Beware politicians posing as paragons of ‘decency’

Words like kindness, compassion and inclusivity are a form of linguistic blackmail against would-be dissenters.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

One of the most devious words in political discourse today is ‘decency’. It’s everywhere at the moment.

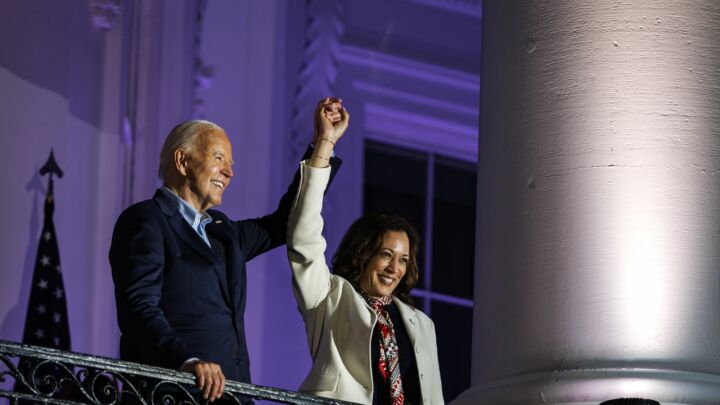

Last Thursday, Oprah Winfrey issued a direct appeal to unaffiliated and undecided voters to back Kamala Harris as the next US president. ‘Decency and respect are on the ballot in 2024’, she said, ‘character and values most of all’.

The same word was employed by Max Hastings earlier this month. Writing in The Times, he concluded that the Democrats were the party all Americans should back, as they embody ‘fundamental decency and moderation’. The same day, Alan Rusbridger, in his Prospect column, inveighing against Elon Musk’s X, wished there was a ‘reliable, decent, honest, well-tended [social-media] platform that can never be taken over by a billionaire man-child’.

Decency is a vague, asinine word. It’s beloved of people who seem to think that being a nice person and having good manners are the same as having good politics – the kind of people who deprecate Donald Trump for his coarseness and vulgarity, and who revile Musk’s X for allowing users to express horrid, ‘hateful’ words. ‘Decency’ is an empty mantra for a class that likes its politics bland and consensual.

This is why you should beware the appeals to decency. It’s used by people who want to shut others up, who would be happy to see X hobbled and GB News taken off the air. They conflate being offensive, impolite and airing unfashionable and brash opinions with inciting actual hatred and violence. ‘Decency’ is a form of attempted linguistic blackmail, designed to make dissenters feel the opposite: indecent, uncivilised and abnormal. It belongs in the same category as that other insipid mot du jour, ‘grown-up’ (the antithesis of which is ‘childish’ or ‘juvenile’). Both sit alongside the better-established ‘kindness’ (anyone who disagrees is unkind), and that long-standing declaration of egotism deployed by the crafty and the naïve: ‘compassionate’.

This kind of linguistic trick, of using nice words to cajole others, is not only conniving, it’s often plainly dishonest. Sometimes nice words are not what they seem. Those ignorant of woke ideology may look at the word ‘equity’ and see it as obviously harmless. But it entails something more ambitious and sinister than mere equality: a desire to engineer society wholesale to achieve political ends. ‘Inclusion’ can often mean its precise opposite: excluding those with undesirable opinions. Most of us realised a while ago that the innocuous-sounding hashtag, #BeKind, carried a nasty, unspoken threat behind it.

Humanists UK currently carries the following manifesto on its X bio: ‘We advance free thinking and promote humanism to create a tolerant society where rational thinking and kindness prevail.’ I’m all for rational thinking and tolerance, but less keen on the specious platitudes about kindness. Seductive words like kindness, compassion and decency should be treated with high caution.

Woke is the enemy of the arts

A new Disney series, lauded and lambasted earlier this year as the ‘gayest’ Star Wars outing yet, has been cancelled. The Acolyte, the franchise spin-off about a matriarchal society devoid of male characters, featuring twin sisters born to a lesbian couple, was given the heave-ho earlier this month, after just one series. It was reasonably well-received by critics, but it divided fan opinion and its viewing figures dwindled after the opening episode in June.

This should hardly surprise us, given Disney’s recent disastrous dalliance with fashionable politics. In recent years, it has released Lightyear, a Toy Story spinoff replete with a lesbian kiss largely irrelevant to the plot, and a live-action Pinocchio, with a black Blue Fairy. As Laurie Wastell wrote on spiked two years ago, while woke critics love ‘message movies’, audiences by and large do not. They go to the cinema to be entertained, not lectured to. Marvel, too, has learnt the high price of riding the woke wave.

Woke is not just bad for business, it’s bad for art. When politics is placed ahead of performance, the latter usually suffers. The gender and racial quotas imposed by the Oscars last year will no doubt suffocate an industry that should be concentrating on delivering stories. In the UK, television drama and comedy have become largely unwatchable owing to hyper-tokenism. On the stage, painfully right-on Shakespeare productions have become a laughing stock – albeit an exorbitant and deeply unfunny one.

This was brought home to me when an older, Lib Dem-voting acquaintance, a passionate patron of the theatre since a boy, recently returned from the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. He was fuming at the sermon he had been subjected to in the guise of a play. And this was merely the latest of a long line of such similar instances.

The broadcaster, journalist, playwright and satirist Andrew Doyle mentioned some time ago on GB News that he generally avoids the theatre these days for this very reason. As he told me this week: ‘I only go now after careful research to make sure it’s not ideological nonsense. I cancelled my tickets to Macbeth at the RSC when the reviews made clear it was just agitprop.’

I wonder why other theatre-goers don’t do likewise. Many movie-aficionados already do.

Oasis were always retro

One of my proudest boasts back in the 1990s was that I was into Oasis well before anyone I knew was. As a 19-year-old indie kid, I bought the band’s debut single, ‘Supersonic’, in April 1994. I saw them perform live at the Manchester University Students’ Union in June that year. I even found myself drinking alongside Liam Gallagher in the Queen of Hearts pub in Fallowfield later that summer.

As someone also into classic 1960s rock, the retro sound of Oasis resonated with me. In retrospect, too closely. While ‘I Am the Walrus’ was already a set favourite on stage, ‘Cigarettes and Alcohol’ had a riff lifted straight from ‘Get It On’ by T Rex (1971), and ‘Shakermaker’ had a melody taken from ‘I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing (In Perfect Harmony)’ by the New Seekers (1973). ‘Rock’n’Roll Star’, the opening track of Oasis’ outstanding debut album, Definitely Maybe, was a declaration of intent. They wanted to be rock stars. Just like their idols.

‘Fans who miss the 1990s can stop crying their hearts out.’ So said a Times editorial on Wednesday. Yet it’s with some irony that we bask in retro glory as the band now get back together, 30 years this week after the release of Definitely Maybe. Oasis were retro even back then.

Mind you, with their cheeky-chappy, faux-cockney homage to the Small Faces, so were their arch-rivals, Blur.

Patrick West is a spiked columnist. His latest book, Get Over Yourself: Nietzsche For Our Times, is published by Societas.

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.