Long-read

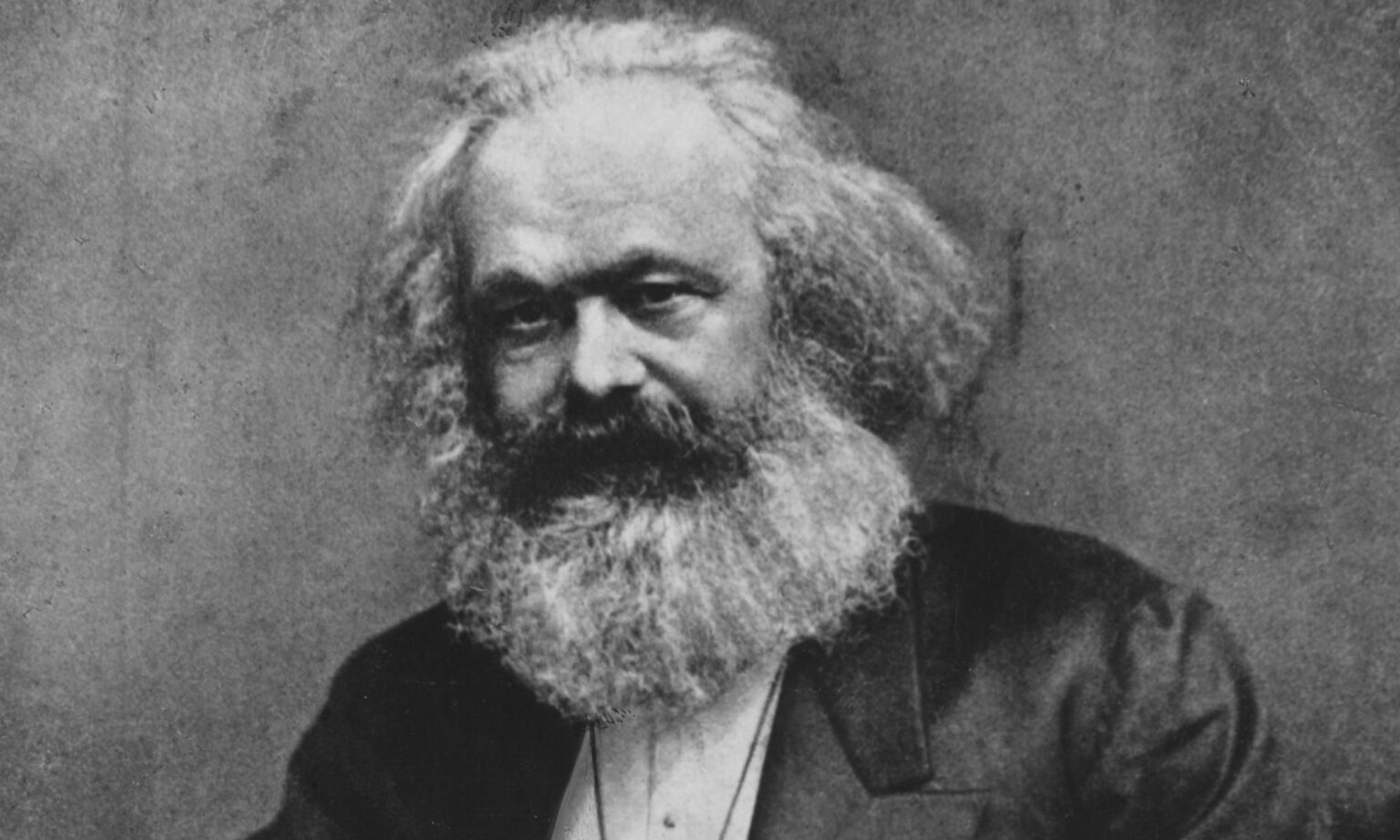

The myth of a ‘green’ Karl Marx

There is no trace of ‘degrowth communism’ in the great radical’s work.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Since the mid-2010s, there has been a surge in articles and books supporting the idea of degrowth – a leftish environmentalist, economic argument against ‘growth-obsessed’ capitalism. Its advocates claim that the current capitalistic system is ‘geared towards collapse’ (1).

