhouse.

He’s also a lifelong campaigner for racial justice, and he’s telling me what is, in effect, his origin story: when Jackie Robinson joined his beloved Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, becoming the first African-American to ‘break the colour line’ and play in Major League Baseball.

Glasser was nine at the time, a self-described ‘street kid’ from a blue-collar, Democratic Jewish immigrant family in Brooklyn. Learning about the racism faced by Robinson ignited his lifelong passion for civil rights.

‘New York had this reputation of being racially and ethnically integrated’, he tells me, in the unmistakable Brooklyn accent. ‘But in fact it was composed of very tight, isolated, segregated, not by law but by custom, ethnic tribes.’

‘So where I lived everybody was white and Jewish, and all of our parents were first-generation Americans, born of immigrants, who came in the early 20th century, mostly from Russia and Poland.’

But then along came Robinson. ‘The Dodgers players were like a priestly class to us, we worshipped them… So we’re rooting for our team, and there’s this wonderful player… And we get embroiled, almost without knowing it, in this racial drama.’

‘Suddenly, these little insulated white boys like me find ourselves in the middle of a passion play’, he says, ‘in the middle of an onstage, highly visible, national drama – what was, in effect, the first major challenge, post-Second World War, against segregation’.

He and his friends found out about racism and Jim Crow listening to Dodgers games on the radio. They learned about the racist barbs Robinson endured and the segregated hotels and restaurants used by the Dodgers when they played around the country.

‘We hated it. And we didn’t hate it because we were civil-rights advocates, we hated it because “you can’t do that to our guy”’, he says. ‘I often joke that if Jackie Robinson had come up at the Yankees, I would have been a racist.’

‘It really was a sociological phenomenon’, he adds, ‘that was not unique to me. When I got to the ACLU, I found there were almost no Yankee fans working there… all the men around my age who grew up in New York, and ended up working at the ACLU, were all Dodgers fans.’

The ACLU was founded 100 years ago last month, but it was during Glasser’s tenure that it grew into a giant. As an ACLU press release put it in 2001, announcing Glasser’s retirement, he ‘transformed’ it from a ‘‘‘mom and pop’-style operation’ to a ‘civil-liberties powerhouse’.

Under his leadership, the ACLU became a truly national organisation, with offices fighting legal cases in every state. And he did all this as a non-lawyer who had a background in mathematics and journalism when he first joined ‘liberty’s law firm’.

But Glasser’s impact was not merely administrative. He helped turn the ACLU into a major force not just for free speech, privacy and due process, and other traditional civil-liberties causes, but also for reproductive freedom, gender equality and racial justice.

Civil rights and free speech

‘When I came into the ACLU there was a distinction that you often heard people make on the national board between what they called civil liberties and civil rights’, Glasser says. ‘I’m very proud of the fact that we restored racial justice to its proper place, high up on our agenda and second to none.’

In fact, it was the civil-rights movement of the Sixties that gave the First Amendment the teeth it has today, says Glasser: ‘The First Amendment had suffered in this country a lot during the McCarthy period, in the Fifties, with all the anti-Communist hysteria. A lot of bad decisions were issued from the Supreme Court.’

‘What revived the First Amendment, in the Sixties, legally, was the civil-rights movement’, he goes on. Challenges to clampdowns on civil-rights marches and demonstrations, he says, ‘created most of the good First Amendment law in the Sixties that resulted in protecting everybody else thereafter’.

The civil-rights leaders of that time recognised how important free speech was to their cause. Glasser tells me about a time he was on TV, defending the ACLU’s defence of Ku Klux Klan members’ First Amendment rights. He was sat alongside Hosea Williams, a black civil-rights leader and lieutenant of Martin Luther King.

The moderator turned to Williams, expecting a counterpoint. ‘And Williams says, on national television, that actually he agrees with me’, recounts Glasser, ‘because if we allow the state of Georgia to interfere with the free-speech rights of the Klan in Atlanta on Monday, they will use that power to interfere with my organising blacks to vote in Fulton County, north of Atlanta, everyday thereafter’.

Freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, he says, were the lifeblood of the fight for racial justice: ‘The civil-rights leaders understood out of concrete experience that the first instrument of change they had available to them was demonstrating and marching and organising.’

