‘They are like two bald men fighting over a comb’

Paul Embery on why both sides of Labour’s civil war are wrong.

The Labour Party lurches from one crisis to the next. Following its crushing defeat in the Hartlepool by-election last month, civil war has broken out once more, with Starmerite loyalists battling against Corbynite ‘radicals’. Does Labour have any hope of resolving its problems and returning to power in the near future?

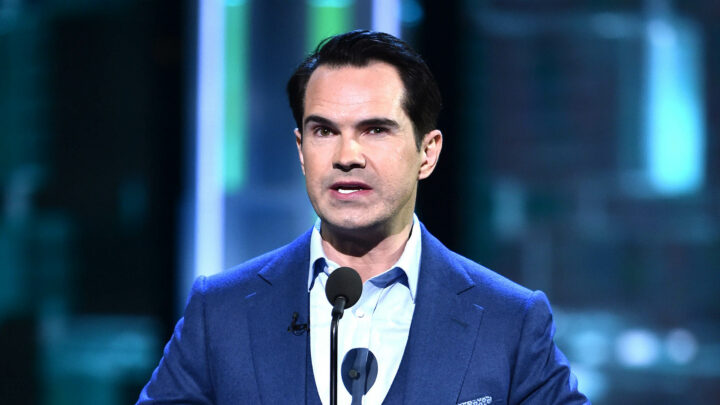

Paul Embery is a trade unionist, writer and the author of Despised: Why the Modern Left Loathes the Working Class. He joined spiked editor Brendan O’Neill for the latest episode of The Brendan O’Neill Show. What follows is an edited extract from their conversation. Listen to the full episode here.

Brendan O’Neill: You have highlighted how there is something quite phoney about the current battle tearing the Labour Party apart. At the moment, it’s the Starmerites versus the Corbynites, to put it crudely. The point you make is that those two sides have more in common than they would ever like to admit. Both of them are imbued with the same bourgeois, metropolitan, globalist worldview. What explains the intensity of the battle? Is it the narcissism of small differences? Is it that Labour is bitter because it is so far from power?

Paul Embery: Each side blames the other for Labour’s predicaments. The Corbynites and the radical left blame Blairism, and centrists and the liberal left blame Corbynism. Each side thinks that if it can reduce the influence of the other side, Labour will march to victory. Actually, these two camps are the equivalent of two bald men fighting over a comb. Neither of them realises that they themselves are the problem. And if either of them wins that civil war, they will find that the instrument that they are trying to gain control of isn’t of much use to them. Neither of them understands what needs to be done to reconnect with the country. Neither of them really understands working-class, provincial, small-town or industrial Britain. They don’t understand the communitarian impulse in those places, the desire for social solidarity and the fact that people still have traditional values.

There is an element of the party, particularly of its radical left, that isn’t willing to do what’s necessary to regain power: to make compromises, including with the electorate. All that matters to these people is that they don’t in any way dilute their purist ideology. But winning elections is about the hard business of building coalitions. Neither the radical nor liberal left of Labour points the way towards reconnecting with all of those millions of voters Labour has lost. It’s only by rediscovering the party’s working-class roots that Labour will ever stand a chance of winning power again.

O’Neill: There is an almost nihilistic element here, where Labour’s radical left seems to be driven by a desire to vindicate its past positions rather than by any idea of what might benefit Labour. These people aren’t interested in how they might reconnect with working-class voters and just have an incredibly self-serving, self-destructive approach to the party’s problems. You have written about the fact that whoever leads Labour he or she will have to face the problem of the membership. It is largely made up of young, middle-class graduates with supposedly radical views. A purge is obviously never a good thing. But there is a genuine issue here, where people are almost self-consciously holding the party back, because they are so reluctant to see it go in a direction which in any way deviates from their view of the world. What do you think is the answer to this problem?

Embery: The last thing the Labour Party needs is a purge. And the whole debate about whether Starmer should be the leader is an academic point. Whoever the leader is, they are shackled by a party that doesn’t want to go where it needs to in order to reconnect with people. Starmer deserves some credit for saying that he would get on with Brexit. He has started pressing the themes of family, community and nation, which working-class communities want to hear. But if the public doesn’t think this is authentic, if it thinks Labour doesn’t really believe in any of it, it isn’t enough. You only have to look at some of the stick that Starmer got when he made a statement in front of the Union flag – including from within Labour. It just showed that the party didn’t want to listen.

There are a handful of MPs who get it. There are some groups within the party – Blue Labour, Labour Future and the English Labour Network – which have been articulating some of the right ideas. But the danger is that, particularly on the radical left, people think that all you have to do is promise working-class communities more money and they will vote for you. It’s just not true. If it was only about economism, then Labour would have won in 2017 and 2019, when its manifesto was more economically radical than it had been for many years. Actually, people think there are things in life that are more important than money. If you don’t get that, and if you keep dismissing people as nativist bigots, they won’t vote for you. The only answer is to try to look and sound more like people in working-class communities, and to articulate some of their concerns.

O’Neill: How possible do you think it is for Labour to do that? Many wings of the contemporary Labour Party don’t understand working-class voters, their lifestyles, their ways of thinking and their approaches to the world. The working classes also feel very alienated from Labour. But it goes slightly further than that, doesn’t it? You touch on this in your book, Despised. It’s not simply that much of the modern left misunderstands working-class people, but it actively dislikes them, and looks upon them with contempt. You see this in different sections of the Labour Party, right from Emily Thornberry sneering at the St George’s flag to Corbynites’ use of horrendous terms like ‘gammon’ to describe lower-middle-class voters. You also see it in the way that much of the party views working-class people who voted for Brexit as bigots, xenophobes and racists. Doesn’t it go further than Labour being distant from the working classes, and cross the line into Labour actually loathing the people it expects to vote for it?

Embery: Undeniably, there are elements of Labour that are actively hostile to working-class communities and people who espouse traditional working-class values. They see these people as benighted and backward, and feel they have to be dragged out of their ignorance. Other parts of the left hold some public affection for working-class communities, but are privately quite contemptuous of them.

All this needs to change because Labour, for me, despite its many faults, is still the best option for working-class people to advance their own interests.

Paul Embery was speaking to Brendan O’Neill in the latest episode of The Brendan O’Neill Show. Listen to the full conversation here:

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.