Long-read

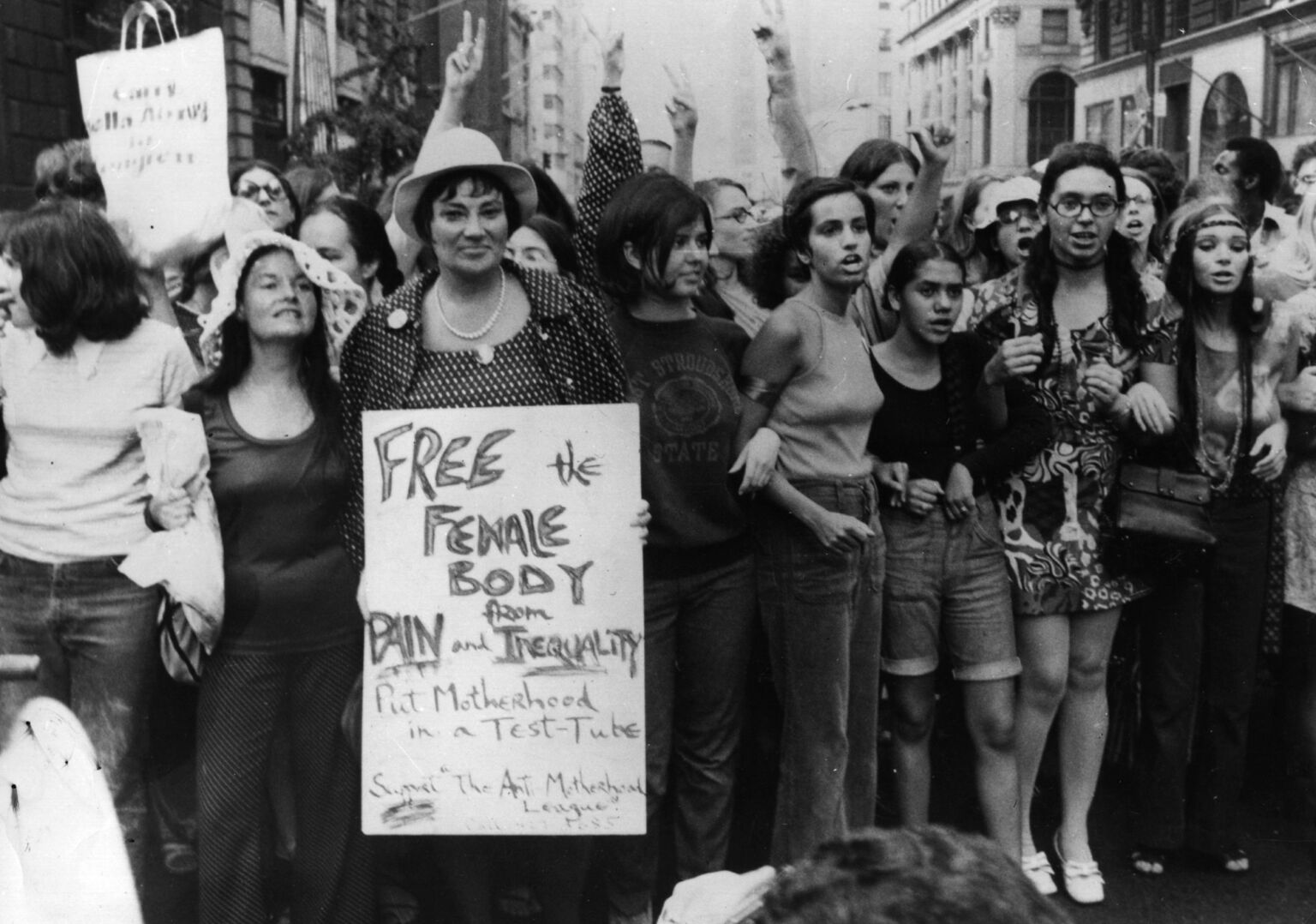

The reactionary turn against the sexual revolution

Women’s freedom is not to blame for today’s crisis of intimacy.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

‘Those of us who came to adulthood post-Pill stand on another shore, an ocean apart from all generations before us.’ That’s how Baroness Alison Wolf describes the impact of the invention of the contraceptive pill on the lives of women in The XX Factor. ‘Sex can be safe. You can relax about it. Women can avoid an undesired pregnancy, completely, securely, and on their own’, she writes.

Chrissie Hynde, lead singer of the Pretenders, could hardly be more different from the scholarly Professor Wolf. Yet, born just two years later in 1951, she shares Wolf’s view that the Pill revolutionised women’s lives. ‘In the name of women’s lib, women were becoming like men, and that was good news for me because I wanted what the boys had’, Hynde wrote in her 2015 memoir, Reckless. ‘In thinking we were in charge of our own sexuality, now we could say “yes” instead of “no”.’

