Long-read

The Nuremberg Trials: fascism as a morality play

They reduced the historical and political horror of Nazism to an act of evil.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Seventy-five years ago, at 10 o’clock on 20 November 1945, the courtroom in the Palace of Justice, Nuremberg, Germany, was crowded. Present were lawyers, generals, soldiers, white-helmeted US military police, photographers, movie cameras, journalists and locals. Punctually, the four judges began the proceedings of the International Military Tribunal.

It was ‘International’ because of the four Allies — America, the Soviet Union, Britain and France. And it was ‘Military’ because they were occupying powers. There was no German government.

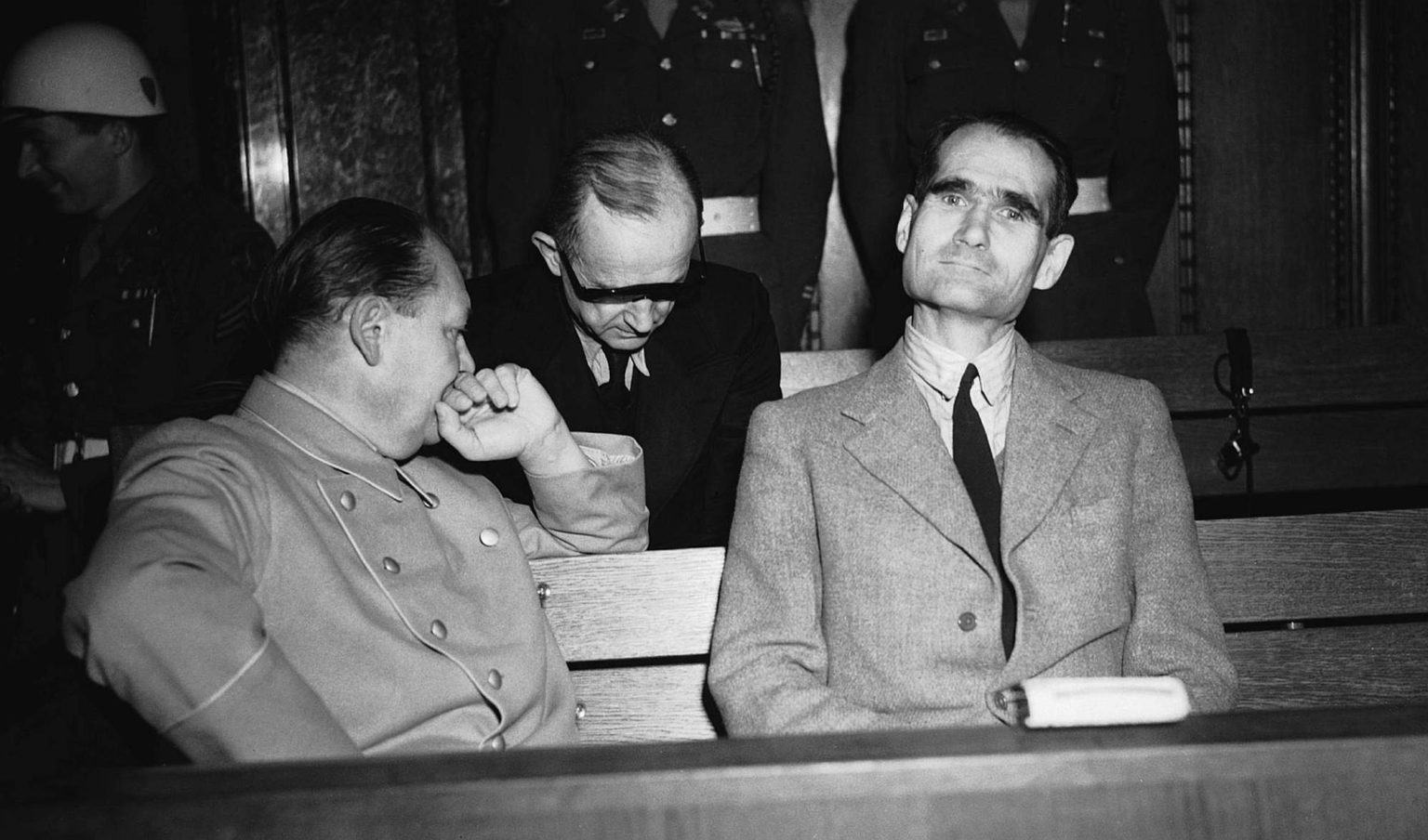

A procession of more than 20 top Nazi officials, led by former Luftwaffe chief Herman Goering, came up from dank, windowless solitary confinement elsewhere in the building, and took to two rows of serried seats. The lights in the panelled room were almost as intense as those shone by each black-helmeted GI as he inspected his own personal captive – known by just a number – in the cells. As we will see, Nuremberg was more than a courtroom drama, a show trial, or the double-standards exercise of victors’ justice. For more than 10 months, the Allies not only saw some kind of justice done there. They also contained the populist and radical worldwide atmosphere of anti-fascism immediately after the war, by making justice seen to be done – in a style more convincing than Stalin’s infamous Moscow Trials. The Allies wanted to make some key political points, of a fundamentally conservative nature, about the postwar order, and to make them in the full glare of the world’s media.

Indeed, that was one reason why they had alighted on Nuremberg as the venue for the Trials. It was the historic seat, with Munich, of Nazism. Nuremberg had been where the architect and wartime Nazi arms chief Albert Speer had organised Hitler’s famously full-on annual party rallies. It was also where Hitler’s deputy, Rudolf Hess, first promulgated the 1935 Nuremberg Laws. These deprived Jews of the right to intermarry and have sex with Gentiles, deprived them of citizenship, and, beyond the Jews, threatened ‘even those who silently distanced themselves’ from the Nazis by their ‘lack of enthusiasm’ with the same lowly status (1).

Now Speer and Hess joined Goering in the rogues’ gallery. The justice dispensed to them in the city with which their infamy was most closely associated almost seemed poetic.

