Long-read

The myth of the ‘nasty Noughties’

The Russell Brand allegations have sparked an absurd rewriting of history.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

In the aftermath of the allegations of rape and sexual assault levelled against Russell Brand, the mainstream media have advanced the same identikit argument. Brand’s alleged wrongdoing, they chorus, was ‘enabled’ by the popular culture of the 2000s. This era has now even been rechristened the ‘nasty Noughties’.

The conformity of the response has been striking. You’d think at least some among our cultural elites might hesitate before effectively using the alleged crimes of one man, credible as they seem, to damn an entire era. Yet from the BBC to the Telegraph to The Times to the Guardian, the same summary judgement has been issued. Everyone who consumed and contributed to the culture of that era, from reality TV to the pre-Leveson tabloids, is guilty of aiding and abetting Brand in anything he may or may not have done. In the words of the Guardian’s media editor, we were ‘complicit in his rise’ and, sotto voce, his alleged crimes.

This bout of era-blaming, writ large in the endless ‘I hate the 2000s’ op-eds generated since Dispatches and The Sunday Times broke the Brand allegations, rests on a nightmarish re-imagining of Noughties culture. It is now being actively conjured up as a time in which misogyny was rampant, cruelty quotidian and compassion absent. ‘Ironic, nihilist, hypersadist’, as one writer now characterises it.