Degrowth theorists often talk in apocalyptic terms. In his bestselling degrowth text, Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism (2023), Kohei Saito anticipates the ‘end of human history’. An associate professor of philosophy at the University of Tokyo, Saito argues that democracy, capitalism and ecological systems have together fallen into ‘chronic crisis’. To avert disaster, he calls for a stationary, ecologically benign communist society.

In many ways, degrowthers are attacking more than just economic growth. As Matthias Schmelzer et al put it in The Future is Degrowth (2022), ‘we must analyse how the modern growth paradigm builds on and is interlinked with growth as a social and material process, going back at least to colonisation and early capitalism’ (2). In targeting the ‘modern growth paradigm’, these thinkers reveal the true nature of their project. The calls for degrowth represent a rejection of modernity in its totality.

It’s in this vein that degrowthers attack the Enlightenment, and its elevation of ‘scientific reason’ in particular. They claim that faith in human reason lies at the root of man’s fatal domination of nature, which they see as the ‘destructive side of the Enlightenment and modernity’ (3). Degrowthism is therefore best seen as a further manifestation of Western elites’ disenchantment with modern civilisation, from the European Enlightenment onwards.

The growth of degrowthism

The use of the term ‘degrowth’ draws specifically upon the cultural distaste for economic growth that began to prevail since the 1970s. During the West’s postwar boom, capitalism largely justified itself through its ability to generate wealth – the ‘new ideology of growth’, as Andrew Gamble puts it. But as Western economies entered what was to become a long depression during the 1970s, the ideology of growth came under attack. Fred Hirsch in The Social Limits to Growth (1977) claimed that the ‘process of growth itself created the tensions which destroyed it’.

The political left in particular started to warm to the idea of degrowth during the 1970s and 1980s. The left had traditionally argued for economic growth because it raised workers’ living standards. But now left-wingers were blaming growth for the problems of capitalism, such as income inequality. Left-wing criticism of capitalism was mutating into what Daniel Ben-Ami was to call ‘growth scepticism’.

So-called radical critics were now focussing on growth, rather than the capitalist system. They condemned corporate greed, over-consumption, and environmental damage as the dire consequences of the pursuit of growth. Out of this milieu, the degrowth movement emerged. Indeed, many advocates of degrowth see themselves as radical anti-capitalists. They openly argue that putting an end to growth would point to a world ‘beyond capitalism’.

Turning Marx into a degrowth communist

Such is the depth of support for degrowth on the left, that some self-described Marxists even claim that Karl Marx himself was actually an environmentalist and early advocate of degrowth.

Paul Burkett and John Bellamy Foster, two leading writers for the long-established American socialist magazine, Monthly Review, are usually credited with ‘rediscovering’ Marx’s ecological critique of capitalism – Burkett in Marx and Nature: A Red and Green Perspective (1999) and Foster in Marx’s Ecology: Materialism and Nature (2000).

With the influential Marx in the Anthropocene (2023), Kohei Saito has gone even further. He claims that not only was Marx an ‘ecologically conscious person in the modern sense’ (4), he was also a ‘degrowth communist’ – that is, he was an advocate of ‘a variant of ecosocialism [that] aims for a post-scarcity society without economic growth’ (5). Saito argues that Marx was concerned by the problem of sustainability and ‘repeatedly warned that the capitalist development of productive forces undermines and even destroys the universal metabolism of nature’ (6).

Saito’s claims for Marx being a proto-environmentalist stem from a reading of Marx’s post-1868 notebooks on the natural sciences. It is there, claims Saito, that Marx developed a new ecological vision of post-capitalism before his death in 1883. In Saito’s view, Marx went beyond eco-socialism and ‘ultimately became a degrowth communist’ (7).

