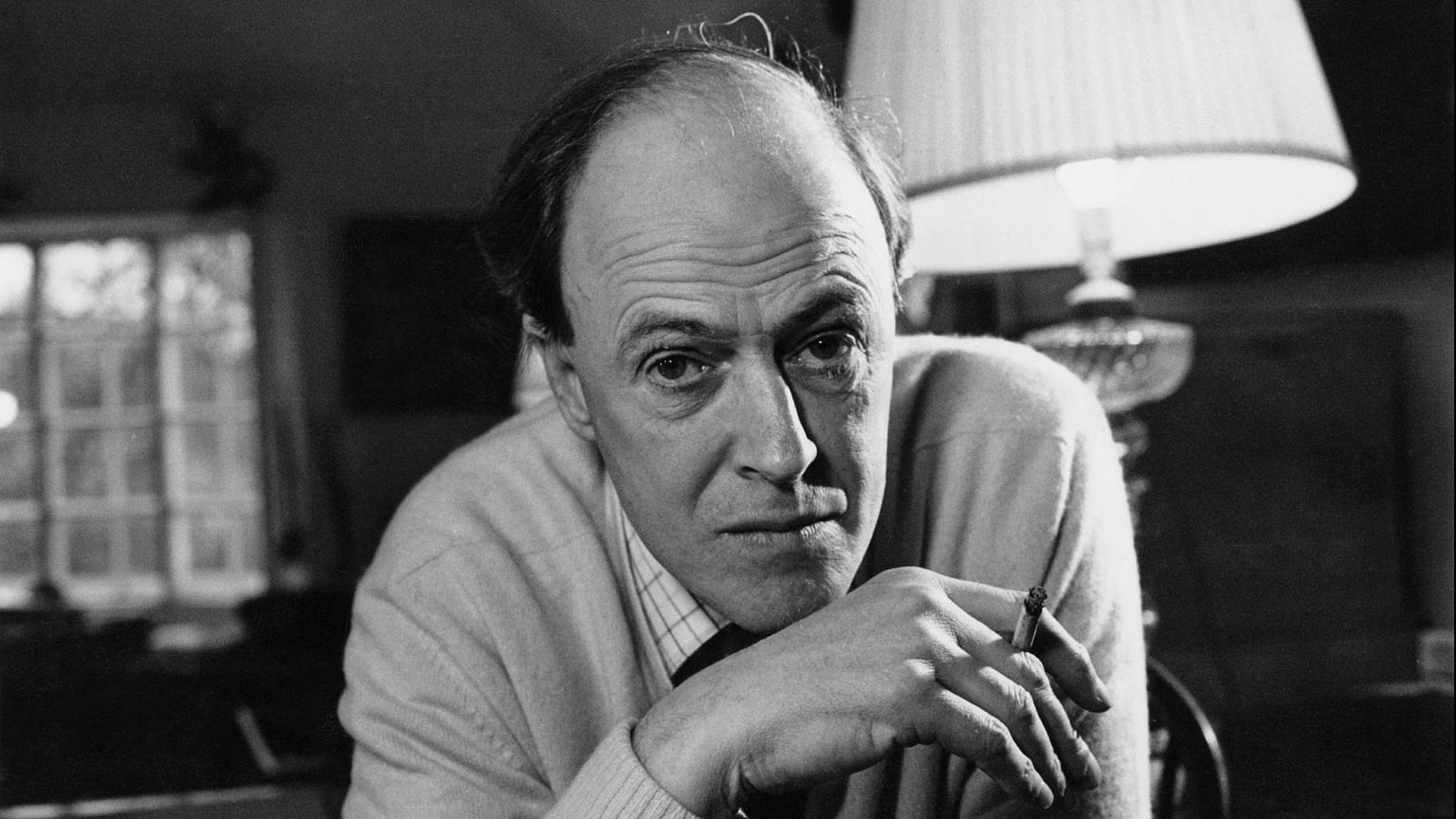

Why is Roald Dahl’s family apologising for his racism?