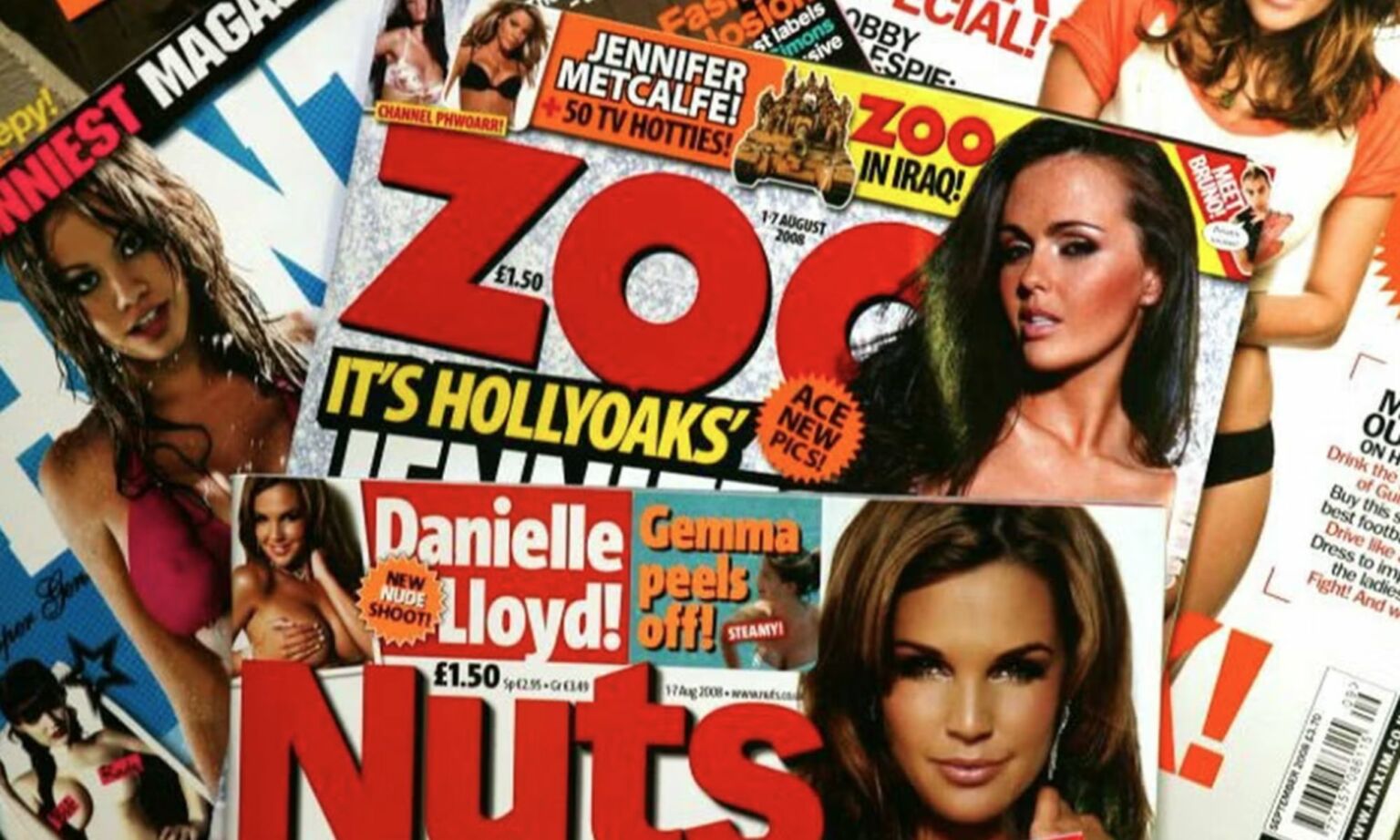

A Telegraph columnist calls the Noughties ‘a cesspit in the UK’. Apparently, it was an era of ‘grubby’ lads’ mags that were tantamount to soft porn’, with ‘tabloid celebrities such as Jordan consuming acres of column inches’. And all this, he sniffs, led to the ‘widespread acceptance of Brand’, the very embodiment of ‘toxic masculinity’. According to one Evening Standard columnist, ‘we nourished a culture of leaked sex tapes and upskirt pictures of female celebrities “falling out” of nightclubs, a world where women were asked to laugh along with rape jokes but still branded as sluts for having casual sex at all’. The New Statesman portrays turn-of-the-century Britain as the land of ‘Big Brother – with its voyeurism and public indecency – and Little Britain – with its blackface and ethical squalor’, and casts Brand ‘as the spiritual leader of the nihilism that gripped TV, and the wider culture’. Even The Economist took time out from globalist boosterism to claim that Brand was ‘the personification of a cruel, misogynistic and politically vacant age’.

The retro-dystopianism has been relentless. One thirtysomething Guardian columnist recalls ‘boys with their penises out in the classroom… pornographic university hazing rituals’ and a ‘pervasive rape and raunch culture that it felt impossible to speak out against’. And in a much longer Guardian piece, another columnist conjures the Noughties up as an era of ‘sadistic tabloid misogyny’. She dredges up as evidence the Sun’s reporting of an online countdown to the 16th birthday of one-time child chorister Charlotte Church; and an occasion in 2008, when ‘photographers lay on the pavement’, outside the venue where Harry Potter actress Emma Watson was celebrating her 18th birthday, ‘to take pictures up her skirt that it would have been illegal to print 24 hours before’.

This then was 2000s Britain, as remembered by our cultural elites. A laddish Last Days of Rome, with Russell Brand cast as its dissolute emperor. A decadent cultural empire in which males flashed without compunction, the redtops gleefully counted down to a child singer reaching the age of consent, and paparazzi tried to grab shots of a young actress’s private parts. The allegations against Brand, commentators chime as one, are utterly and depressingly unsurprising. In the Sodom and Gomorrah of Noughties Britain, such behaviour was permitted, licensed, perhaps even encouraged. One Atlantic staff writer, noting ‘the open predation that was everywhere in popular culture then’ was moved to ask ‘how Millennial women in Britain survived the aughts’.

It’s a question anyone might ask right now, given the grim image of the Noughties currently being projected from across the media. But Millennials of both sexes did ‘survive’ the Noughties for one simple reason. It really wasn’t the misogynist hellscape that today’s revisionist hype-merchants describe.

Indeed, some of the specific claims made about the Noughties in the aftermath of the Brand allegations are simply distortions. Take the clock counting down to Charlotte Church’s 16th birthday, which several commentators have cited as proof of the creepy misogyny of the era. There was indeed such a clock, hosted on an obscure, anonymous website, but few knew about it in 2002. The existence of this creepy clock was only really drawn to public attention in 2011, after Church told the Leveson Inquiry into press standards of her anger at said clock featuring on the Sun’s website in 2002. But she had misremembered. Neither the Sun nor any other tabloid had put the clock on their websites. At the time, the tabloids and the wider press, including the BBC, had merely reported on Church’s management’s angry response to this creepy website. And these reports were hardly approving. The Mirror led with quotes from one Church fan who said, ‘It’s nasty. She’s still a schoolgirl.’ Yet, incredibly, these few, far-from-salacious news reports from 2002 are now being re-imagined as something much more sinister.