Hynde would later go on to question whether having sex ‘like men’ was really desirable for women. But what’s clear is that, for both Wolf and Hynde, the promise of the sexual revolution was about far more than consequence-free sex. Liberated from worrying about unwanted pregnancies, it became possible for women to imagine having what the boys had not just in the bedroom, but also in the office, the lecture theatre and the recording studio. In the decades that followed the development of the Pill, women’s lives changed forever.

Today, as the Pill enters its seventh decade, self-described reactionary feminists, such as Mary Harrington and Louise Perry, want to turn back the clock on the sexual revolution. They argue that both hormonal contraception and the social freedoms permitted by consequence-free sex are bad for women. Harrington longs for women ‘un-neutered by progesterone’ to be at the forefront of a new era where people ‘take more of a realist stance on where the limits to individual freedom really are’.

In critiquing the sex part of the sexual revolution, the arguments of today’s reactionary feminists have a long history. At the very moment sex stopped being about procreation, it began to be seen, by some feminists, as a form of oppression and a means of patriarchal domination. Writing in 1970, feminist author Kate Millett described intercourse as ‘an assertion of mastery’, one in which man asserts ‘his own higher caste and proves it upon a victim who is expected to surrender, serve and be satisfied’. Later, radical feminist Andrea Dworkin bluntly described ‘the role of the fuck in controlling women’. In her 1987 book, Intercourse, Dworkin elaborated her theory that heterosexual sex is used by men to control, possess and dominate women.

At that time, Dworkin was writing at the height of the AIDS epidemic. Panic-fuelled campaigns drew a link between casual sex and the transmission of AIDS. Author Katie Roiphe, in The Morning After: Fear, Sex and Feminism, her exploration of attitudes to sex on campus in the early 1990s, described how ‘instead of liberation and libido, the emphasis [was] on trauma and disease’. For young women at this time, she explained, ‘the shift from free love to safe sex is itself part of our experience’. Roiphe argued that ‘our sexual climate, then, incorporates the movement from one set of sexual mores to another’. This moral shift was hastened by the agreement between radical feminists and social conservatives that ‘free love’ had gone too far.

Today, sexual mores are shifting again. Harrington writes about wanting to ‘re-wild’ sex, to make it less ‘safe’. She doesn’t want couples to risk diseases, but pregnancy. ‘Rejecting birth control is the first and most radical step women can take, in healing the disconnect between us and our own bodies’, she writes. ‘In a lifelong partnership, the possibility of conception can itself be deeply erotic.’ There clearly is no accounting for taste when it comes to sexual predilections. Far from being aroused, the overwhelming majority of women I know are terrified by the life-changing consequences of an unplanned, unwanted pregnancy.

In seeking to reverse the sexual revolution, and making casual but ‘safe’ sex taboo, reactionary feminists want intercourse returned to long-term relationships and, ideally, marriage. Perry advises young women to ‘hold off on having sex with a new boyfriend for at least a few months’, and ‘only have sex with a man if you think he would make a good father to your children’. Turning back the clock on the sexual revolution to this extent requires a full-on return to 1950s morality. The reactionary feminists rehabilitate sexist assumptions that men are always up for it while women put out only under duress. They assume that women, once pregnant, will delight in the opportunity to retreat from the public sphere of work, politics and pubs and into the private sphere of the home. They assume that women are best served by chastity pre-marriage followed by domesticity in wedlock.

Such arguments are not simply quaint; they redefine what it means to be a woman today. In removing the risk of pregnancy, the Pill – and, crucially, access to abortion – liberated women to enjoy sex and pursue a life beyond baby-making. For middle-class women, this meant fun, travel and careers. For working-class women, it meant financial independence, the ability to leave an abusive relationship and a way to avoid the physical toll of repeated pregnancies and housework. These are not trivial gains. Yet arguments against the sexual revolution have gained traction in recent years. Why?

The turn against the sexual revolution

A decade ago, it was popular for feminists to argue that women were not just equal but also fundamentally the same as men. Cordelia Fine wrote in Delusions of Gender that there are no ‘blue brains’ or ‘pink brains’. Instead, she argued that differences between men and women are a result of our different socialisation. Giving girls dolls and boys trucks to play with means that, as adults, women exhibit ‘feminine’ traits while men behave in a more ‘masculine’ way. This argument is compelling because it suggests that changing the way we socialise children – effectively neutralising gendered traits – can bring about equality. Unfortunately, as no child has yet been raised in a laboratory, the exact relationship between nature and nurture is difficult to ascertain. More importantly, it is often through gendered socialisation that people take their place in the world, even if, ultimately, they go on to reject such assumptions.

The ‘not just equal but the same’ argument contributed to the belief that sex differences are socially constructed and can be educated out of people with gender-neutral clothes, toys and schooling. It also contributed to the view that sexed bodies are inconvenient containers for our mind-based gender identity, rather than a fundamental part of who we are. By having some bits chopped off or other parts added on, the argument goes, we can align our bodies with our minds and be our true (trans)gender selves. The terrible consequences of such beliefs are evident in the medicalisation of so-called trans children and the erosion of women’s rights in the name of gender ideology. Even the seemingly more benign promotion of gender neutrality speaks to a moral reluctance to socialise the next generation of young people into existing social norms. It is important to challenge such anti-family and anti-human views.