In an interview with the Guardian in 2022, Saito said that these notebooks show that ‘Marx was interested in sustainability and how non-capitalist and pre-capitalist societies are sustainable, because… they are not growth-driven’. This is an odd, ahistorical claim. The term ‘sustainability’ only developed a specific environmentalist meaning from the 1980s onwards, especially after the publication of the UN Commission on Environment and Development’s Our Common Future in 1987.

Saito goes even further by concluding that ‘Marx problematised the ecological crisis not from the standpoint of capital, but rather from the perspective of free and sustainable human development’ (8). That is, Marx went beyond anti-capitalism to oppose all forms of further economic development.

The first problem with Saito’s argument is that it rests heavily on his review of Marx’s post-1868 notebooks. It is very dangerous to rely on anyone’s notes to determine what he or she thinks. That’s because taking notes on other people’s writings does not signify endorsement of their views. Looking at his notes alone, it would be near impossible to distinguish agreement from disagreement.

Marx’s notebooks for his critique of political economy are a case in point. In his preparations for writing Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Marx took notes on many texts from classical political economists, like Adam Smith, David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill. If one reads these notes without the benefit of reading Capital, it is difficult to work out what he actually thought of the passages noted down. It is only because they formed the basis for the developed and published critique of Capital that we can understand his thinking in the notebooks.

And that is the problem with the post-1868 natural-science notebooks. They did not form the basis for an actual published work. There is no ‘critique of political ecology’ by Marx. And, as a result, there is no way of determining his thought on ecology from these notes. To draw on Marx’s descriptions of some of capitalism’s destructive impacts – on man, society or nature – as evidence that he was anti-development ignores the extent to which Marx frequently praised capitalism precisely for its development of humanity’s productive forces. The claim that Marx was a pioneering degrowth ecologist is without foundation.

The myth of the ‘metabolic rift’

The second problem lies in the claim that Marx’s ecological concerns derived from his ‘theories’ of ‘metabolism’ and of ‘metabolic rift’. This rift supposedly refers to the separation of humanity from nature induced by class society and capitalism. Saito argues these components of Marx’s thinking were ‘suppressed’ by later Marxists. This led to the ‘marginalisation’ of Marxian ecology until its rediscovery at the end of the 20th century by the likes of Burkett and Foster (9).

Now it is true that some English translations of the original German edition of Capital include the word ‘metabolism’. It is also true that it can refer to man’s ‘metabolic’ relationship with nature. But it is a huge leap for these leftists to assert that usage of this particular word makes Marx an environmentalist.

Take its usage at the end of the lengthy and mostly historical Chapter 15 in Capital: Volume I. Entitled ‘Machinery and Modern Industry’, this chapter describes the impact of industry and mechanisation on agriculture. In one passage, Marx refers to man’s material interaction with the soil. In the original German, it reads ‘stört sie andererseits den Stoffwechsel zwischen Mensch und Erde’. This can be translated as ‘[capitalist production] disturbs the metabolism between humans and the earth’.

In the 1976 Penguin edition, it reads as: ‘it disturbs the metabolic interaction between man and the earth’. In the first English edition in 1887, translated by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling and edited by Friedrich Engels, the same sentence is translated as: ‘it disturbs the circulation of matter between man and the soil’.

Marx immediately continues his explanation:

‘That is, [capitalist production] prevents the return to the soil of its constituent elements consumed by man in the form of food and clothing; hence it hinders the operation of the eternal natural condition for the lasting fertility of the soil… Capitalist production, therefore, develops technology, and the combining together of various processes into a social whole, only by sapping the original sources of all wealth – the soil and the labourer.’ (10)

Whichever translation we use, Marx seems to be describing how the process by which human waste used to be returned to replenish the soil is being restricted because many more people now live in cities, away from rural areas. There is little doubt that Marx is here describing how the developed form of capitalist agriculture can be detrimental to the fertility of the soil.

