The Royal Society’s lockdown pseudoscience

This once venerable scientific institution has ignored all of the real-world evidence against the Covid restrictions.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Last week, the Royal Society of London published its report on the effectiveness of so-called Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) against the Covid pandemic. The press release, widely recycled in the papers, claims that measures like lockdowns and masks ‘unequivocally reduced Covid-19 infections’.

The report itself is rather more cautious than some of the media reporting suggests. As a systematic review of published data, it acknowledges that many studies of NPIs were observational and not based on controlled trials – something that would be demanded for assessing the effectiveness of a new vaccine or therapeutic. Nonetheless, the report concludes that bundles of measures – including masks, social distancing, public-information campaigns, contact-tracing and business closures – achieved some effect in reducing the spread of Covid. The report goes on to highlight Hong Kong, New Zealand and South Korea as exemplars of ‘successful’ NPI deployment.

The Royal Society’s motto, adopted from the 17th century, is ‘Nullius in verba’, meaning ‘take nobody’s word for it’. It is, the Royal Society explains, ‘an expression of the determination of fellows to withstand the domination of authority and to verify all statements by an appeal to facts determined by experiment’. Presumably, then, the Royal Society won’t mind if I kick the tires of its report.

Systematic reviews – which seek to consider all relevant literature – should aim to suppress their authors’ personal biases. They come a cropper, however, when publication bias is strong. This has especially been the case when it comes to the scientific literature around Covid. Sceptical authors have found it difficult to publish their results and analyses throughout the pandemic – whether it be on NPIs or the origins of Covid. This invariably determines what is published and therefore what literature the Royal Society report could review.

Even those high-quality studies that have been published, and that question the utility of NPIs, are glossed over by the Royal Society report. The January Cochrane Review, for example, found scant evidence of the benefits of masks in high-quality randomised-control trials. Cochrane Reviews are generally considered the gold standard of systematic reviews and yet its review on masking makes no appearance in the report.

Real-world evidence against NPIs is also nowhere to be found in the Royal Society’s report. Although only a minority of countries adopted few or no restrictions in response to the pandemic, Belarus, Sweden and Nicaragua can all be counted as examples. They are the closest to a control group that we have if we are truly to understand the effects of NPIs. However, searching the report for these countries returns zero hits. This is odd, considering that South Korea appears 52 times and China 19 times.