At the same time, today’s reactionary feminists are also responding to a crisis of intimacy. Statistics show us that people today are less likely to marry and less likely to have children than they were 50 years ago. Those who do get married do so later in life, have fewer children and are more likely to get divorced. Pornography is not just readily available, it also leaks into a more sexualised climate overall. Hook-up culture and dating apps promote sex on demand and without emotional attachment.

But, at the same time, other data suggest young people postpone first sexual encounters and have less sex than older generations. It seems that while the original promise of sex freed from pregnancy was fun and a source of fulfilment, today’s permissiveness offers neither of these things. Instead, panic about sexually transmitted infections now sits alongside more overwhelming fears about ‘catching feelings’ or ‘misreading signals’ that might lead to unwanted sex or false allegations of misconduct.

Today’s reactionary feminists are right to be concerned about all of these trends. But to challenge the widespread disenchantment with sex, the degradation of relationships and the family, and our moral reluctance to socialise children in our own image, we need to understand the causes of the problems we face. By singling out the Pill and pinning blame for our current problems on the sexual revolution, Harrington, Perry and their socially conservative followers risk overlooking the far bigger social, political and cultural problems we face. Worse, in seeking to overturn the gains of the women’s liberation movement, they risk making life worse for millions of women.

The dominance of transgender ideology in our schools and institutions is no more a result of surgical advances than hook-up culture is a product of the Pill. Joining dots between contraception, casual sex and a crisis of intimacy is seductive precisely because it is simplistic. It ignores broader trends such as the increasing atomisation and the collapse of solidarity that has beset society. Hook-up culture does not create this atomisation, it reflects it. Likewise, the avoidance of intimacy is a symptom – not a cause – of a more fundamental lack of connection between people.

Once, solidarity meant a deep-rooted sense of having something in common with other people, of having shared values and a shared stake in the future, premised on community, social class or the biological reality of womanhood. By contrast, today’s phoney identity groups focus on what divides people rather than on what unites them. Strangers become potential threats to our physical safety and mental wellbeing, rather than fellow humans. In this context, sex does not build intimacy or solidify relationships, but instead poses emotional risks. Eroticising the possibility of pregnancy will not change this. Instead, it is likely to amplify people’s sense of the risks of sex still further.

Reactionary feminists tend to blame this erosion of solidarity on an excess of freedom. ‘It’s not just women who need a freedom haircut; it’s everyone’, says Harrington. Again, freedom can only be so readily denigrated when it is poorly understood: when it is reduced to a consumer choice between one brand or another; or a personal lifestyle choice to go vegan or raise gender-neutral children; or simply the freedom to alter our own bodies, perhaps by getting a tattoo or a piercing or something more drastic. Seen as such, freedom appears trivial.

Worse still, when freedom is reduced to a lifestyle choice, it is seen as a means of avoiding responsibility. And so a woman’s freedom to work is judged to be in opposition to her responsibility to her children. This misses an older, deeper sense of freedom as something that emerges from our responsibility to others – whether to our families or our communities. Freedom and solidarity go hand in hand. That is what makes it so precious. Far from having an excess of freedom, our lives are blighted by the lack of it.

In order to express solidarity with others and exercise freedom to the full extent, we need to see other people as autonomous, capable and rational beings. Today’s reactionary feminists do not see people in this way. Perry’s case against the sexual revolution hinges upon the inability of women to consent to casual sex in almost all circumstances, including when they might say ‘Yes!’. Arguments about women’s false consciousness in the face of persuasive men and permissive cultural trends have a long history. But until feminists come to accept that, as adults, other women are able to consent to things that such feminists might personally find distasteful, and that women can and should take personal responsibility for their actions, they do nobody any favours. Deprived of agency, women are reduced to the status of children, rendered defenceless in the face of men, dating apps, adverts or pop videos. If women are seen as vulnerable creatures, unsure of their own minds, swayed by their instincts and hormones, easily manipulated by social pressures and unable to consent to sex, then it is easy to see why reactionary feminists deem them to be incapable of handling freedom.

Reactionary feminists identify some genuine problems we face today: disregard for the family, the crisis of intimacy, the cheapening of freedom, the notion that gender identity trumps women’s sex-based rights. But none of these things has been caused by the Pill. And none of them will be resolved by turning back the clock on the gains of the sexual revolution. For many women, life before the Pill was not blissful domesticity in the security of a loving relationship. It was financial dependency, physical drudgery and mind-numbing boredom. The fight for women’s liberation was not about abandoning children or relationships; it was about women’s freedom to enter the world and to join with others in making it a better place for everyone. We reverse these gains at our peril.

Joanna Williams is a spiked columnist and author of How Woke Won, which you can order here.

Pictures by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.