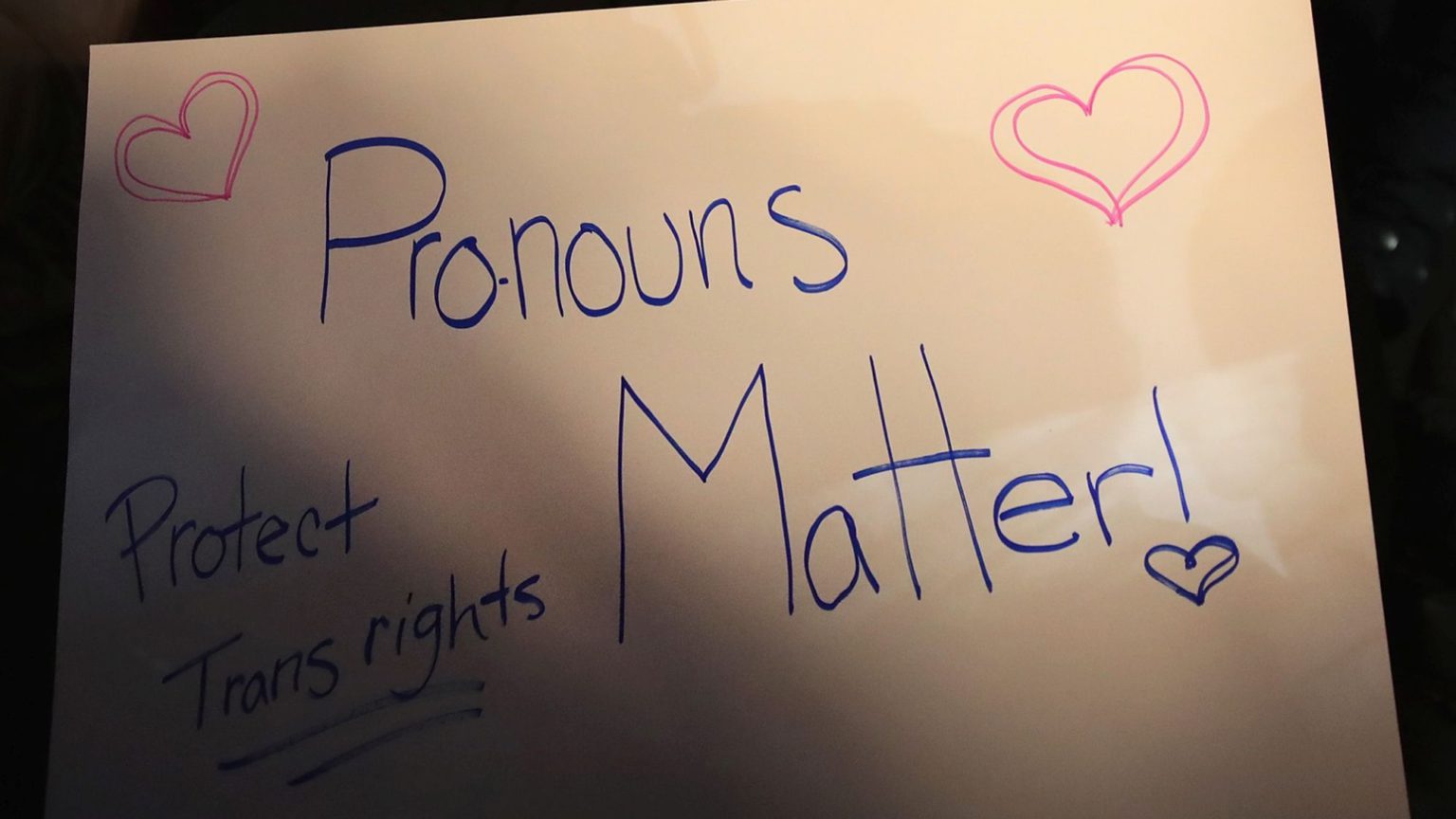

Beware the proliferation of preferred pronouns

Pronouns can’t be mandated from above. But that hasn’t stopped the pronoun police from trying.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

I recently attended an online conference on student mental health and was struck by the number of attendees whose online identification included not only their name but also their preferred pronouns. There is a growing trend for people to list their preferred pronouns on their social-media profiles and on their personal or work email signature. The third Wednesday in October each year is now International Pronouns Day. Many celebrities and politicians have also got in on the act. Former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, in an address at the Pink News awards, introduced himself by declaring that ‘my pronouns are he/him’. For many, these declarations not only express their personal identity, but are also meant to denote their alignment with progressive and subversive political causes.

