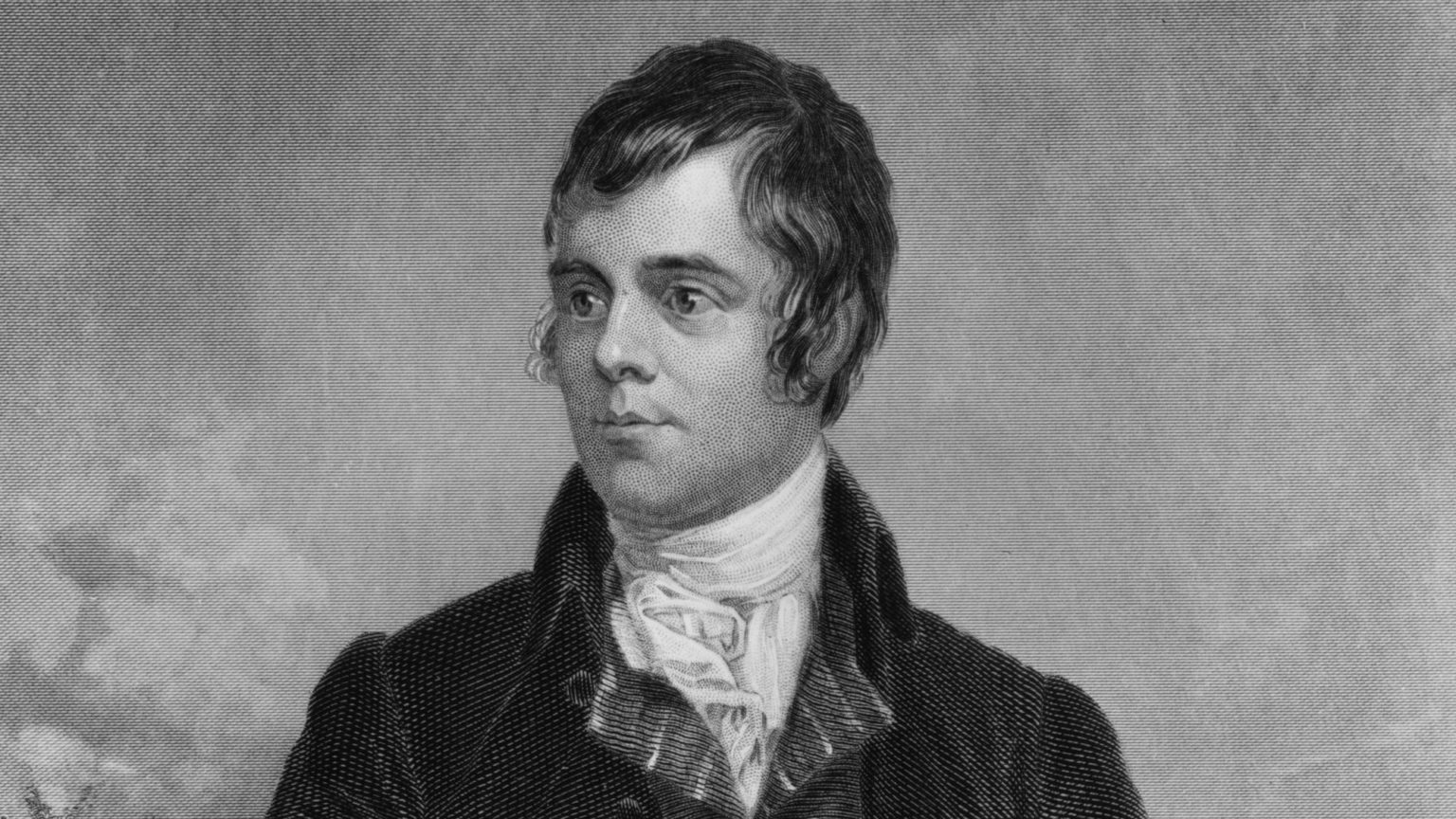

Robert Burns: poet, fornicator and rebel

The bard is still enraging an uptight Scottish establishment.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Even the lockdown was not going to stop this year’s Burns Supper celebrations. In fact, it may well have been the biggest ever, as thousands upon thousands of Robert Burns fans across the globe toasted the bard via Zoom.

But not everybody came to praise the Ploughman Poet. Appearing on Sky Arts’ Robert Burns: No Holds Bard, Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon lamented that his great poem, ‘A Man’s a Man for A’ That’, should have been written as ‘“A Person’s A Person”… or something like that’, in order to better reflect the values of modern-day Scotland.

The hour-long programme was hosted by poet and playwright Liz Lochhead, who seems to have long had it in for Burns. In a lecture in 2018, she drew attention to a letter Burns penned in 1788 to his friend Robert Ainslie, in which he bragged at length about his sexual relationship with his lover, Jean Armour. Lochhead slammed Burns as ‘Weinsteinian’ and a ‘sex pest’. In the letter, Burns boasts that he ‘fucked her until she rejoiced’ and ‘electrified the very marrow of her bones’. But in Lochhead’s imagination, Burns’ ‘disgraceful sexual boast’ sounded like the description of a sexual assault, in which Armour’s ‘exclamations of pleasure may well have been cries of pain’.