But Marx uses the same word ‘metabolism’, or Stoffwechsel, more widely in his writings and in sections that have nothing to do with the interaction between man and nature. It usually refers to one of Marx’s key concepts: the interchange of forms. This could mean the interchange of commodity and money, or the interchange of different products. For instance, in chapter three of Capital: Volume I, on money as a means of payment, Marx explains that money does not serve ‘as a mere transient agent in the interchange [des Stoffwechsels] of products, but as the individual incarnation of social labour, as the independent form of existence of exchange-value, as the universal commodity’. (11)

There are other mentions of ‘metabolism’ in Capital which also relate to nature. But these have very different implications to those drawn by his eco-Marxist re-interpreters. For instance, in a long paragraph towards the end of Capital: Volume III, Marx discusses the capitalist process of production as a ‘historically determined form’ of the social process of production. He uses the word Stoffwechsel to describe how in the production process, labouring man makes use of the material elements of nature.

Here Marx is explaining why a surplus-product derived from surplus-labour is required in all types of societies, both as ‘insurance against accidents’ and also for the ‘necessary and progressive expansion of the process of reproduction in keeping with the development of the needs and the growth of population’. The same paragraph continues by extolling the benefits of increased labour productivity. Productivity improvements can ‘in a higher form of society’ (by which he means socialism or communism) combine the production of surplus-labour with a greater reduction in labour time devoted to material production. The implication is plain that productivity, and therefore, growth would be greater in post-capitalist societies. He is arguing for the very opposite of degrowth.

In the same paragraph, Marx makes a significant point about freedom. It is worth reading at length given radical environmentalist efforts to paint Marx as an opponent of growth and consumption:

‘In fact, the realm of freedom actually begins only where labour which is determined by necessity and mundane considerations ceases; thus in the very nature of things it lies beyond the sphere of actual material production. Just as the savage must wrestle with nature to satisfy his wants, to maintain and reproduce life, so must civilised man, and he must do so in all social formations and under all possible modes of production. With his development this realm of physical necessity expands as a result of his wants; but, at the same time, the forces of production which satisfy these wants also increase. Freedom in this field can only consist in socialised man, the associated producers, rationally regulating their interchange [Stoffwechsel] with nature, bringing it under their common control, instead of being ruled by it as by the blind forces of nature; and achieving this with the least expenditure of energy and under conditions most favourable to, and worthy of, their human nature. But it nonetheless still remains a realm of necessity. Beyond it begins that development of human energy which is an end in itself, the true realm of freedom, which, however, can blossom forth only with this realm of necessity as its basis. The shortening of the working-day is its basic prerequisite.’ (My emphasis) (12)

In the original German ‘rationally regulating their interchange with nature’ reads ‘diesen ihren Stoffwechsel mit der Natur rationell regeln’, which could also be translated as ‘rationally regulate their metabolism with nature’. Whichever translation is used, this paragraph shows just how misleading it is to use Marx’s deployment of the word Stoffwechsel to imply that he had a theory of metabolism that was concerned with the harms of economic growth. Rather, Marx supported productivity growth because it delivered social, human benefits.

This shouldn’t be a surprise. Far from rejecting Enlightenment thinking about man’s dominion over nature, as degrowthers claim, Marx embraced it. As the paragraph above shows, he thought humanity should use reason to overcome nature’s constraints on man’s freedom.

There is clear continuity here with Marx’s thinking in the Grundrisse – his notebooks of preparatory research for Capital written in the late 1850s. Here Marx wrote approvingly of the post-capitalist possibilities of the ‘full development of human mastery over the forces of nature, those of so-called nature as well as of humanity’s own nature’ (13).