But this idea, Glasser laments, is alien to a lot of young people today, who see the ‘First Amendment as an antagonist to social justice’. Indeed, on US campuses ‘progressives’ constantly agitate for right-wing speakers, from Charles Murray to Ben Shapiro, to be banned or forcibly shut them down. ‘Hate speech is not free speech’ is a common refrain.

This turn away from free speech in academia has a longer history than many realise. In the 1990s, hate-speech codes flourished on US campuses. Glasser recalls going to talk to groups of black students at that time who were pushing for racist speakers to be banned: ‘I told them that it was the most politically stupid thing I had ever heard.’

‘All the deans and the president of the university and the board of trustees were all white. They are not your friends’, he says, recalling his advice to them. He’d argue that had such speech codes existed in the Sixties they would have been used most against the likes of Malcolm X and Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver:

‘The only important question in free-speech cases is: who gets to decide? And the answer for oppressed people is: not you. Never you. Never me. Joe McCarthy, Richard Nixon, Donald Trump, Rudy Giuliani, they’re the ones who most often have political power. Why would you want to give them the power to decide who should speak?’

‘The only real antagonist of free speech and social justice is power, political power’, he adds, before offering a neat analogy: ‘Speech restrictions are like poison gas. They seem like they’re a great weapon when you’ve got your target in sight. But then the wind shifts.’

Skokie

Clearly, for all the difficulties we might face today, the principled argument for free speech – even for those we hate, and who hate us – has never been an easy one to make.

We move on to 1977 and Skokie, the ACLU’s defining case. In it, the ACLU successfully defended the right of the National Socialist Party of America – a small group of neo-Nazis led by Frank Collin – to march through a Chicago suburb called Skokie, estimated to be home to 7,000 Holocaust survivors.

Local government filed an injunction and passed ordinances to stop the march from going ahead, and the ACLU took up Collin’s case. At the time, Glasser was executive director of the NYCLU, the ACLU’s New York affiliate. So he was charged with making the case to his members there.

‘In New York, we probably had the largest concentration of Jews among ACLU members than anybody in the country. So I got a lot of shit’, he says. ‘I would go to synagogues and talk about Skokie to Jews who were adults when World War Two happened, who were haunted, either personally or familially, by the Holocaust.’

The way in with people, he says, was to take their fears and their intellect seriously. ‘Jews had good reason to be afraid of people marching around with swastikas… But if you wanted to take that seriously you had to understand that what happened in Germany didn’t happen because there was a good First Amendment there. It happened because there wasn’t.’

Indeed, Weimar Germany had on statute what we would today call hate-speech laws, and Nazi propagandists like Joseph Goebbels and Julius Streicher were prosecuted for their vicious libels of Jews. In turn, they used the attention to promote their cause and pose as martyrs.

When the Nazis eventually came to power, it was state power, not individual liberty, that brought about barbarism.

‘The first time Jews got attacked in the streets by agents of the government or militias that were fronts for the government, there was no constitution to restrain them, or a federal court system that would enforce this’, Glasser says. ‘It was the absence of those restraints that enabled that to rise.’

The Skokie case sparked a national debate, and lost the ACLU members and donations as a consequence. But as it turned out, Skokie became a demonstration of the fact that the best way to challenge hateful speech is with more speech, not censorship.

‘The Holocaust survivor Jews of Skokie organised a counter-demonstration’, recounts Glasser. ‘They had like 60,000 people ready to come march against these 15 people. And in the end, after we won the right for Collin and his group to go to Skokie, they chose not to go, because they would have been completely humiliated.’

The legal argument with Skokie was never in doubt: the ordinances were in breach of the First Amendment. But it was a landmark case in that it burnished the ACLU’s credentials as a principled defender of free speech, not least because many Jewish people worked on the case.

The executive director of the ACLU during this time was Aryeh Neier, a German-born Jew whose family fled Berlin in 1939. His landmark book on the Skokie case bears the powerful title, Defending My Enemy.

For all the flak the ACLU caught over Skokie, it was the ultimate test of principle, and it passed. Fast forward to today, however, and Glasser thinks the ACLU would now flunk that test.

Charlottesville

In August 2017, a mix of alt-right, neo-fascist and white-nationalist groups gathered in the Virginia city of Charlottesville, for what they called the ‘Unite the Right’ rally.

It was sparked by the proposed removal of a statue of Robert E Lee – the Confederate commander – from a local park, but was also intended as a show of strength from the racist right.

