‘Being a victim is not a virtue’

Susan Neiman on the reactionary roots of identity politics.

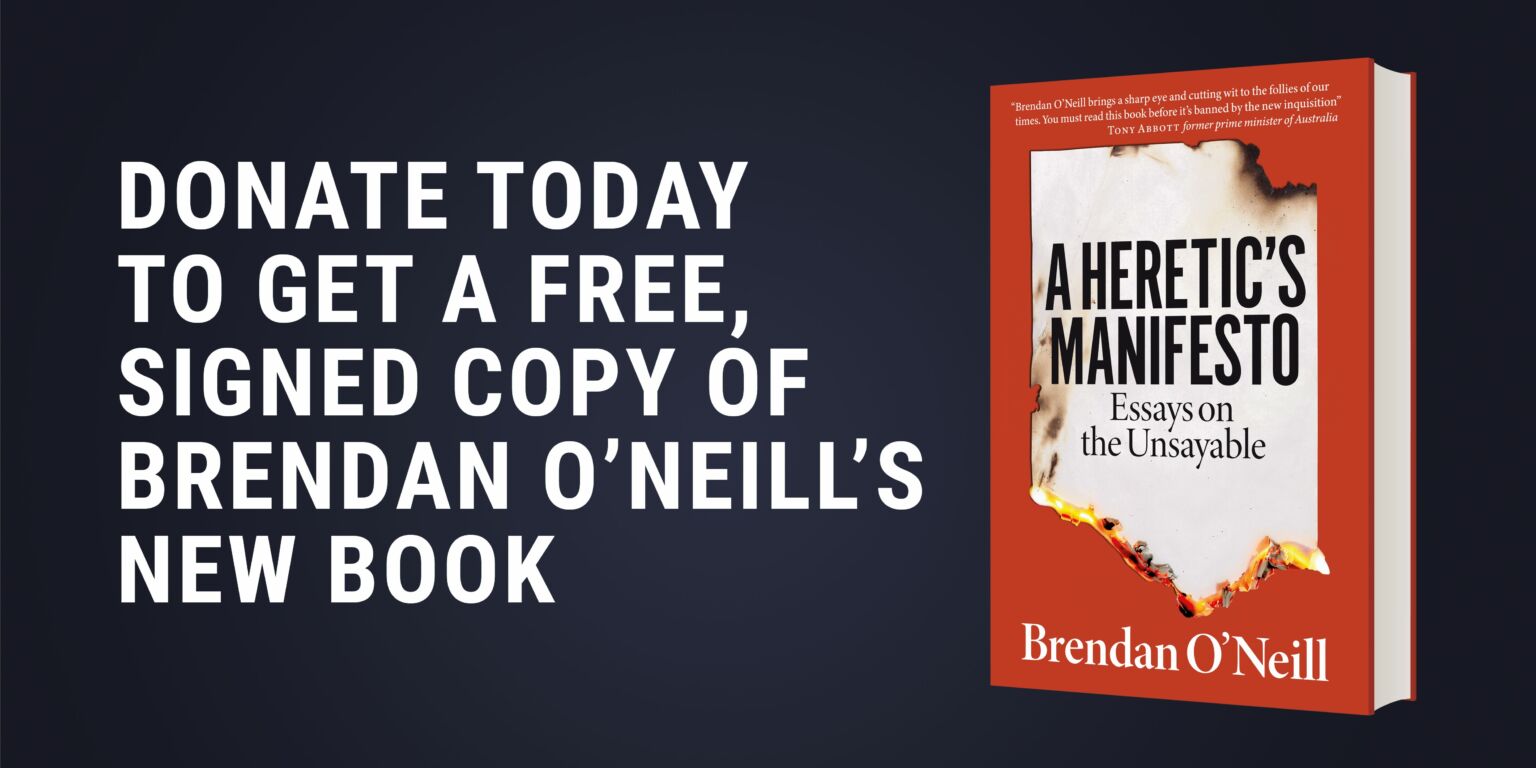

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The words ‘woke’ and ‘left’ are often treated as interchangeable. After all, many left-of-centre parties, like the Democrats in the US and Labour in the UK, have embraced woke identity politics with gusto. But, as Susan Neiman argues in her new book, Left Is Not Woke, wokeness has distorted what it means to be on the left. It has jettisoned traditional left-wing commitments to solidarity, universalism and progress, she says. Rather than setting out a path to a more egalitarian future, woke is unmistakably reactionary and authoritarian.

