The Tokyo Trial: a hollow victory for US imperialism

It exposed as much about Western racism as it did Japanese war crimes.

Seventy-five years ago, the Tokyo Trial began. Also known as the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, and formally as the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), it was set up to try 28 senior Japanese admirals, generals and officials for an assortment of crimes committed during the Second World War.

Few in the West remember, let alone comment on the trial today. Its anniversary has had almost no media coverage, even if it was earlier the subject of an excellent Netflix docudrama, Tokyo Trial (2016). Yet, 75 years on, this trial deserves our attention. Not least because its impact can still be felt today.

On 21 April this year, Japanese premier Yoshihide Suga flaunted his disagreement with the guilty verdicts and seven hangings dictated by the IMTFE. He sent a ceremonial offering to the Yasukuni Shrine in Chiyoda, Tokyo, where several ‘Class A’ Japanese war criminals, so designated by the verdicts of the IMTFE, are buried. Suga’s gesture ‘predictably angered’ Beijing and Seoul, since Chinese and Koreans retain bitter memories of Japanese occupation before and during the Second World War.

The Tokyo Trial lasted from 3 May 1946 until 12 November 1948. It generated a 48,000-word transcript and a 1,200-page majority judgment made by seven of the 11 judges, who were drawn from 11 nations. Of the 55 counts brought against the defendants, no fewer than 45 were dismissed.

Yet, floodlit for filming, the trial was never a purely legal affair. Rather, it was a political event that was to shape the development of postwar Japan.

A Pyrrhic victory?

The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, first and foremost, marked the political subordination of Japanese to American imperialism, formalising the doctrine of Japanese war guilt. In doing so, it sought to exonerate America and Britain for their colonial and racial exploits before and during the war – and for their use of atomic weapons at the end of it. Thanks in part to the Tokyo Trial, Japan remains a junior, non-nuclear partner to America today.

The IMTFE also exposed the racist aspects of the West’s behaviour in the Asia-Pacific. Although the trial recounted stomach-churning interwar and wartime Japanese attacks on the Chinese and others, it also highlighted, thanks to its Japanese and American defence lawyers, clear double standards on the part of the white West. As a result, the Tokyo Trial emboldened the postwar Japanese right, and proved to be a political blow from which, in Asia, America has never entirely recovered.

The Tokyo Trial was thus a Pyrrhic victory for the Americans. It let slip the veil that Washington and the West wanted to draw over their racial record in the Far East.