Relevance beyond the legal domain

In Nuremberg, the Allies hoped that a sober judicial ritual would act as a cool riposte to the hysteria that had always surrounded Hitler in this particular city. The Trials were a huge gamble, but, by and large, the Allies pulled it off. They were succeeded by 12 separate trials, from December 1946 to April 1949. These subsequent hearings covered Nazi generals, doctors and judges, as well as ministerial officials and major companies (IG Farben, Krupp) associated with the Nazi regime. Yet, by contrast with the much lengthier International Military Tribunal of the Far East (1946-8), which was held in Tokyo, guided by the same Charter as the Nuremberg Trials, but ‘increasingly fraught with dissension’ (2), the earlier proceedings in Germany were relatively uncontroversial. Why then go back to them now?

One reason is that in Nuremberg we have a template for postwar declarations, principles and conventions that defined much of today’s international law on war. Though times have changed since 1945-6, and the Nuremberg legal approach has been widely and seriously distorted, contemporary international institutions and tribunals on war crimes often still invoke Nuremberg to claim legitimacy.

The legal relevance of the Nuremberg Trials to the 21st century, which has been demonstrated elsewhere on spiked, is not the subject of this essay, however. Rather, it will focus on the politics of Nuremberg as the anti-Nazi climax to the Second World War, and the unique and thus unrepeatable reasons why the Trial succeeded. Paradoxically, it is this very uniqueness which makes it worth understanding Nuremberg’s relevance to today, when memories have faded and times have changed beyond recognition.

Let’s therefore look at the historical run-up to the main Trial, review some key features of it, and assess both its aftermath and its legacy today. First, though, a word on the moral, political and historical distance between the Nazis who were arraigned at Nuremberg and today’s era.

Then and now

That distance is vast. In 2020, it remains important to realise just what those in the dock in 1945, who had outlived the suicides of Hitler, Himmler and Goebbels, had done. It is important because the term ‘fascist’ is used so liberally today to refer to anyone from Donald Trump to President Xi. This completely relativises what happened in the 1930s and 1940s, and obscures the horrific dimensions of the Holocaust.