The politicisation of pronouns is in and of itself not new. People have been searching for gender-neutral pronouns since at least the 18th century as pronouns have played a role in the establishment of our rights and identities. Legislation invariably used male pronouns, and debates ensued over whether the legislation was gender-specific or encompassed both sexes.

John Stuart Mill, the 19th-century philosopher and politician, introduced an amendment to a parliamentary bill that sought to replace ‘man’ with ‘person’ to ensure no ambiguity over its application to both men and women. This was a time when most legislation used ‘he’ and ‘him’ and raised the obvious question as to whether the laws of the land applied only to men or included women. In other words, was ‘man’ universal or gender-specific? The answer to this question depended on the context. In terms of the right to vote or to practise law, it was deemed to be gender-specific, with such rights only applicable to men. But in laws relating to such things as crime and taxation, it was held to refer to both genders.

Initially, women invoked the generic use of ‘he’ to assert the right to vote, while their opponents asserted that ‘he’ did not include ‘she’. Later on, the generic ‘he’ and gender-neutral ‘man’ became the target of feminists. We have also seen the rise of gender-neutral job titles such as firefighter, headteacher and chairperson.

The search for a gender-neutral pronoun has also concerned many writers. The singular ‘they’ – the use of which brings many grammarians out in a cold sweat – features in the work of Jane Austen (over 70 times in Pride and Prejudice), William Shakespeare and Charles Dickens.

In What’s Your Pronoun? Beyond He and She, Dennis Baron, emeritus professor of English at the University of Illinois, discusses these developments, charting how we got from ‘he’ and ‘she’ to ‘zie’, ‘hir’ and singular ‘they’. Baron points out that while many alternatives have been proposed over the years, most fall into obscurity as the public fails to accept or use them. This leads him to conclude that ‘laws mandating pronouns don’t work: people use the pronouns they like, not the ones they’re told to use’.

So is today’s proliferation of public declarations merely a resurgence of a centuries’ old concern? Not quite. Most obviously, the concern today is not about whether ‘man’ includes both sides of the male/female binary — it is about the rejection of the binary altogether. It is not about a universal signifier but about signalling personal identity, moral status and political identification. There are more concerning aspects to the pronoun debate, too.

Baron may be correct when he says that pronouns cannot be mandated from above. But this has not stopped the pronoun police from trying. Brighton and Hove City Council has a ‘my pronouns are’ campaign which encourages people to wear badges indicating their preferred pronouns, warning that ‘making assumptions can be hurtful and distressing’. Many universities’ student unions now distribute ‘pronoun badges’ for their students to wear. According to the police, failing to respect a person’s self-declared pronoun can be a form of abuse and may even be deemed a hate crime.

The main concern in the past was with the way pronouns could be used to disenfranchise a group of people from the right to vote and from employment, turning some into second-class citizens. Today’s campaigns have a more individualist focus; the intention is to achieve recognition as a unique and vulnerable individual, as can be seen in the smorgasbord of pronouns that are available to choose from, and how failure to use a person’s individual preference is said to be deeply hurtful to them. It is a demand for our feelings to be protected by the state.

The public exhibition of one’s preferred pronouns is also intended to signify the moral sensibilities of the individual. Those who declare their pronouns are advertising their awareness, unlike the unenlightened mass of people who fail to declare. In this sense, the public presentation of pronouns is akin to the wearing of a crucifix in a more religious age, or the wearing of badges or ribbons in the current one. In each case, the intention is to signify adherence to the cause and demonstrate to the world your moral status. The pronoun is merely a means to an end.

Of course, just as people are free to wear the old religious symbols, so they should be free to advertise their commitment to contemporary orthodoxies. But when politics becomes focused on pronouns, this can only be because it has been stripped of any wider social, political or historical significance. Political action has been replaced with a demand for personal recognition.

Ken McLaughlin is a senior lecturer in social work at Manchester Metropolitan University. He writes here in a personal capacity and his views are not necessarily those of his employers. His latest book, STIGMA – and its discontents, is due for publication in 2021.

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.