Then there is the claim that in 2008, ‘photographers lay on the pavement’ in order to take upskirt pictures of Emma Watson on her 18th birthday. Watson has talked of this incident a lot in recent years, and it sounds repellant. But according to Watson in 2009, when she first relayed this story to an outraged Mail on Sunday, it was just one photographer who, trying to outdo his colleagues, decided to lay on the floor. And he was labelled as ‘sick’ in the reporting.

The Mail’s judgement shouldn’t surprise us. The tabloids of the Noughties were not actually encouraging men to lust after young or underage girls. Quite the opposite. They were obsessed with tackling paedophiles, even being accused by the ‘respectable’ press at the time of fostering a paedophile panic. This reached its height with the News of the World-led campaign for a so-called Sarah’s Law, named after eight-year-old Sarah Payne who was murdered by a convicted sex offender in 2000. The government of the time eventually adopted Sarah’s Law in the shape of the child-sex-offender disclosure scheme, which gives the public access to information on the whereabouts of people on the sex offenders’ register. Whatever else you might think of the tabloids of the 2000s, they hardly encouraged ‘open predation’.

Of course, anyone could misremember or exaggerate the significance of particular incidents from 15 or 20 years ago. Just as anyone could carelessly overstate the influence of lads’ mags, despite their circulation being in steep, terminal decline from 2005 onwards. But what we’ve seen since the Brand allegations broke is not a case of the old memory playing tricks. It’s a concerted and wilful attempt to misrepresent or, more accurately, demonise the culture and society of an entire era. Anything that cuts against this image of the nasty Noughties has been written out.

There’s no mention in any of the myriad nasty-Noughties hot takes of just how bland much of that era’s cultural output was. It was Coldplay, The One Show and endless Richard Curtis films just as much as it was Loaded, Nuts and Rebecca Loos masturbating a pig on Channel 5.

As left-wing theorist Mark Fisher argued in Capitalist Realism (2009), the 2000s were marked largely by cultural exhaustion and the impossibility of innovation. Pop music endlessly echoed older versions of itself, from revivals of new wave and garage rock to endlessly reissued blokish britpop. And remakes, sequels and prequels took over the multiplex. Any popular modernist impulse in music, TV and film seemed to have given way to retreading and reiterating past forms – a reflection, Fisher argued, of the broader political exhaustion of the post-Cold War era. It was less a moment dominated by taboo-breaking nastiness, than by bland, safe retro-philia, and a sense of low-level, increasingly medicalised angst.

There’s no mention either from today’s anti-Noughties commentators of just how illiberal, how hyper-regulated, that period of time was. This was the era of New Labour, a political project noted precisely for its illiberalism. The Blair government may have left the economy to its own devices, having given the Bank of England control over monetary policy in 1997, but it intervened with increasing zeal into civil society. Personal life became the central object of policymaking. The private realm became a public matter. Our consumption habits were regulated, our speech curtailed, our sex lives politicised. Even those who appeared to violate such strictures, like the Libertines’ Pete Doherty or indeed Russell Brand, presented their debauchery in terms of various addictions and forms of mental-health speak. They were patients of the state rather than bohemians.

This was not a licentious, anything-goes era, in which men were free to terrorise women under the cloak of laddish banter. Far from it. It was an era in which freedom itself was treated as a problem. From the perspective of the British state, citizens, especially working-class ones, couldn’t be trusted with their own liberty. Like ASBOs, the smoking ban, laws against offensive speech and a whole raft of further legislation eroded individual autonomy, and ate ever further into the private sphere.

The popular culture of the Noughties was deeply entwined with this growing political illiberalism. And nowhere more so, perhaps, than comedy. The best of it played on the increasingly stultifying nature of regulated social life in Noughties Britain, on the cloying political correctness of the era, on the politically fuelled need to be saying and doing the right things. The Office (2001-03) and Peep Show (2003-15) remain sublime comedies of right-on manners. And there was much in the British comedy of the era that was thumbing its nose at New Labour’s paternalism – and the rise of the so-called nanny state – by being wilfully puerile, deliberately offensive. It was an infantile, willy-waving reaction to an infantilising political culture. To those saying ‘You can’t say that’, the likes of Frankie Boyle or Little Britain effectively said, ‘You just watch me’. As Matt Lipsey, the director of the second series of Little Britain, said of the show recently: ‘It was seen as pushing the boundaries. [David Walliams and Matt Lucas] were on a high, basically recognising that audiences were responding. That was a signal to say, “How far can we go?”’ Breast-feeding men-children and crap transvestites was the answer.