And the Nazis’ deeds were horrific. At a later Nuremberg trial, Otto Ohlendorf, appointed by SS chief Reinhard Heydrich as commander of the death squads (Einsatzgruppen) in the Ukraine and Crimea, described one feature of Nazi rule. To save money and the feelings of his executioners, the SS developed lorries with airtight space behind their cabs. They were mobile gas chambers, using the exhaust fumes lorries produce to deadly effect. The lorries ‘looked very harmless, so there was no panic when the victims were loaded… there was no excessive stress for the truck driver or his mate, as the engine noise drowned the cries of the dying’. The lorries were equipped with a ‘rapid discharge device’, or tipping mechanism, the more swiftly to unload bodies into freshly dug pits. In October 1941, one engineer noted that no fewer than 97,000 victims were ‘processed’ in just three vehicles, ‘without any faults appearing’. At that time, victims were crammed into lorries at the rate of nine or 10 per square metre. By 5 June 1942, however, the same engineer looked forward to squeezing still more Jews and communists into the same space (3). In Mogilev, Belarus, gassing by lorries took place after midnight, for cover, and lasted just 10 minutes; after it was over, Jewish prisoners would clean the lorry’s space of vomit and faeces, before themselves being shot (4).

At the main trial in Nuremberg, then, crimes against humanity formed the last and most memorable of the four counts against the defendants. The others, in order, were a Nazi common plan or conspiracy, crimes against peace – waging aggressive wars and/or wars that broke treaties – and war crimes, which included: concentration camps and other mass exterminations, mass torture and medical experiments (children included (5)), deportations for slave labour, killing of prisoners of war and hostages, and plunder.

These crimes had not been defined before Nuremberg. Altogether, they formed a rather blurred concept, one which tended to strip the Nazis’ methods of their historical and political context.

But that was just the point. It was not so much fascist politics that were put on trial, but, ironically, humanity itself. As Ann and John Tusa’s old but much-acclaimed account of the Trial has it, ‘It was part of the search for a better way to control strong human impulses, aggression and revenge. It was an attempt to replace violence with acceptable and effective rules for human behaviour.’ At the same time, the left-liberal writer Rebecca West, observing parts of the trial toward its end, opined that its task was ‘to prove that victors can so rise above the ordinary limitations of human nature as to be able to try fairly the foes they vanquished, by submitting themselves to the restraints of law’ (6).

Nuremberg, then, amounted to a juridical attack on evil. To its credit, the tribunal recognised the extraordinarily monstrous deeds of the Nazis. To its discredit, and despite its key charge of conspiracy, it tended to convert the historical experience of fascism into a timeless morality play – indeed, Robert Jackson, the chief US prosecutor, invoked ‘the moral sense of mankind’ in his opening address. The impulse was to portray the Nazi leaders as criminals able to dupe a pliant German population. The focus was on individual sinners, their psychology and their blind group loyalty to Hitler.

That was a travesty worse than the obvious legal travesty of we-make-the-rules victors’ justice. While Nuremberg left Allied mass murder around Hamburg, Bengal, Dresden, Hiroshima and Nagasaki out of account, these events were not its only omissions. Also absent were the class character of the Nazi regime, its drive to destroy the enormous force that had been the German left, and its success, on behalf of capital, in terrorising workers into unprecedented levels of exploitation.

The trial was not just a snow job for the Allies. Over 30 volumes and three supplements of proceedings, 250,000 pages and 775 recorded hours, along with films and photographs, it brought to light the gigantic scale and horror of the Nazi years. At the same time, Allied elites used Nuremberg in the same way as they did D-Day, little more than a year earlier, ‘to neuter radicals, cover over imperial designs, and present imperial politics as progressive’.

Nevertheless, it should be clear that the size, ferocity and duration of Nazi exterminations completely dwarfed anything that might be cast as fascism today. And the historical prelude to Nuremberg, together with the way in which the West used the trial, were quite different from the International Criminal Court, which began life at the Hague in 2002 as a creepy 21st-century imitation of Nuremberg.

The origins of the Trials

The footage and photography of the Nuremberg Trials are mostly black and white, with indicted Nazi leaders wearing headphones, to hear the proceedings by means of a then novel system: simultaneous interpretation. Goering and one or two others are in uniform; the rest, in suits and ties. Sometimes, perhaps because of the bright lights, Goering, Admiral Doenitz and the odd accomplice don dark glasses which, compounded by headphones, make them look spookier than ever. Throughout, Goering is contemptuous, Speer maintains a calm bearing, and Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s party deputy, looks madder and madder.