Notable absences

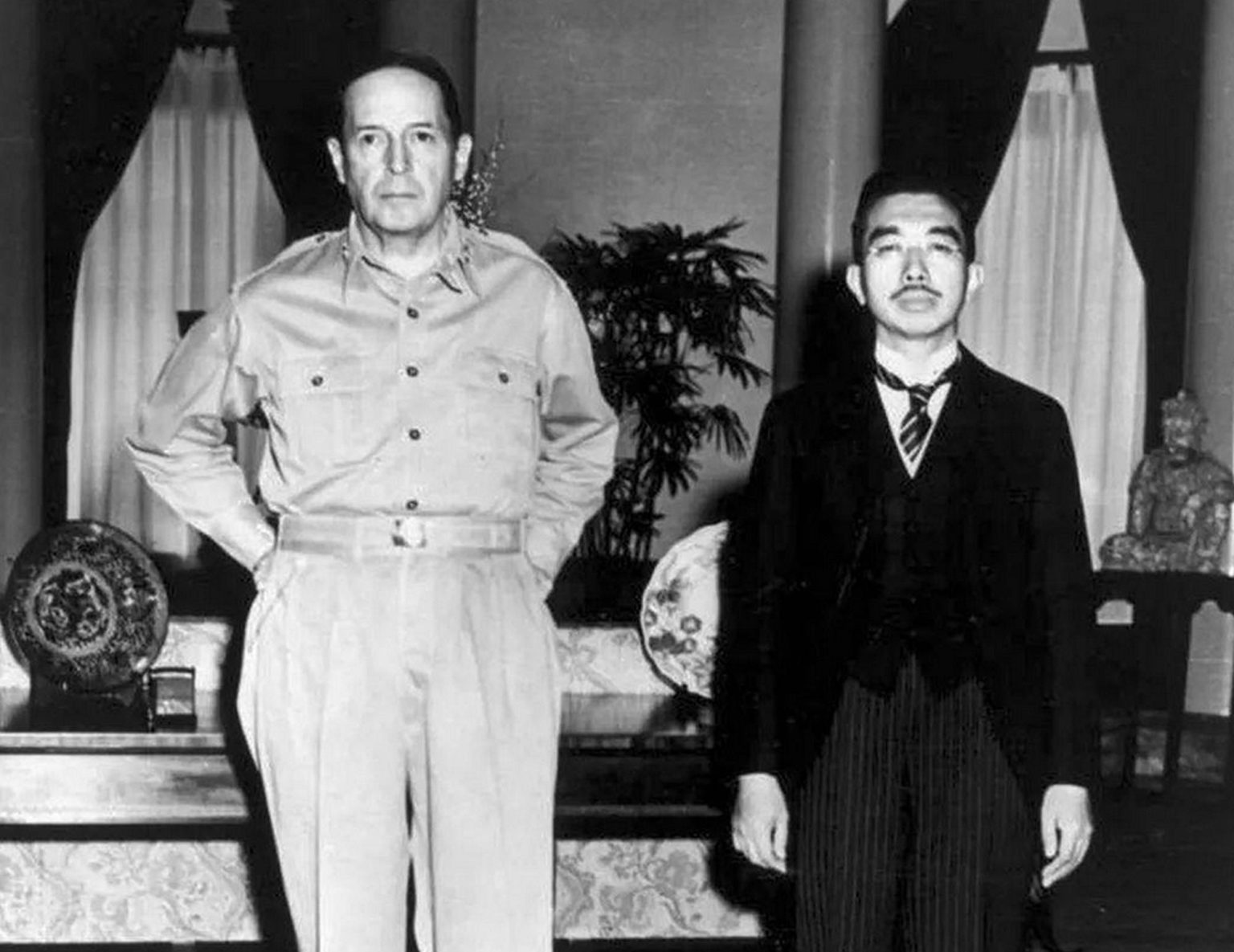

On 13 February 1946, shortly before the IMTFE convened, the supreme commander for the Allied powers, as General Douglas MacArthur was then called, shocked Japanese ministers by rejecting their draft constitution for postwar Japan and imposed America’s own draft instead. To show who was boss, MacArthur’s intermediary, General Courtney Whitney, ridiculed a Japanese aide, saying: ‘We have been enjoying your atomic sunshine.’ (1) That set the martial tone for the IMTFE, whose terms of reference were written by MacArthur.

The IMTFE convened in the auditorium of the elite Imperial Army Officers’ School, Japan’s West Point, in Ichigaya, near the centre of Tokyo. Both the physical courtroom and the list of crimes were modelled on the Nuremberg Trials.

Hideki Tojo, head of the Japanese army, and 27 other Japanese men were indicted for a trio of awful crimes familiar from Nuremberg: crimes against peace, conventional war crimes and crimes against humanity. Yet, with the exception of Tojo, whose attempted suicide in September 1945 came complete with photographs, their names are now forgotten in the West.

There were significant absences at the trial, in particular that of Japan’s emperor, Michinomiya Hirohito. Commanding Japan’s military offensives from 1937 onward, Hirohito was, as historian Herbert Bix has shown, directly involved in the planning of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor (4). But Hirohito was still revered in Japan. Washington recognised this. It realised that through Hirohito it could wield authority in Japan. Indeed, on the night that death sentences were pronounced, Hirohito dined with the trial’s American chief prosecutor.

Apart from the emperor, there were other important absences from the trial. There was no sign of Japan’s zaibatsu – the giant super-monopolies, led by Sumitomo, Mitsubishi, Yasuda and Mitsui. These had backed a series of repressive regimes before and during the war yet were excluded from the trial. Also missing was Korea, which had been ruled and brutalised by Tokyo since 1905.

Japan’s other wartime victims were also excluded – Burma, Cambodia, the Dutch East Indies, Laos, Malaya, Singapore. Still, from MacArthur’s point of view, the trial performed a service. Through its fierce attribution of war guilt, and the untouchability it conferred upon the absent emperor and the zaibatsu, MacArthur was able to set the political narrative for postwar Japan.

A new racism emerges

Like the infamous Nazi defendants at Nuremberg, the defendants at Tokyo were also judged to have misled the populace, and to have displayed a mad group loyalty to their leader. But unlike the Nuremberg defendants, those at Tokyo were not taken as symbols of a universal human evil. Instead, notes one historian, ‘as the Allied prosecutors stressed repeatedly, it was not the Japanese people who were on trial, it was their leaders – in particular, the militarists who took over the government’ (3).

There were reasons for this approach. America still wanted Japan as a stable base in Asia. Hence it was anxious to pacify the Japanese population and treat them separately from the defendants.

This was not the only difference to Nuremberg. There was also a great deal of discussion about the psychology of ‘the Japanese’. Before and during the war, the Japanese and other Asians had been conjured up in the West as sub-human, savage and bloodthirsty. But the nature of anti-Japanese racism changed during the trial. The focus was now on Japanese people’s unique racial psychology, including their supposedly immutable cultural preference for group loyalty – especially loyalty to the emperor.