Many of them turned up armed, and clashed with anti-fascist protesters. One counter-protester, Heather Heyer, was killed and 19 others were injured when James Alex Fields deliberately rammed his car into her group.

The city had originally tried to revoke the racists’ permit to demonstrate. The ACLU of Virginia was approached by the Unite the Right organisers, and took the case, eventually overturning the ban.

For this, it was immediately accused of siding with bigotry, and after the carnage of the 12 August, of enabling Heyer’s murder: a ACLU of Virginia board member resigned, saying his organisation was ‘defend[ing] Nazis to allow them to kill people’.

Glasser passionately disagrees. ‘The ACLU of Virginia took exactly the right decision’, he says. ‘The descent into violence that occurred in Charlottesville was not a problem of the First Amendment. It was a problem of police incompetence.’

‘You have to vindicate the rights of both [protesters and counter-protesters]’, he says. ‘If anybody gets violent on either side, you gotta bust ’em, for the violence, not the speech.’ In New York City, he adds, this would never have happened, given its long history of policing contentious demonstrations.

At a glance, it might seem that the ACLU held to its principles over Charlottesville, just as it did with Skokie 40 years before it. But the truth is almost the precise opposite: the response of the ACLU leadership to the tragedy was to beat a hasty retreat.

A month after Charlottesville, ACLU executive director (and Glasser’s successor) Anthony Romero told the Wall Street Journal that the ACLU would ‘look at the facts of any white-supremacy protests with a much finer comb’ in future. In particular, it would no longer defend people who intended to march armed.

‘The murder was not committed by the people carrying the guns’, is Glasser’s response. ‘The murder was committed by the guy driving the car. And I never remember the ACLU saying a word when the Black Panthers marched around in the Sixties with guns.’

A follow-up statement from Romero went even further, arguing that ‘the First Amendment absolutely does not protect white supremacists seeking to incite or engage in violence’.

In Europe, where incitement is much more broadly defined, this might sound uncontroversial. But as former ACLU board member Wendy Kaminer pointed out, Romero’s comments amount to support for ‘prior restraints on speech’, something the First Amendment prohibits.

The ACLU against liberty

Things continued to unravel. A year later, Kaminer went public with an internal document, leaked to her by an ACLU staffer, that seemed to urge ACLU members to think twice before defending the rights of racists and fascists.

These guidelines, nodding to the Charlottesville controversy, urged members to take into account ‘the extent to which the speech may assist in advancing the goals of white supremacists or others whose views are contrary to our values’ when selecting cases.

ACLU legal director David Cole has denied that there has been any change in policy. But Glasser is unconvinced. This is all ‘reflective’, he says, ‘of ambivalence and confusion, which adds up to a dilution, a weakening, of the First Amendment advocacy that the ACLU exists for’.

Then comes the killer blow:

‘I believe that the national ACLU, if the Skokie case arose today, would not take it. They might take the same case for the Martin Luther King Jr Association, but they wouldn’t take it for the Nazis.’

As Kaminer has long argued, the rot has been setting in for some time. But since Trump’s election, the ACLU has been more noticeably shying away from contentious free-speech cases.

As a New York Times report put it in 2017, ‘in the first months of the Trump presidency, the ACLU seemed to be more cautious about which fights it would embrace’, adding that it stayed ‘uncharacteristically quiet’ when Milo Yiannopoulos and Ann Coulter were banned by the University of California, Berkeley.

Glasser sees the leadership’s shift as a response to generational change within the organisation: ‘What my successor is doing is demagogic, he’s pandering to what he thinks his new constituency wants to hear. The staff by now must be in their twenties and thirties… They’ve been socialised into a different ACLU.’

Romero may well be pandering to the ACLU’s new supporters, as well. In the wake of Trump’s election, the ACLU began to position itself as part of the anti-Trump Resistance, and it has paid off. Membership quadrupled in a year and online donations alone hit $120million, 25 times what it raised the previous year.

The ACLU has filed hundreds of lawsuits and legal actions against the Trump administration. Many of them are in keeping with the ACLU’s mission, such as those challenging the ‘travel ban’, which it fought on religious-freedom and due-process grounds.

But the ACLU has also waded into partisan political issues, at precisely the same time as it was retreating on First Amendment issues.

‘We will be moving further into political spaces across the country as we fight to prevent and dismantle the Trump agenda’, wrote Romero, in March 2017. Ironically, it was in a piece about the ACLU’s nonpartisanship.