The fact that top politicians and militarists on the losing side were held in jail, and not under house arrest, was new. Yet these interior scenes were only part of the picture. The pointless Allied bombing of Nuremberg’s quaint old town, which now surrounded the courthouse with rubble, was one sign of the devastation of the Third Reich and the uniqueness of the whole episode. The state of the German working class was another: Rebecca West noted the presence in Nuremberg of ‘a puddle of survivors’ – ‘a frail and scrawny army of old women doing navvies’ work’ to the foundations of ruined buildings (7). And, beyond the immediate vicinity of the trial, its political origins were also very special.

First, in the run-up to the trials, there was much indecision and then unanimity about what to do with the defendants. Three months after the success of D-Day, Roosevelt joined Churchill in initialling a programme drawn up by US Treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau: one which, apart from the impoverishment of Germany, sought simply to identify Nazi ‘arch-criminals’ whose guilt was ‘obvious’, and ‘put them to death forthwith by firing squads made up of soldiers of the United Nations’. But by the time of the Yalta ‘Big Three’ conference in February 1945, Stalin came out in favour of a trial – before, that is, the dispatch of defendants, again by firing squad. The founding of the United Nations at the San Francisco Conference in April 1945 confirmed America’s hegemony in the world and its revised plans to go to trial, which Britain had no choice but reluctantly to accept.

Second, in the light of wider political events, the tribunal was forced to tack toward mass anti-fascist sentiment. A great fear, after D-Day, was that Allied soldiers and others would visit revenge on the remnants of fascism, and so create disorder. There was also a big change in the atmosphere at the tribunal after 19 February 1946, when the Russians showed a one-hour compilation film of Nazi atrocities. Made by Elizaveta Svilova, the collaborator and wife of the famed director Dziga Vertov, the film unexpectedly transformed the court. Among other terrible sequences, it showed how naked Polish women were made to lie down in mass graves before being shot. Afterwards, the perpetrators are seen smiling for the camera.

Third, political priorities demanded not only an accommodation to the Soviets, but also a mass lesson, in the West, in anti-Communism. The appointment, in May 1945, of the arch Tory MP and lawyer Sir David Maxwell Fyfe as head of the British prosecuting team was a move towards this end. Thus the conservative texture of the trial was assured.

Then, at the Potsdam conference of the Big Three in July, 1945, new US President Harry Truman and Churchill learned that US scientists had successfully exploded an experimental atomic weapon. That emboldened them against the Soviets (8), as did the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki early the following month. After that, little more than three months passed after the opening of Nuremberg before Churchill was ready to give, on 5 March 1946 at Fulton, Missouri, his famous ‘Iron Curtain’ speech against Russia.

In Britain, Mediterranean Europe, Asia and the US, serious class struggles attended the aftermath of the war. Democracy was widely restricted. The Allies therefore had both to come to terms with Russia’s expansion westward and the international left’s wartime prestige, while also stigmatising Communism. But at Nuremberg that didn’t prove difficult. When the Russians falsely alleged that the German army had murdered thousands of Polish officers at Katyn wood, near Smolensk, about 200 miles west of Moscow, the tribunal let the defence team demolish the Soviet claim over two days – hinting in the process that the allegations were a cover-up for a massacre the Russians had themselves organised.

What, then, could the left ever do about Nuremberg? It surely wanted to avenge itself on the fascists. But was it not also in a position to suggest that Allied leaders themselves be put in the dock for assorted bestial acts? No, it was not. Given its unalloyed support for the war as a left-wing cause, and after the courtroom quarrel over the Katyn massacre and the strong suspicion that the Russians had been responsible, the left could only acquiesce to the trial, and to the framework it provided for postwar international relations.

In this respect Nuremberg, with all its trappings, proved an effective weapon against socialism in the mid-20th century. It took the whole nine yards of fascism, reduced them to man’s inhumanity to man, and depoliticised them.