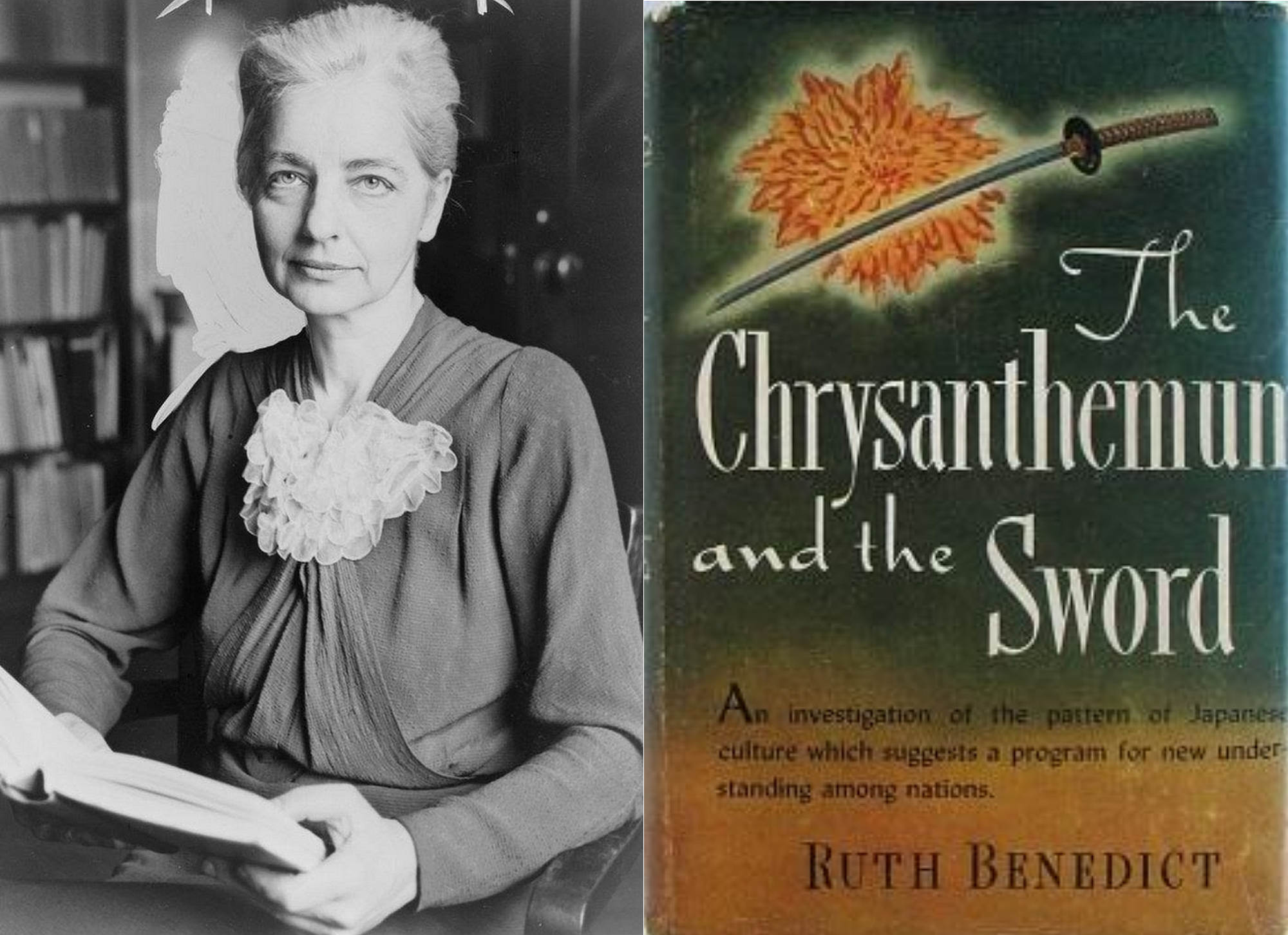

Key to this was Ruth Benedict’s The Chrysanthemum and the Sword. Published in 1946, the opening year of the Tokyo Trial, it was an instant bestseller both in America and Japan. It began life, in the spring of 1945, when Benedict, who had never been to Japan, was asked by the US Office of War Information’s foreign morale analysis division to analyse the Japanese mind. Her conclusions were based on three months of field research on behaviour among Japanese Americans in America.

Using the reports she had received from ‘capable Americans who knew Japan’, plus the rather dubious testimony of Japanese PoWs, Benedict rushed to believe that all Japanese were loyal to the emperor, adhered to group norms and hierarchy, and were more deferential to their superiors than Westerners. She was convinced, too, of ‘the primacy of shame in Japanese life’.