Romero argues that the ACLU’s ‘oppositional stance against this president’ is justified because of the ‘unprecedented threat to our civil liberties’ his administration poses. That’s a contestable position.

But, even so, it doesn’t really justify the ACLU weighing in on the subject of healthcare, as it did in the battles over Obamacare, nor its putting out political ads for and against particular candidates (no prizes for guessing which parties they respectively belong to).

‘I regard all this as tragic’, laments Glasser. ‘Not because an organisation doesn’t have the right to change and say we don’t want to be a civil-liberties organisation anymore, we want to be a progressive, social-justice organisation. It can do that.’

‘But there’s two problems with that’, he explains. ‘One is, while it’s doing it, it’s denying that it’s doing it. It’s being intellectually dishonest. And the second thing is, that there is nothing to replace it.’

‘If Planned Parenthood decided tomorrow to get out of the abortion-clinic business, it would be a blow to reproductive rights. But there are other organisations that take the same position. But there is no other civil-liberties organisation like the ACLU.’

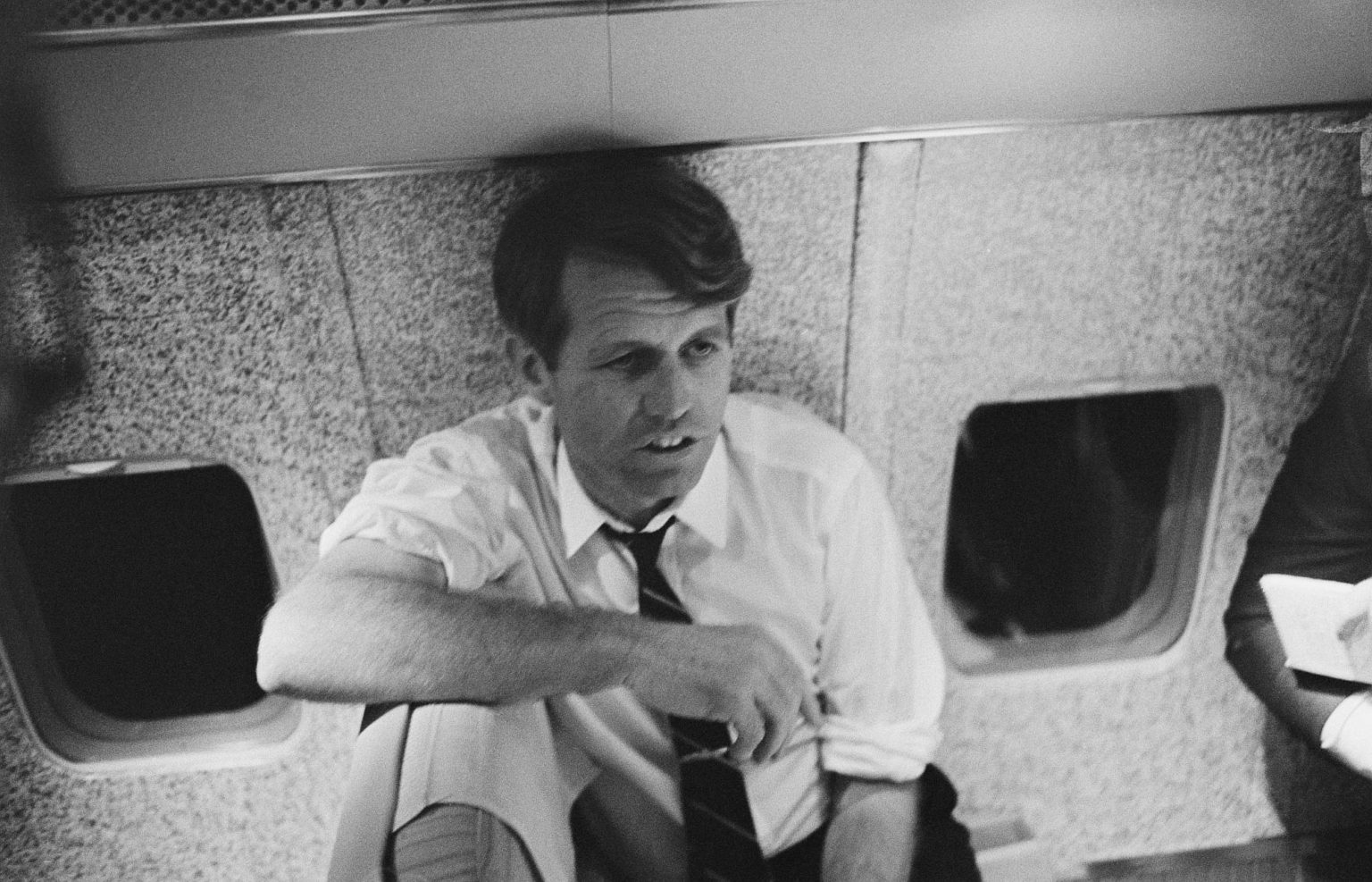

A meeting with Bobby Kennedy

As our lunch draws to a close, Glasser tells me why he decided to take his first job at the ACLU back in the Sixties. And it’s a hell of a story.

Just as Jackie Robinson lit his lifelong passion for civil rights, Bobby Kennedy – brother of John F, former attorney general, and presidential candidate until his assasination in June 1968 – convinced him that the ACLU was an organisation worth working for.

In the mid-to-late Sixties, Glasser, then in his late twenties, was working at a public-affairs magazine, but was hoping to branch into politics. He saw Kennedy as a man who, if he ran for president, could offer hope to a nation roiled by unrest, and he dreamed of one day working for him.

‘I thought, on issues of race and the war in Vietnam, he really got it’, Glasser says. ‘He wasn’t a traditional liberal, in that he had an appeal to the white working class as well as an appeal to blacks… I just thought that he was the most hopeful political future.’

Then, in 1966, Glasser wrote Kennedy an ‘extraordinary letter’, explaining what he saw in him, why he should run for president, and why he thought he could help.

Remarkably, he got a meeting with Kennedy in Washington. ‘I end up having a one-on-one meeting with him for like 40 minutes. As executive director of the ACLU I don’t think I ever had a meeting with a United States senator by myself for 40 minutes.’

Kennedy had not yet decided to run, so there was no role for Glasser. But he urged him to stay in touch, and asked what he might do next.