Psychology and the personalisation of politics

Nuremberg was not just a victory for lawyers over politics. It was also where the character analysis beloved of a burgeoning wartime discipline – psychology – came into its own (9). Thus prosecutor Jackson reminded Hjalmar Schacht, appointed by Hitler as Reichsminister of economics in 1934, of the opinion about Goering that he had shared with British intelligence interrogator Major Edmund Tilley. According to Schacht, Goering was:

‘Endowed by nature with a certain geniality which he managed to exploit for his own popularity, he was the most egocentric being imaginable. The assumption of political power was for him only a means to personal enrichment and personal good living. The success of others filled him with envy. His greed knew no bounds. His predilection for jewels, gold and finery, et cetera, was unimaginable. He knew no comradeship. Only as long as someone was useful to him did he profess friendship.’

This was an early and influential form of the personalisation of politics that so afflicts what passes for political critique today. It rests on the assumption that politics can be reduced to and explained away by an individual’s putative psychopathology. So it is notable that both Schacht, a placeman for the Nazis, and Jackson took this psychological explanation of Goering as good coin.

That was not by chance. Lieutenant colonel Douglas Kelley, a US Army military intelligence officer who served as chief psychiatrist at Nuremberg, claimed to have spent no fewer than 80 hours with each of the prisoners he assessed. US Army first lieutenant Gustav Gilbert, a Jew with flawless German, was also appointed psychologist to the prisoners.

Before and during the trial, the two men played soft-cop listeners to the defendants in their confinement, with Gilbert using the results to help guide Jackson with his case. Like Jackson in court, Gilbert coached Speer in his cell. That way Speer’s acceptance, at the trial, of personal and collective responsibility for fascist misdeeds could undo Goering’s combative oratory for and leadership of those in the dock, and work to the Allies’ maximum advantage.

Interestingly, Kelley and Gilbert also administered the newly trendy Rorschach inkblot test to the defendants. ‘Psychiatry and psychology’, in the words of one Californian academic,

‘were oddly central to the trial in ways that are largely forgotten. First of all, the trial was not so much “who done it” as it was a “why did they do it”…. This was an enormous and unusual effort in the history of medicine. Never before, have we studied so closely leaders who had steered a country into such an abyss.’

Indeed, never before had inkblot marks on a piece of paper been used to provide an explanation of barbarism.

The rise of psychology in the war had, back in June 1945, allowed American professional associations dedicated to mental deficiency, neurology, psychiatry and unrelated disciplines to write a letter to Jackson saying that ‘detailed knowledge of the personality of these leaders… would be valuable as a guide to those concerned with the reorganisation and re-education of Germany’ (they also wanted dead defendants to have their brains examined). Significantly, General William J Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services (forerunner of the CIA), backed the letter – and the Rorschach tests. But then the shrinks got another break.

If, at the trial, Rudolf Hess could be proved to be as dotty as he increasingly appeared to be, his fitness to stand, and the prestige of the trial itself, would come into question. Therefore much depended on the shrinks’ verdict on the mental state of Hess: was he faking or not? When Hess owned up to faking it, all was well. But for the opening 10 weeks of the trial, ‘a steady flow of stories’ from Gilbert ‘continued to be a staple of press coverage’ (10).

Once again, and despite the charge of conspiracy, the politics of Nazi rule were reduced to egocentrism and other personality disorders.

Conclusion: the Nuremberg moment

There is much more we could say about the main trial at Nuremberg, the sentences passed on individuals and the hypocrisy of Britain and America. For instance, the Allies let all the SS Cavalry (the Reiter SS, which was very active on the Eastern front) and plenty of lesser fascists off the hook and into significant positions in postwar Germany (11).

However, we can sum up the impact of Nuremberg simply enough. It is still lauded as an eternal model for how the ‘global community’ should deal with national dictators. It was preceded by the UN’s hope that ‘respect for international law’ could ‘save succeeding generations from the scourge of war’. And it was succeeded, in 1950, by the UN’s seven Nuremberg Principles, which hold both heads of state and juniors ‘following orders’ to account for their deeds in wars (12). Yet the overall and time-bound social legitimacy of the trial should warn us against attempts, made 75 years later, to repeat it. Conditions now are very different from Nuremberg: any international court on wars can rely on much less cohesion or popular support.