This ‘post-capitalist vision’ seems quite consistent with the conventional reading of Marx as an heir of the Enlightenment tradition, but whose thought, in many ways, transcended it. He championed an energy-efficient, nature-dominating mode of production, that achieves much higher levels of productivity (output per person) – not as an end in itself, but as a means to establish the ‘true realm of freedom’.

Marx was not green

Nevertheless, Foster for one claims that ‘Marx not only regarded the “metabolic rifts” under capitalism as the inevitable consequence of the fatal distortion in the relationship between humans and nature but also highlighted the need for a qualitative transformation in social production in order to repair the deep chasm in the universal metabolism of nature’. Foster and others claim that ‘ecology’ and the theory of ‘metabolic rift’ are an ‘integral part of Marx’s critique of political economy’ (14).

Yet there are no mentions at all of these supposedly integral terms – ‘ecology’ and ‘metabolic rift’ – in any of the three volumes of Capital in English or in German. Even Saito is forced to admit that it’s ‘unfortunate’ Marx did not ‘elaborate on the concept of “metabolic rift” in detail in Capital’ (15). Saito is being disingenuous. Marx did not mention the ‘metabolic rift’ in Capital at all.

The single reference Saito provides for Marx’s supposed warning about the dangers caused by the metabolic rift, is to Capital: Volume III. There Marx uses the phrase ‘irreparable rift’, in Chapter 47 on the ‘Genesis of Capitalist Ground-Rent’. It turns out that the eco-Marxists’ claim that Marx was a modern environmentalist depends a great deal on their reading of a single paragraph in a single chapter.

So, in the original publication of Capital: Volume III in 1894 (a decade after Marx’s death), he described how a smaller agricultural population and a larger urban industrial population ‘creates conditions that provoke an irreparable rift in the interdependent process of social metabolism, a metabolism prescribed by the natural laws of life itself. The result of this is a squandering of the vitality of the soil, which is carried by trade far beyond the bounds of a single country. (Liebig).’ (My emphasis) (16).

Once again, Marx is referring to how faster urbanisation under the conditions of capitalist industrialisation has led to the declining usage of human waste to fertilise the land. This, as stated above, saps the soil’s ability to replenish its nutrients. Marx is here explaining how the changing form of land ownership, and the expansion of urbanisation that accompanies capitalist development, can accelerate farming’s exhaustion of the soil’s fertility.

Saito goes back to Marx’s manuscript for an earlier version of the passage. He suggests that Engels ‘intentionally changed’ this passage prior to publication and blurred its ecological message. In Marx’s own draft, he described the ‘conditions that provoke an irreparable rift in the interdependent process between social metabolism and natural metabolism prescribed by the natural laws of the soil’ (17). It appears that during his editing of Marx’s manuscript, Engels omitted the phrase ‘natural metabolism’, and changed the word ‘soil’ to ‘life’.

We will probably never know why Engels made this modification and whether it was intentional or accidental. I happen to agree with Saito that the earlier draft makes Marx’s meaning clearer. But whichever version is used, Marx’s thinking is the same. He is describing how capitalist social relations can interfere with previous practices that used human excrement to help replenish the soil. But to extrapolate from this idea, which Marx himself takes from German chemist Justus von Liebig, and claim that Marx was expressing even an embryonic belief in capitalism’s inevitable tendency to destroy the planet is more than a little absurd.

Unfazed, Saito insists on blaming the absence of actual ecological thinking in Marx’s published writings on the unfinished nature of Capital and the editorial role of Engels. He claims that Engels, though an honest person, lacked the intellect to ‘understand Marx’s intentions and to reflect them in his edition of Capital’ (18). As a result, he helped make Marx’s ecology ‘invisible’.

It is well known that the second and third volumes of Capital were only published by Engels after Marx’s death. If only Marx had the time and opportunity, Saito claims, he would have revised all three volumes to incorporate his environmentalist degrowth ideas – ideas developed by Marx later in life, when he began to study natural sciences.