These stereotypes were sweeping but important. Instead of sneers about the Japanese, Benedict now offered a palatable menu of what we today know as ‘cultural difference’. By constructing a Japanese psychology in this way, Benedict helped stigmatise the Japanese masses, while exonerating the emperor. In doing so, she helped to stabilise Japan as America’s principal postwar base for Asian operations.

The court’s purpose

Crimes against peace were selected as the spearhead of the prosecution’s attack. The point was to establish Japan’s military and political leaders as responsible for war in China, and for Pearl Harbor, while obscuring the racial provocations of the US and the West, including Japan’s exclusion from the League of Nations on racial grounds.

For the purposes of the trial, the newly defined crimes under review could now, as at Nuremberg, be applied retrospectively. From the start, all the defendants were pretty much assumed to be guilty. The standard of evidence accepted was weak, and favoured the prosecution. Unlike Nuremberg, everything was solely funded by the Americans, and the prosecution solely led by Americans, even if Australia and Britain played an important role. At the discretion of the tribunal, defence counsel could be removed at any time (4). Resources for translation, stenography and other tasks were available to the prosecution, but not the defence. And the Americans determined the composition of the judges, appointing as their president Sir William Bell, who had already spent two years investigating Japanese war crimes in Papua and New Guinea (5).

At one level, then, the whole thing was constructed according to the interests of the presiding Americans. The majority judgment, in the words of Richard Minear, ‘completely ducked’ the task of defining what ‘aggression’ meant (6).

The Soviet prosecutor at the IMTFE tried to initiate a new tribunal to try personnel from Unit 731, the emperor’s fearsome chemical and biological warfare apparatus. But MacArthur ‘ensured that his initiatives were thwarted’, granting immunity to members of Unit 731 in exchange for the ‘medical data’ they had derived from their ghoulish experiments on 3,000 live human subjects in Manchuria. This is just one example of the way in which the IMTFE treated the Japanese elite selectively and with kid gloves.

Dr Kirsten Sellars, a specialist in Asia and international law, explains well the dynamic informing the trial. By focusing it on Japan’s aggression,

‘the Americans hoped to explain away the military debacle at Pearl Harbor, the Soviets wished to excuse their treaty-breaking invasion of Manchuria, and the colonial powers wanted to justify their postwar reclamation of the Asian colonies. Consequently, 36 of the 55 counts in the indictment held the accused collectively responsible for conspiring to wage aggressive wars and individually responsible for the initiation and waging of them.’

There is much in this. If, by creating NATO in 1949, the purpose of the Allies was, famously, to ‘keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down’, that of the IMTFE in 1946-8 was broadly to keep the Russians sidelined, the Americans in, the Japanese down, and the rest of Asia onside.

The importance of the Tokyo Trial today

In Asia today, both domestic politics and disputes over islands and maritime boundaries reflect the region’s bloody past conflicts. They reflect, too, the bitter, festering and imperfect settlements of the 20th century, with the IMTFE to the fore.

Until recently, the Tokyo Trial was always regarded as a junior partner to that held in Nuremberg. In recent years, however, slavish liberal devotion to globalist bodies such as the International Criminal Court, born in 2002, has revived interest in the IMTFE. And that interest will only increase further, as Japan continues to play an important, frontline role in East Asia, and its wartime deeds continue to come up for condemnation in China and South Korea.

Yes, after three decades of economic torpor, Japan does not get the attention it received in the 1980s. But Japan has a weighty past with China, a weighty military budget, and a weighty GDP. More than ever, Japan and the Tokyo Trial demand our understanding.

James Woudhuysen is visiting professor of forecasting and innovation at London South Bank University.

Main picture: Getty Images.

(1) Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Aftermath of World War II, by John Dower, Penguin, 1999, p375

(2) See Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, by Herbert P Bix, HarperCollins, 2000, chapters 11 and 12

(3) The Other Nuremberg: the Untold Story of the Tokyo War Crimes Trials, by Arnold C Brackman, Fontana/Collins edition, 1990, pp28-29

(4) ‘Nuremberg, Tokyo and the crime of aggression: an intertwined and still unfolding legacy’, by Donald M Ferencz, in The Tokyo Tribunal: Perspectives on Law, History and Memory, edited by Viviane E Dittrich, Kerstin von Lingen, Philipp Osten and Jolana Makraiova, Torkel Opsahl, Academic EPublisher, 2020, p203

(5) See With MacArthur in Japan: A Personal History of the Occupation, by Ambassador William J Sebald with Russell Brines, The Cresset Press, 1965, p156

(6) Victors’ Justice: The Tokyo War Crimes Trials, by Richard Minear, Princeton, 1971, p58

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.