More broadly, a review of the film The Meaning of Hitler (2020) by the hip independent filmmakers’ organ IndieWire can, rather oddly, serve as an index of the political mystification Nuremberg helped achieve. Critic Eric Kohn agrees with the movie’s directors that ‘fascism can happen anywhere’ – indeed, that ‘the fascism of the past can happen just as easily today’. He agrees also that ‘normal people did awful things’, though he concedes that observation ‘doesn’t exactly unearth new insights into the nature of the Third Reich’. Oh, and of course society ‘remains vulnerable to the same complaisant attitudes’ exploited by Adolf Hitler ‘decades ago’.

There we have it. Instead of political analysis of fascism, we get glib, liberal platitudes about the universal human potential for… deviancy. Instead of understanding what fascism did to the working class, we get a swipe at the perennial gullibility of the masses.

These are the anodyne but actually very bitter fruits of the Nuremberg moment.

James Woudhuysen is visiting professor of forecasting and innovation at London South Bank University.

Main picture: Getty.

(1) The Third Reich in Power, 1933-1939, by Richard Evans, Penguin Press HC, 2005, p544

(2) ‘The Tokyo and Nuremberg International Military Tribunal Trials: a comparative study’, by David M Crowe, in The Tokyo Tribunal: perspectives on law, history and memory, edited by Viviane E Dittrich, Kerstin von Lingen, Philipp Osten and Jolana Makraiova, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2020, p59

(3) Data and quotations from Justice, not Vengeance [1989], by Simon Wiesenthal, Mandarin, 1990, pp71-2

(4) Hitler’s Death Squads: The Logic of Mass Murder, by Helmut Langerbein, Texas A&M University Press, 2003, pp115-116

(5) On 19 February 1946, page 8 of the New York Times reported from Nuremberg. ‘I often saw an executioner taking children by the feet, tearing them apart and throwing them into the fire’, said one witness. The reporter, Drew Middleton, went on: ‘The extermination of children was general throughout occupied Russia. Besides the 5,000 children killed in Riga, thousands more were slaughtered in Orel, Kiev, Stavropol, Brest-Litovsk and a thousand unknown villages. Some were drowned in the sea off Stavropol; others were killed experimentally in gas chambers; thousands were thrown into graves and buried alive.’

(6) Both quotations from The Nuremberg Trial, by Ann Tusa and John Tusa (1983), Papermac, 1984, p14

(7) Rebecca West, Foreword to Nuremberg: a personal record of the trial of the major Nazi war criminals, by Airey Neave, Coronet Books, 1978, p7. At the end of the war, the average weekly pay of a semi-skilled German worker was 80 RM [Reichsmarks], a sum made equivalent, in 1948, to eight Deutschmarks. Before that, the black market ensured that ‘a one-dollar carton of cigarettes retailed at 1000 RM or more’. See The Germans (1982) by Gordon A Craig, Penguin Books, 1984, p122

(8) Shattered peace: the origins of the Cold War and the national security state, by Daniel Yergin, Andre Deutsch, 1978, pp120, 121

(9) On the wartime rise of US psychology, see ‘Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders’, by James Woudhuysen, The Academy Online, 20 June 2020, 11 minutes in

(10) The Nuremberg Trial, by Ann Tusa and John Tusa (1983), Papermac, 1984, p214

(11) On the arbitrary and repressive nature of the ‘DeNazification’ of post-war Germany, see An Unpatriotic History of the Second World War, by James Heartfield, Zero Books, 2012, pp388-390. Though overly pessimistic about a fascist revival – more than a decade after The Times, in 1950, had declared Germany a Wirtschaftswunder, or economic miracle – The New Germany and the Old Nazis, by the German journalist T H Tetens, Random House, 1961, is factually useful on fascists employed by the postwar West German state, and the role of Konrad Adenauer in creating the environment for that to happen. See in particular pp63, 65, 98, 102, 205

(12) Yearbook of the International Law Commission 1950, Volume II: Documents of the second session including the report of the Commission to the General Assembly, United Nations, 1950, pp374-378

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.