Saito claims Marx only began this new research into the natural sciences after completing the first volume of Capital in 1867. Because he barely published after 1867, we only have ‘notebooks consisting of various excerpts and comments relating to environmental issues’, Saito argues (19).

There are some telling discrepancies in the timeline of this story. First, Saito, Foster and others claim that Marx developed his modern ecological insights in response to Liebig’s Organic Chemistry in its Application to Agriculture and Physiology, published in 1862. And they claim that Marx only began his natural-science studies after publishing the first volume of Capital. Yet Marx openly references this Liebig text five times in Capital: Volume I. Moreover, Marx drew on Liebig’s 1842 edition of Organic Chemistry for the Grundrisse, too. This further confirms that Marx’s interest in the natural sciences was not, as Saito initially suggested, a post-1867 departure. If Marx’s reading of Liebig was as influential in his ecological awakening as the eco-Marxists claim, then why didn’t he write about such an important ‘discovery’ in Capital: Volume I?

Furthermore, it is simply not true that we don’t get to see the ecological dimension in Marx’s work because he barely published work after 1868. Marx published plenty after 1868. In addition to myriad articles and reports, these post-1868 works include ‘The Civil War in France’, written and published in 1871, and the ‘Nationalisation of the Land’, an article written and published in 1872. Marx also revised the second German edition of Capital: Volume I, published in 1873, and wrote a substantial afterword to it, too.

Then there’s Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Programme, written in 1875 and published in 1890. Once again, Marx gave no indication of any new appreciation of the importance of environmentalism. In the Critique, he wrote:

‘Nature is just as much the source of use values (and it is surely of such that material wealth consists!) as labour… And insofar as man from the beginning behaves toward nature, the primary source of all instruments and subjects of labour, as an owner, treats her as belonging to him, his labour becomes the source of use values, therefore also of wealth.’

These words were written well after Marx had supposedly turned into a degrowth environmentalist. Yet here he is, continuing to articulate an Enlightenment vision of nature as man’s object to use.

If Marx had really undergone an ecological awakening in the late 1860s – ‘immediately after the publication of Volume I’ in 1867, as Saito has it – it is hard to believe that he wouldn’t have mentioned it at some point. And if, as Saito confusingly claims elsewhere, Marx had actually undergone an environmentalist awakening prior to 1867, then why is there no trace of it in Capital: Volume I? The more one studies Marx, the more absurd the claims are for him being any sort of environmentalist at all.

To put it bluntly, nobody has yet discovered in Marx’s completed works anything like a belief in a capitalist tendency towards environmental emergency. Marx did not think there were natural limits to growth. And he never once urged humanity to exercise productive restraint. To think otherwise is a product of eco-Marxists’ tendency to project their concerns backwards through history.

The folly of ‘reconstructing’ Marx

Contemporary Marxists are free to propound some vision of ‘eco-socialism’, or to dream of some red-green alliance should they wish to do so. The problem is that they try to do so by tendentiously ‘reconstructing’ Marx in ways that cut against the very grain of his thought.

They claim that Marx thought that transcending the capitalist mode of production would mean much more than the re-appropriation of the means of production by the working class. Instead, it would result in the disappearance of the productive forces of capital and the necessary cessation of the ‘ecologically destructive forms of production’. ‘In other words’, Saito writes, ‘even if the “fetter” of the development of productive forces is overcome through the transcendence of the capitalist mode of production, capitalist technologies remain unsustainable and destructive and cannot be employed in socialism’ (20).

Here, Saito is re-interpreting Marx’s conception of the ‘self-destructive’ tendencies of capitalism as a reference to the destruction of the natural environment. Yet that isn’t what Marx meant at all.