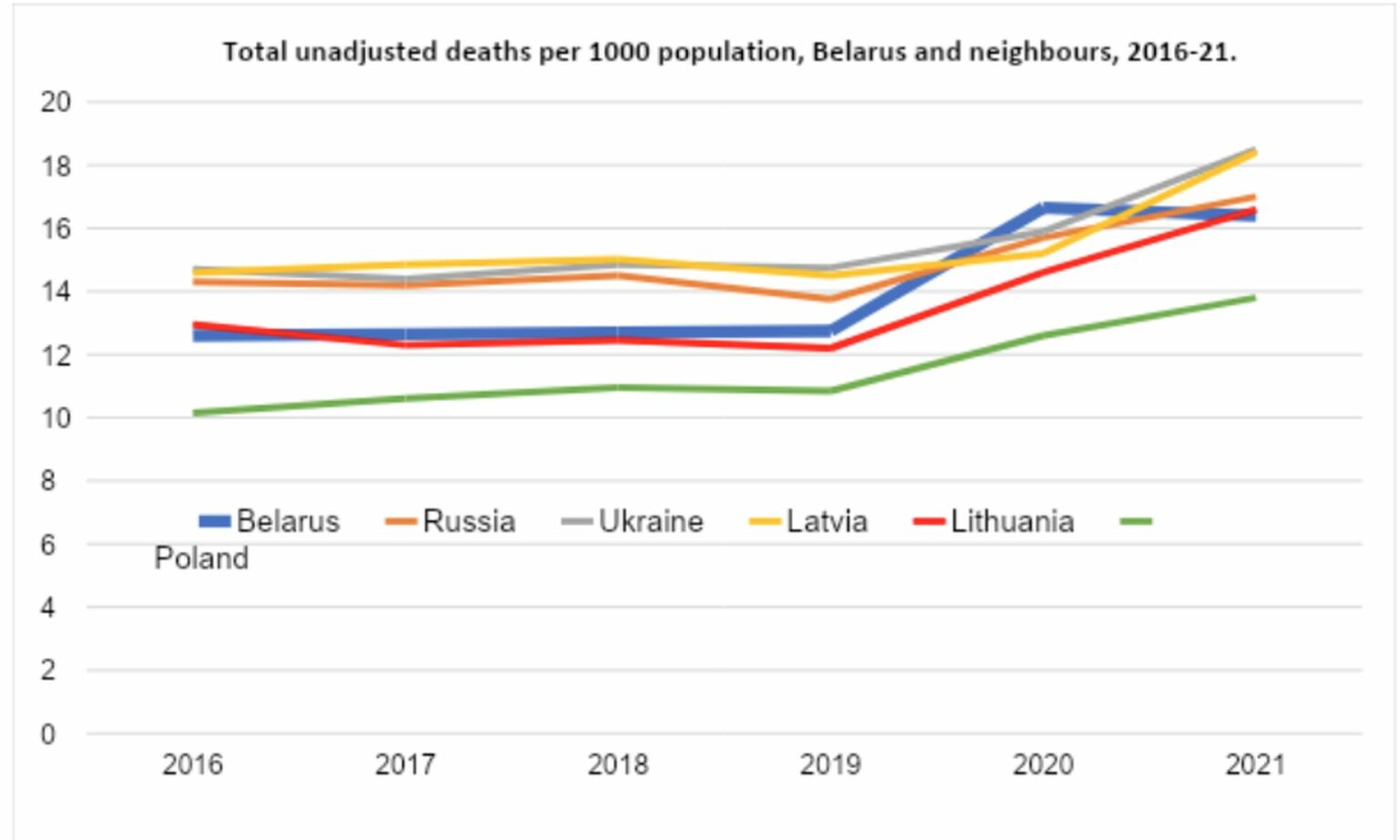

The evidence from Sweden, Nicaragua and Belarus is hard to refute. Using the World Bank’s mortality database for 2020 and 2021, we can compare these control countries with adjacent countries that imposed extensive NPIs. Reviewing total deaths is more accurate than counting ‘Covid deaths’ because this category is muddied by countries having different definitions of Covid deaths and different levels of testing.

Looking at the data, Belarus had a steeper rise in deaths in 2020. Yet by 2021, its neighbours had caught up or overtaken in terms of total deaths. It certainly didn’t have a disproportionately massive spike in deaths, despite imposing no restrictions at all.

The story is the same when we compare Nicaragua with Costa Rica to the south and Honduras to the north, where lockdown was enforced at gunpoint. As for Sweden, it initially experienced higher rates of excess mortality than neighbours Norway, Finland and Denmark. Now though, Sweden has around the lowest all-pandemic excess mortality for the entire continent.

The Royal Society report also contains no mention of US states that had fewer NPIs or that abandoned lockdown early, notably South Dakota and Florida. South Dakota provides a great case study insofar as it never had a mask mandate. Meanwhile North Dakota, with a similar population, imposed one in November 2020 when both states were experiencing huge Covid spikes. Infections then declined at a similar pace in both, suggesting that masking didn’t make much difference.

The situation was similar in Japan. Despite the report’s emphasis on South Korea’s ‘success’ – which involved the incredibly intrusive tracking of its citizens – it misses the fact that Japan achieved similar results without having any lockdowns and with no aggressive track-and-trace system in 2020 and 2021.

The report barely even touches on the considerable harms caused by invasive restrictions in places like South Korea and China, let alone in the UK. The Royal Society admits there were some negative consequences to shutting down society, and then brushes these aside, saying that this is for others to investigate. Really? This is the equivalent of a doctor curing a disease with an equally deadly treatment, and then deciding that it’s someone else’s problem.

The devastating consequences of lockdown deserve recognition. The UK’s government debt has vastly increased post-lockdown. Inflation has soared. Education has been wrecked. Excess deaths in England chug along at between 5,000 and 6,000 per month, with nobody in authority caring much at all. Currently most of these deaths are caused by heart and circulatory diseases. But given the extent to which cancer diagnoses were delayed and prevented during the height of lockdown, there is every grim likelihood that a wave of cancer deaths will follow.

Considering all this, can we really say that Covid measures were an ‘unequivocal’ success? Nullius in verba. Or, in plain English, ‘Don’t you believe it, mate’.

David Livermore is a retired professor of medical microbiology.

Picture by: Getty.

Celebrate 25 years of spiked!

A media ecosystem dominated by a handful of billionaire owners, bad actors spreading disinformation online and the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories. But we have you on our side. help to fund our journalism and those who choose All-access digital enjoy exclusive extras:

- Unlimited articles in our app and ad-free reading on all devices

- Exclusive newsletter and far fewer asks for support

- Full access to the Guardian Feast app

If you can, please support us on a monthly basis and make a big impact in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.