His anti-Semitic comments were horrendous – but his family has nothing to be sorry for.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Some years before I was even born, the beloved children’s author Roald Dahl made racist comments about Jewish people in two interviews. He spoke of ‘a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity’ and even accepted he had ‘become anti-Semitic’.

Pretty abhorrent stuff, to be sure.

Now, The Sunday Times has noticed that, hidden away in an unobvious part of the late writer’s website, there is a statement about Dahl’s unsavoury views. It reads: ‘The Dahl family and the Roald Dahl Story Company deeply apologise for the lasting and understandable hurt caused by some of Roald Dahl’s statements.’ It criticises them as ‘prejudiced remarks’ which ‘stand in marked contrast to the man we knew’.

The Campaign Against Anti-Semitism says the apology should have come sooner. In truth, it need not have come at all.

Dahl’s comments were, indeed, prejudiced. Were he still alive, and had he changed his views and written a similar statement of apology, it would have made sense. But Dahl has been dead for 30 years, and this statement was produced by others, with no connection to what he said.

The statement, then, is very strange. Why did Dahl’s family – and the company bearing his name – feel the need to apologise for the views of their dead ancestor?

It is perhaps understandable that the company wanted to acknowledge the comments he made, rather than pretend they did not happen. But there was no need for them to say sorry. Dahl’s bigoted views were his own, not those of his family or the company.

How do we explain this stark act of unnecessary self-flagellation?

The answer has much to do with the nature of contemporary discourse about racism. Thankfully, great progress towards some of the primary goals of anti-racist movements has been achieved. There is still work to be done, but the UK, at least, is far less racist than it was a few decades ago. Unfortunately, though, mission creep has set in among a new generation of activists.

Struggling to find evidence that society really is as racist as they say, activists have started to focus on more ethereal, subjective conceptions of bigotry. In recent years, this has been manifested in discussions about ‘white privilege’.

A sorry consequence of this shift is that, today, innocent people are judged for the sins of their fathers. Contemporary activists implore us to recognise how we benefit from the racist actions of our ancestors, and the oppressive systems they constructed. They lecture us about our unconscious biases, and tell us we will never be totally free of them, so essential are they to our make-up. And they let us know in no uncertain terms that if we are not actively fighting racism in the precise way they demand, then we are part of the problem (‘silence is violence’, we are told).

In the face of such wild generalisations and accusatory tactics, some people have judged it better – morally, strategically or otherwise – to accept responsibility for things they are clearly not to blame for.

Some institutions have sought to publicly acknowledge historic connections to the racist past even when these have little relevance to the present. For example, the British Library has made an incredibly tenuous link, recently adding the late poet Ted Hughes to its dossier documenting links to slavery and empire in its collections. The reason? One of Hughes’ ancestors, born in 1592, was involved in colonialism in North America.

And now, the family of a deceased literary legend has apologised because he was racist.

It is unclear whether the family and the company apologised for Dahl’s comments because they genuinely thought such an action was morally necessary, or because they feared the consequences if they failed to act. An understandable desire to avoid controversy may well have provoked the move — that would explain the fact that the apology was not put front-and-centre on the website.

Indeed, a pre-emptive move to prevent a possible future ‘cancellation’ of Dahl would make sense in purely PR terms. But the act itself implies the legitimacy of the idea of inherited guilt. It suggests that blame for bigotry really does run in the blood, and is passed on in some bizarre way from one generation to the next. This itself is a product of a political culture in which we are encouraged to identify people primarily by their ethnic and cultural backgrounds, rather than by their actions or beliefs.

If we are to be blamed when our fathers say or do bad things, then it stands to reason that we should shoulder the burden not just of their prejudices but also their other errors in life. If they rack up enormous debts, we should be obliged to take them on. If they commit crimes, we should pay the price for them. And if they do anything that upsets the woke crowd, we must bend our knee and beg for forgiveness on their behalf.

No thanks. We are not our fathers. We are not our ancestors. We are ourselves, and we must be allowed to make our own way in the world, without being held responsible for those who went before us.

Paddy Hannam is a spiked intern. Follow him on Twitter: @paddyhannam.

Picture by: Getty Images.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.