In the Grundrisse, Marx argued that capitalism’s tendency towards crisis arises from the tendency for the rate of profit to decline. Describing this ‘as the most important law from the historical viewpoint’, he explained how capitalist social relations become ‘a barrier for the development of the productive powers of labour’. The ‘self-destruction’ Marx is writing about, is the self-destruction of capitalism as a social system, not the destruction of the planet. As Marx himself put it, ‘the violent destruction of capital not by relations external to it, but rather as a condition of its self-preservation, is the most striking form in which advice is given it to be gone and to give room to a higher state of social production’ (21).

Or as Marx put it in a much-quoted passage from Capital: Volume I:

‘The monopoly of capital becomes a fetter upon the mode of production, which has sprung up and flourished along with, and under it. Centralisation of the means of production and socialisation of labour at last reach a point where they become incompatible with their capitalist integument. This integument is burst asunder. The knell of capitalist private property sounds. The expropriators are expropriated.’

There is no sign here of Marx rejecting taking control of the capitalist means of production because of modern technology’s environmental destructiveness. Instead, he explicitly looks forward to the expropriation by the masses of capitalistic private property and its means of production.

The likes of Saito can creatively ‘reconstruct’ or ‘reinterpret’ Marx in order to ‘update’ the contents of Capital. They can repeat the word ‘metabolic’, and insert the adjective ‘ecological’ as many times as they want. They can make multiple claims about the ‘metabolic rift’. But nothing in Marx’s actual published works reveals, or even suggests, a theory of ecology that asserts that productive development is degrading nature to the point of human extinction.

It is an extraordinary leap of imagination to claim that Marx thought that humankind’s dominion over nature heralded the destruction of the Earth. Never mind that he proposed ‘degrowth’ as the solution. In fact, Marx staunchly opposed the proto-green, counter-Enlightenment forces of his own time.

Were he alive today, he would be firmly standing up to today’s reactionary environmentalists and the backward ideology of degrowth.

Phil Mullan’s Beyond Confrontation: Globalists, Nationalists and Their Discontents is published by Emerald Publishing. Order it from Amazon (UK).

(1) The Future is Degrowth: A Guide to a World Beyond Capitalism, Michael Schmelzer et al, Verso, 2022, p35

(2) The Future is Degrowth: A Guide to a World Beyond Capitalism, Michael Schmelzer et al, Verso, 2022, p39

(3) The Future is Degrowth: A Guide to a World Beyond Capitalism, Michael Schmelzer et al, Verso, 2022, p142

(4) Marx in the Anthropocene, Kohei Saito, Cambridge University Press, 2023, p15

(5) Marx in the Anthropocene, Kohei Saito, Cambridge University Press, 2023, p249

(6) Marx in the Anthropocene, Kohei Saito, Cambridge University Press, 2023, p158

(7) Marx in the Anthropocene, Kohei Saito, Cambridge University Press, 2023, p173

(8) Marx in the Anthropocene, Kohei Saito, Cambridge University Press, p128

(9) Marx in the Anthropocene, Kohei Saito, Cambridge University Press, p14

(10) Capital: Volume I, Karl Marx, Lawrence & Wishart, 1974, pp474-475

(11) Capital: Volume I, Karl Marx, Lawrence & Wishart, 1974, p137; Original German 1867 edition, p99

(12) Capital: Volume III, Karl Marx, Lawrence & Wishart, 1974, p820

(13) Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy, Karl Marx, Penguin, 1993, p488

(14) Marx in the Anthropocene, Kohei Saito, Cambridge University Press, p15

(15) Marx in the Anthropocene, Kohei Saito, Cambridge University Press, p23

(16) Capital: Volume III, Karl Marx, Penguin, 1981

(17) Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA) II/4.2 M, pp752-753

(18) Marx in the Anthropocene, Kohei Saito, Cambridge University Press, pp51-52

(19) Marx in the Anthropocene, Kohei Saito, Cambridge University Press, p16

(20) Marx in the Anthropocene, Kohei Saito, Cambridge University Press, pp155-158

(21) Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy, Karl Marx, Penguin, 1973, pp748-750

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.