Susan joined Brendan O’Neill to discuss all this and more on the latest episode of The Brendan O’Neill Show. What follows is an edited extract from their conversation. Listen to the full episode here.

Brendan O’Neill: How do you define ‘woke’? What are you thinking about when you see that word?

Susan Neiman: When I first heard the word ‘woke’, I thought it was great. After all, what’s wrong with being awake to social injustice and trying to do something about it? It is certainly a movement that appeals to ideals that were traditional to the left. It speaks to concern for people who are marginalised, a determination to root out injustice, and a desire to correct or at least to acknowledge historical injustices. Yet much of what passes for woke thinking is fueled by theoretical assumptions that are actually quite reactionary and were never part of the traditional left at all.

Mainstream media have thoughtlessly bought into many of these woke assumptions, such as the idea that people are fundamentally determined by what tribe they were born into. You see that sentiment repeated in the New York Times and the Guardian. Yet this idea is anathema to what it has always meant to be on the left. It was traditionally a very right-wing view that you can only deeply connect with somebody from your tribe and you therefore only have real obligations to people within your tribe. Whereas the left-wing standpoint was that your tribe can encompass the whole world and it is not a determining identity. Of course, we’re all affected by the culture we grew up in and the histories of our ancestors, but they don’t determine us. That’s one way woke has diverged from the left.

Another way is its despair or cynicism about the possibility of making progress. It’s certainly true that there are woke activists who want to make progress. But the majority of them don’t actually acknowledge that progress has been made. They believe that we’re just as racist as we were 50 or 100 years ago, or that the patriarchy has ruined women’s lives forever. Any improvement is basically dismissed as a sham. If you really believe that, then you’re not going to believe that human beings working together can actually make progress.

Many of us spend time over coffee, over beer, late at night, telling stories about one instance of woke excess or another. But it doesn’t seem fruitful to me. It is much more important right now to understand the ideas fueling that excess.

O’Neill: The victim has become the chief political player in the 21st century. How important and problematic do you think the valorisation of the victim is in this kind of politics?

Neiman: The valorisation of the victim is not something that the woke invented – it’s something that has changed throughout history. Typically, history has been written by the victors, which means that we’ve mainly had a heroic account of history. By and large, the victims were forgotten. Sometime around the middle of the 20th century, that changed. Of course, initially it was an act of justice. Let us hear the victims’ stories. Let us not forget that they were there, even if they couldn’t be saved. Let us care for them, if possible. All of that seems like a great idea, along with deconstructing certain traditional military notions of heroism. However, we have now reached the point where victimhood itself is fundamental to people’s identity.

I’m not suggesting that we go back to erasing victims. What I am suggesting is that we go back to the point at which caring for the victim is a virtue. We should take care of victims and see if we can redress the wrongs that they’ve suffered. But being a victim itself is not a source of virtue at all. It’s just something that happens to you or something you’re born with.

I think it’s extremely disturbing. It changes our sense of ourselves. We see all these cases of people straining to find a victim identification or, in some cases, even faking a victim identification. I’m not saying that people’s suffering should never be addressed, but spending too much time thinking about your own victimhood is not good for the soul. And it’s not good for whatever sense of common ground we might want to share or build. There ends up being a kind of victimhood competition, which splits or undermines groups. Defining yourself according to the worst things that ever happened to you is not the way to go.

Susan Neiman was talking to Brendan O’Neill on The Brendan O’Neill Show. Listen to the full conversation here:

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.