Which brings us to Russell Brand himself. His comedic schtick, honed as the anarchic, super-charged presenter of assorted Big Brother spin-offs in the mid-2000s, was very much of this cloying, infantilising moment. He would regale his growing TV audiences with knowingly pretentious smut, a verbose interlacing of high-culture references with talk of his ‘ball bags’, ‘dinkle’ and a whole lot of wanking. He was a cross between the London Review of Books and Roy Chubby Brown, a precocious schoolboy show-off, mocking the decorum of the Noughties classroom. That was the source of his appeal, such as it was. Not some rampant misogyny rooted deep in British society and unleashed during this supposedly evil decade. But obscene silliness and a large vocab.

Yet the reality of this very recent historical moment is now being revised out of existence. Aspects of the era which contradict the narrative of unfolding, ‘hypersadist’ cruelty and rampant predatory misogyny are being sanded away. Removed from view. Hidden from plain sight. We’re witnessing a rich, multi-layered period of recent social history being forcibly reconstructed as the Bad Old Days.

This shouldn’t surprise us. A shallow, moralising presentism has prevailed among our cultural elites for many years now. Large swathes of complex social, political and intellectual history are increasingly damned in terms of some present-day identity politics. The Enlightenment is now re-imagined as little more than a Eurocentric, colonialist power-play. The foundation of the United States is now reduced to an act of systemic racism. And yesterday’s heroes are now cast as today’s villains, their statues toppled, their books revised, removed or stamped with a trigger warning.

Still, this presentist assault on the Noughties is remarkable for the chronological proximity of its target. It’s one thing damning Winston Churchill as a racist, or calling George Orwell a sexist. They at least are safely dead. But all those now damning the era of Big Brother and the Inbetweeners lived through it themselves. Their targets are almost all alive and well. No wonder one columnist admitted suffering ‘moral whiplash’, such is the speed at which the hitherto acceptable is being rendered ‘inappropriate’. By condemning the 2000s, they are effectively now drawing the line between the virtuous present and the wicked past in our own time. This hyper-presentism has been picking up steam for a few years. Hence, the endless stream of writers and performers regularly feeling the need to say something along the lines of ‘it wouldn’t be made today’ of a TV show made five minutes ago. But the Brand allegations have brought it all to a head.

What we are witnessing is a form of manic, crusading presentism. A form of moralising propaganda. An attempt to morally affirm elite ideology by re-casting even the very recent past as a site of evil behaviour and attitudes. Indeed, what’s striking about many of the pieces written in response to the Brand allegations is how explicitly the ‘nasty Noughties’ are being marshalled to legitimise the elite crusades of the present. Some writers have used the allegations to continue their war on the tabloids and to justify the restrictions on press freedom after the phone-hacking scandal. Others have used them to legitimise #MeToo and the ongoing campaign against so-called everyday sexism. And almost all have used the Brand scandal to justify cancel culture more broadly.

So, noting what is now seen as the bad behaviour of the Noughties, one columnist argues that had social media been around in the mid-2000s, ‘a bit of a Twitterstorm might have done the trick’ to clean things up. Another argues that those nostalgic for the relative freedom of the 2000s – ‘When a joke was just a joke… and a shagger was a tabloid hero’ – are merely struggling to cope with ‘cancel culture’, which he defines as a ‘new world of consequences’. The Economist, which usually likes to pose as a liberal magazine, even praised the ‘censorious and sometimes puritanical attitudes that are prominent today’ as a necessary reaction to ‘the excesses of a previous era’.

That is the function the Bad Old Days of just a few years ago are now playing. That is why so many among our cultural elites have, almost as one, turned on the 2000s. Their demonisation of that era provides the fuel for the elite crusades of today. Their retrospective cancellation is being used to power current cancel culture.

Perhaps worst of all, condemning the broader Noughties culture in this way cannot help but strip potential perpetrators of responsibility. It treats the horrendous things Russell Brand is alleged to have done as inevitable, as almost to be expected. If rape and sexual assault were really ‘enabled’ and encouraged by the 2000s, then how can any one person be held culpable? This rapid rewriting of the past leads to some truly grotesque conclusions.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.