Lochhead is far from alone in her revisionist readings of Burns. Writing in the Guardian in 2017, critic Stuart Kelly said it was time to end Scotland’s sentimentalised celebration of Burns. Again, the notorious 1788 letter was apparently evidence to convict Burns as a ‘rapist’.

Burns was indeed very sexually active – a notorious fornicator who fathered some 13 children. But there is, of course, no actual evidence to suggest that he was a sexual predator, beyond the spurious claims made from unapologetically presentist readings of his work. These accusations spurn historical context in favour of the divisive identity politics that shape contemporary Scottish public life.

In fact, the Scottish establishment has always had a problem with Burns, his sexuality and his politics. He has long been the fly in the moralist’s ointment. In 1785, Burns was hauled before the Ayrshire Kirk sessions and publicly humiliated for immoral fornications with his lover. The Kirk of the Scottish Presbyterian Church was an oppressive social and moral force in Scotland. Scotland’s feudal landowning class used it to police the private behaviour of its tenant farmers and their families.

In response, Burns penned what is now considered his greatest satirical poem – ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ – which was published anonymously in 1789. This burlesque takes the form of a fictional prayer by the eponymous Willie Fisher – a real Kirk elder – asking God for forgiveness for his own sins, while demanding punishment of the same transgressions of those not so godly as he. Written as an attack on the hypocrisy of religious theology and its oppressive hold on Scottish society, ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ also illustrated Burns’ deep anti-authoritarianism and commitment to personal freedom. This is what makes Burns such a thoroughly prescient poet.

Burns identified strongly with the cause of the American and French Revolutions. During this period he was at his most radically Jacobin. The revolutionary values and democratic principles articulated in Burns’ work became central pillars in the populist and anti-aristocratic movements that came to enjoy support among ordinary Scots well into the 19th century, which would help loosen the oppressive hold of Scotland’s landed aristocracy.

Written in 1795, Burns considered his poem, ‘A Man’s a Man for A’ That’ as Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man in verse form. Published in two parts in 1791 and 1792, Paine’s treatise was a defence of the French Revolution, and an attack against the notion of hereditary rule – ideals that were to feature foremost in Burns’ work. In a deliberate echo of Paine, Burns’ ‘The Rights of Women’ concludes with the Jacobin cry ‘Ah! Ça ira!’’, referencing a revolutionary song that called for the end of hereditary and clerical power.

As Jacobin ideals spread across Europe, Scotland’s feudal elite, aided by the reactionary Scottish judiciary and a morally prurient clerisy, unleashed a wave of repression. Press freedom, free speech and freedom of assembly were all attacked. In late 18th-century Scotland, Burns’ radicalism made him an obvious threat. In our modern, censorious political culture, Burns’ anti-authoritarianism is just as subversive as it was in his day.

Burns is one of many white, male Scottish historical icons to have fallen foul of Scotland’s culture warriors. In September, Edinburgh University sought to distance itself from Enlightenment thinker David Hume by claiming he was a racist. Similar accusations have been levelled at historian Thomas Carlyle and other figures of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Burns has not escaped the ‘racist’ tag, either. In 1785, just prior to the publication of his first work, Poems, a poverty-stricken Burns considered emigrating to the West Indies to take up a position on a slave plantation. In a recent BBC documentary, Scottish novelist Andrew O’Hagan said this was ‘inexplicable’ and ‘the one thing that… could cause us to question his integrity’. O’Hagan concludes that Burns was ‘not as principled as I would want him to be’.

Providence intervened when the publication of Poems made Burns a national celebrity. Instead of charting a course for the Caribbean, he set sail for Edinburgh, Scotland’s intellectual epicentre. The desire to attack Burns for merely considering working on a slave plantation clearly illustrates the anti-historical thinking that now shapes Scotland’s cultural landscape. The new cultural clerisy goes to extraordinary lengths to taint the Enlightenment ideals that Burns’ poetry gave voice to, and which, until recently, gave shape to a sense of a shared, common Scottish identity.

If Burns had taken up the post, he would have been just one of many Scots prepared to consider a career in the slave plantations of the British Empire. The crippling poverty and oppressive social order that marred 18th-century Scotland forced thousands of ordinary people to seek better lives elsewhere. Given its centrality to the Scottish economy, the slave plantations of the Caribbean were very often the only choice people had. That this was their best and only option is an indictment of the backwardness of the Scottish economy and its social order, not of the character of those who struggled and fought to make a better life for themselves.

By reinterpreting Robert Burns through the prism of modern identity politics, Scotland’s cultural elites not only sully his legacy, they also give voice to the prejudice that sits at the heart of contemporary Scottish politics – that ordinary Scottish people have little in common besides their bigotry.

It is this same prejudice that informs divisive and punitive initiatives like the Scottish government’s Hate Crime Bill. The suffocating hold of the Kirk lives on through the identitarian politics of the Scottish establishment. If there was ever a political culture that embodied everything Burns and his Jacobin contemporaries railed against, this is it.

Long may we continue to celebrate the genius bard and raise a glass or two every January to the chieftain of the pudding race. We should celebrate his efforts to liberate himself and his community from the suffocating moral pruriency of an oppressive elite. Some 225 years after his death, Robert Burns still continues to prick the moralising sensibilities of his social betters. This is the real power of his legacy, and why he is as relevant today as he was in 18th-century Scotland.

Carlton Brick is a lecturer in the school of education and social science at the University of the West of Scotland.

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.