Glasser mentioned that his friend and former colleague, Aryeh Neier, had offered him a job at the NYCLU. But he had turned it down, thinking the ACLU was too narrow and legalistic for his interests.

Kennedy urged him to reconsider. As Glasser recalls, he said it was a ‘unique organisation in American life’ that ‘represents a radical idea… radical in the sense of going to the root of what the country’s principles and values are really all about’, while still operating through mainstream channels.

‘There’s no other organisation like it… You’re wrong about it being too narrow’, he told Glasser.

Glasser took his advice, albeit with an eye still on politics. In 1968, when Kennedy jumped in the race, he was hoping to join the team. But then Kennedy was shot. ‘It was like the ground was just taken out from under me’, he says.

So he stuck around at the NYCLU. He rose to become executive director, where he learned how to run an organisation, and got involved in the campaign to impeach Nixon after Watergate – ‘another big highlight’, he says. In 1978, when Neier left the national office, Glasser got the top job.

To this day, he credits Kennedy with him ending up in a career he loved. ‘In a very real sense, I don’t think without that conversation with Kennedy that would have happened’, he says. More than 50 years later, he’s still stunned by the insight Kennedy had then:

‘For a guy who was not a traditional liberal, who came out of a kind of autocratic family, who worked for Joe McCarthy, who did not have civil-liberties credentials, to put it mildly… For him to understand what the ACLU was, in a way that I, as a traditional card-carrying liberal from a liberal FDR family, didn’t understand, was really remarkable.’

‘I’ve now reached the age where I’m starting to tell not only history stories, but my history stories’, Glasser jokes, as we get the cheque. ‘It starts with Jackie Robinson and it ends with Bobby Kennedy – those are the bookends. And the ACLU ended up being the job of my dreams.’

Glasser is coming up on two decades of retirement. Though he continues to serve as president of the board of the Drug Policy Alliance, ending the war on drugs being another key cause of his, he devotes much of his time now to his family, the gym, the beach, and of course ball games.

Still, his passion for civil liberties clearly remains undimmed. If only the same could be said for the organisation he once ran.

Tom Slater is deputy editor at spiked. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

Main picture by: Tom Slater.

In-article pictures by: Getty.

Help spiked grow

– become a monthly donor

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.